One of the marvelous outcomes of so many contemporary pro wrestlers penning autobiographies and indulging in shoot interviews is the opportunity for valuable recollections to be recorded. One of the unfortunate side effects is that those histories are often recorded incorrectly, embellished for effect, misremembered, or adulterated beyond recognition.

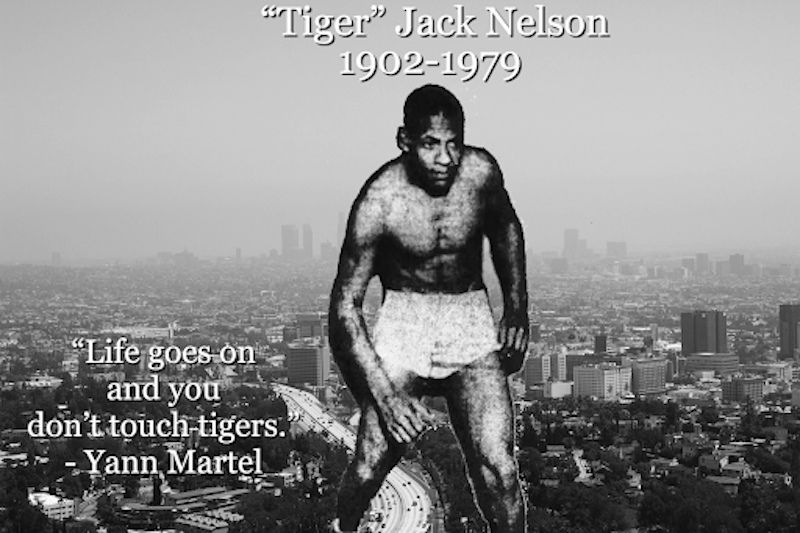

Roddy Piper’s 2002 autobiography In The Pit With Piper includes a collection of tales about Tiger Nelson, who Piper refers to as one of the greats from the past who was still lurking in the locker room of the Los Angeles Olympic Auditorium. Piper describes Nelson as about 108 in the late-1970s, which was an attempt at humor since Nelson was at most 77.

Piper then attributes a colorful series of stories to Nelson that he supposedly offered to Piper as the two shared a bottle of Ripple in the elder wrestler’s humble Watts abode. All of the stories are either plainly exaggerated, or misremembered in critical areas. At the conclusion of the tale, Piper states that he departed from Nelson while the latter was in a coughing fit on the bed of his small home, and that was the last time he saw Nelson alive. From there, Piper narrates that he was one of only four attendees at Nelson’s funeral, which was a military affair.

The final portion of the story is possibly true, as the death of Theodore Roosevelt Reed—known in combat circles as “Tiger” Jack Nelson—just happened to overlap with Piper’s one-week return to Los Angeles before he solidified his position as a permanent fixture in the Pacific Northwest. Reed passed away on January 8th, 1979, and was buried at Los Angeles National Cemetery on January 12th, which means Piper could’ve been present at Reed’s funeral if he completed the two-hour drive from Bakersfield to Los Angeles right after concluding his business with Tatsumi Fujinami for the WWWF Junior Heavyweight Championship.

Grave marker of Theodore Roosevelt Reed AKA “Tiger” Jack Nelson

The one critical element of Reed’s story that Piper got correct is that Tiger Nelson was a great wrestler by several definitions. He was one of the earliest holders of a Black world heavyweight championship backed by a title belt. Moreover, Nelson’s reign would spark imitation, and grant him a legacy among Black pro wrestlers that would extend beyond his unglamorous in-ring career. Though little’s known about Tiger Nelson’s upbringing, it’s evident he was born in Austin, Texas on March 3rd, 1902 as Theodore Roosevelt Reed, son of Lee Reed and Hattie Pettit.

The next time Reed pops up on the radar, he is already a professional wrestler going by the name of “Tiger” Jack Nelson, and operating as a rule-breaker in the wrestling rings of New York and Pennsylvania. He was apparently referred to as “Tiger Jack” to differentiate him from “Tiger” Bill Nelson, a white wrestler from St. Louis who was active in the same region during that exact period of time.

Already 30, Nelson was vilified in the October, 15th, 1932 edition of The Philadelphia Inquirer for “... doing as much punching as he did clawing” in his bout against Berto Asirati of Italy. Nelson’s illegal tactics that night earned him a disqualification loss. Later that month, a writer from The Camden Evening Courier described Nelson as being “a veteran who is as clean as the driven snow covered in coal dust.”

By 1934, Nelson had already achieved championship status of a sort, at least with respect to the way he was promoted publicly. In the run-up to a high-profile encounter between Jim Londos and Jim Browning in June of that year, Nelson’s identified as one of three wrestlers that Browning was training with to prepare for his bout with Londos. The writer describes Nelson as “the acknowledged Negro champion of America.”

From there, Nelson reemerged in California during the summer of 1935, hailed as “a colored wrestler who is touted as one of the most colorful and action performers in the mat game” by The San Bernardino County Sun.

Within his first month of wrestling along the California coast, Nelson’s act drew rave reviews even though he always left the ring in defeat. Upon learning that Nelson would be facing Hugh Claphan in an upcoming bout, Carl Johnson of The Bloomington News praised Nelson’s overall presentation, if not his technical prowess.

“The match I shan’t miss is the opener between ‘Tiger’ Nelson and Hugh Claphan,” wrote Johnson. “I have never seen Claphan, but I have seen the ‘Tiger.’ As a hair-pulling, riot-causing nut, he is tops. As a wrestler, he isn’t much, but he is fun to watch.”

True to form, Nelson lost his bout with Claphan in short order, but he accomplished just enough to be remembered. As the writer from The San Bernardino County Sun recounted, “Jack ‘Tiger’ Nelson proved a strong attraction despite his defeat by Hugo Claphan, the strong Canadian. Nelson proved to be a flashy and speedy grappler, and at times had Claphan in a bad way, but lost the scheduled 30-minute joust in less than six minutes as the result of a body press.”

As was a common practice with American-born Black wrestlers, the ascent of Haile Selassie to the position of Emperor of Ethiopia in the 1930s resulted in many of their number being labeled as Ethiopian to exoticize them. Nelson was declared to be of Ethiopian extraction in several news reports. It was a strategy that would later be applied to the ring name of George Hardison, who’d achieve fame as Seelie Samara. At least Nelson was able to retain his original ring name.

The story of Nelson’s supposed international origin was neither applied consistently nor ubiquitously, and Nelson’s point of origin would vacillate between Ethiopia and Harlem depending on who was handling the promotion. He was either called “the Ethiopian mat wonder” as written in The San Luis Obispo Tribune, or “the colored boy from Harlem in New York” as described in The Hanfield Sentinel. Apparently in some parts of California, being a Harlemite was exotic enough.

Courtesy of The Salt Lake Tribune

For as much ink and attention as Tiger Nelson’s activities garnered, seemingly none of his matches materialized in victories, and he was only occasionally able to obtain draws under flukish conditions. An example of this is when Nelson cleanly lost the first fall of his Hanford match to Phil Guber via airplane spin, only for Hanford to twist his ankle on the outside of the ring, get counted out, and be unable to continue the contest.

The Salt Lake Tribune provided Nelson with his first semblance of a fleshed-out backstory when he made his debut there in March of 1936. It was explained that Nelson had acquired the “colored championship” of the National Wrestling Association—the adjacent wrestling body of the National Boxing Association—during a 1929 contest in New York City. The Tribune also confirmed Nelson’s role in training Jim Browning for his 1934 match with Londos, and listed Nelson’s point of origin as Seminole, Oklahoma, which was far closer to his real place of birth in Austin, Texas than any points of origin that publications had ever previously offered.

The Tribune also provided Nelson with a signature hold: The Flying Wristlock. The inclusion of this detail is curious inasmuch as Nelson hadn’t yet been granted a victory in any of his West Coast matches. He wouldn’t be victorious on this occasion, either. Although he locked Del Kunkel in his patented wristlock to secure the first fall, Nelson immediately surrendered the following two falls via bodyslam and piledriver.

While Nelson was the loser of the bout, The Tribune’s reporter did credit him with looking and moving very differently than most heavyweight wrestlers. “Unlike most heavyweights, Nelson is neither bulky, nor ponderous,” stated the writer, identified by his initials as J.C. D. “Contrariwise, he is lanky and exceptionally agile.”

As the year progressed, Nelson acquired fewer draws, and was allowed to tally losses in a more dignified manner, often by way of disqualification. He acquired an additional nickname in Provo, Utah ahead of his match with Leo Papiano—“The Black Panther” Tiger Nelson. It was a curiously redundant name, and The Daily Herald made note of it, declaring, “It is not clearly known which of these two animals, the panther or the tiger, that Nelson resembles most, but if it is a cross between them, then Papiano is a marked man.”

Through May of 1936, Nelson was still a “colored world champion” who was winless against White opponents, and the press took note of it while pointing out a quality in Nelson’s performances that contemporary wrestling reviewers would define as “workrate.” As The Deseret News pointed out, “Nelson has been scuffling around here most all season to the horrification of the ringsiders. He usually loses, but he makes a great show of it.”

Nelson finally rose above the level of lovable loser early in June of 1936 in Caspar, Wyoming when he pinned Lou Mueller in a best-of-three-falls affair. Stating that Nelson had “... lived up to his reputation as The Black Panther,” The Caspar Star-Tribune described how Nelson had finally secured a legitimate double-pinfall victory over a White wrestler for the first time in his career.

Two months later, Nelson secured a second multi-fall victory in Caspar, downing Jimmy Smith with a Boston Crab and a flurry of punches and kicks. He then achieved his first pinfall victories in front of California crowds one week later in early September when he pinned Bernie Spiel in Pasadena, and Roughhouse Burney in Bakersfield.

Then something bizarre happened in February of 1937. Someone going by the name of “Tiger” Jack Nelson arrived in Helena, Montana and wrestled like a technical marvel. According to The Independent Record, this powerful version of Tiger Nelson defeated Klem Kusek in consecutive falls following a “pinwheel slam” and “a complete reverse somersault.”

Seeking to capitalize on Nelson’s popularity, the promoters in Montana had acquired the services of a light-skinned wrestler from Ohio—LeRoy Howard Clayton—to play the role of Nelson. When it became clear that the phony Tiger Nelson was wider, younger, and five inches shorter than the real McCoy, the story was placed in The Independent Record that “Tiger” Jack Nelson also wrestled under the name “King Kong” Clayton.

Promotional Photo of World’s Colored Heavyweight Champion Jack Nelson

After being referred to by awkward portmanteaus like “Tiger King Kong” for a short time, Clayton permanently assumed the name “King Kong” Clayton. Back in California, the real Tiger Nelson was now carrying around a gold-and-diamond belt that was meant to represent the National Wrestling Association World’s Colored Heavyweight Championship that he’d allegedly captured in New York several years prior.

No matter how beautiful his championship bauble may have been, Nelson was afforded few if any opportunities to defend the belt; it was a trinket that helped to communicate to fans that he was a high-level enhancement talent. Still, his performances remained so entertaining that Warren Vinston of The California Eagle wrote in March of 1938 that he believed Nelson to be formidable despite the fact that he’d lost exponentially more matches than he’d won.

“The Tiger is recognized as the world’s colored heavyweight champion,” wrote Vinston. “If Nelson was given the opportunity, he has the stuff to take the racial identity from the title.”

Ironically, the only clear-cut defense of Nelson’s world title on record is his match against “The Black Panther” George Godfrey in 1939, which also appears to have been Nelson’s retirement match. The 6’3”, 255-pound Godfrey was one of three Black boxers, including Jack Johnson and Harry Wills, to popularize the name “The Black Panther.” The name became overused to such an extent that nearly every major Black wrestler of the era—including Nelson—was saddled with it at one point or another.

Like the other boxing panthers, Godfrey was extremely successful, and was a multi-time holder of the semi-official world colored heavyweight boxing championship. The bout with Nelson was advertised as Godfrey’s opportunity to add a world wrestling title of equivalent value to his resume. The outcome of the match hasn’t been reported, but Godfrey wasn’t declared a claimant to the world colored wrestling throne in California subsequent to his match with Nelson.

At that point, the in-ring career of Tiger Nelson was over, but he remained active on the Los Angeles wrestling scene. In 1940, Nelson was revealed as the trainer of wrestler Don Blackmon, and the reporter of the article credited Nelson with a 12-year uninterrupted reign as the colored world titleholder, which would’ve pushed back the date of Nelson originally capturing the title by a further two years to 1927 if it were true.

When U.S. involvement in World War II kicked off, Nelson enlisted in the U.S. Army, and participated in all-Army boxing showcases around California. This included at least one show at the Santa Maria Air Base in 1943 where Nelson was listed as a highlight participant alongside former world heavyweight boxing champion Max Baer, and the former champion’s brother Buddy Baer.

Theodore “Tiger Nelson” Reed’s World War II Draft Card

In 1944, Nelson was able to return to ringside long enough to appear as the manager to Seelie Samara during a bout in Los Angeles. Once the war was over, and extending into the 1950s, he made frequent appearances as a manager to a few wrestlers, most notably former gridiron star Woody Strode during the period before Strode made it big in Hollywood.

By the mid-1950s, Nelson appeared fully settled into his primary role as a masseur both inside and outside of the ring, as he listed his lone profession to be masseur when he offered an interview about high automobile registration fees to The Los Angeles Mirror in 1953.

The career of Nelson likely would’ve faded even further into obscurity during that time were it not for Black mat superstar “Gentleman” Jack Claybourne. In late-1948, nearly a decade after Nelson’s retirement from wrestling, Claybourne introduced himself to the Hawaii press as the New York State Athletic Commission Negro World Heavyweight Champion. While Claybourne was advertised internationally under similar titles, this time he brought along a diamond-studded championship belt with two names on it: Tiger Nelson and Rufus Jones.

Claybourne claimed the NYSAC Negro championship was first captured by Nelson in a tournament in New York City in 1941. Nelson had already retired from wrestling and was nowhere near New York in 1941. Whether it was for the sake of establishing credibility for his new world title, or because he desired to pay tribute to a forgotten Black wrestling legend, or both, Claybourne linked his personal championship to the lengthy and nearly defenseless world title reign of Tiger Nelson.

In subsequent interviews, Claybourne continued to tell the fictitious tale of how he came to be in possession of the NYSAC title, and how Nelson was the first wrestler to acquire that distinction. Nelson retroactively became the first holder of a world championship that would be defended in Hawaii, along with both coasts of the United States, and internationally in Australia and New Zealand.

The fact that the NYSAC never sanctioned a negro wrestling world championship, and likely punished Claybourne in 1954 for linking it to their organization, is beside the point. A decade after his retirement, Nelson’s name achieved a level of prestige in several regions of the globe that eluded him during his wrestling career.

Although his name traveled far and wide for six years—right up until Claybourne’s claims as a world titlist were more than likely silenced due to an early act of censure by the National Wrestling Alliance—Nelson largely faded into obscurity aside from his appearances as a fixture in the locker room of the Grand Olympic Auditorium.

This brings us to the question of what Piper actually saw in Nelson’s domicile, and the accuracy of the statements Piper attributes to Nelson, which may have been exaggerated by Nelson, misremembered or embellished by Piper, or both. Regarding Piper’s story that Nelson supposedly went 15 rounds in a boxing match with Jack Johnson—a bout that ended his combat sports career—that match certainly never happened. One explanation is that Piper saw a photo of Nelson in the ring with George Godfrey during his de facto retirement match, also heard a story of Nelson absorbing damage during an Army-hosted boxing match, and merged those events together in his mind.

As far as Nelson’s photo with Bob Hope is concerned, it’s highly unlikely that the photo was taken at a nightclub that Nelson once owned, and where Hope used to be employed. It’s more likely that the photo was taken during one of the famous entertainer’s many charitable interactions with troops in the Los Angeles area during World War II. As Nelson was participating in U.S. Army boxing events during that time, and Hope was a proud former boxer in his own right, it makes sense that the pair had opportunities to cross paths during wartime.

In a way, it’s fitting that Piper’s autobiography more than likely inflated Nelson’s post-career accomplishments to an unnecessary degree, just as Claybourne’s act of well-meaning commemoration had done the same five decades prior. The truth behind the life of Tiger Nelson was more than sufficient to tell the tale of a man who was clearly memorable to anyone who encountered him. He was a man who inspired the birth of the first Black world title that could cross boundaries because of all the boundaries he broke in his own life when provided with the opportunity.