In 1956, there was a major release of professional wrestling trading cards by Parkhurst Products. In a 121-card set consisting of wrestling luminaries as Lou Thesz, Bronco Nagruski and Verne Gagne, only four Black wrestlers were included: Jack Claybourne, Bobo Brazil, Bearcat Wright, and Luther Lindsay. On the back of Jack Claybourne’s card, it stated that he “... is regarded as the greatest colored wrestler of all time.”

Four years after this praise was heaped upon Claybourne as he sat amongst prestigious company, The California Eagle gave a grim retelling of the final afternoon of the wrestler’s life. The 49-year-old legend had reportedly received a communique that sealed his professional fate. Claybourne wouldn’t be invited on a wrestling tour of Europe—a tour that he’d apparently deemed to have been the last viable lifeline capable of jumpstarting his flagging career.

When Claybourne was found lying lifeless on the bathroom floor of his Los Angeles home on January 7th, 1960, it wasn’t a surprise to many of his closest friends. Apparently, he’d told anyone who’d listen that he’d take his own life if he wasn’t given an opportunity to extend a wrestling career that had lasted nearly 30 years. Claybourne’s threat of suicide wasn’t idle. Sometime after arguing with his adopted daughter and then calling his wife Lillian at work to inform her of the altercation, Claybourne loaded a 12-gauge shotgun, pressed the working end of the weapon against his head, and pulled the trigger.

The Los Angeles County coroner would encapsulate the ghastliness of the scene by summarizing Claybourne’s cause of death as such: “Shotgun wound of head with multiple skull fractures and almost complete evisceration of the brain.”

Thus ended the life of a man who’s been synonymous with the term “world champion,” even if his quest to be recognized as such may have hastened the termination of his career, and his life.

The idea of being labeled as a world champion was something Claybourne had plenty of time to grow accustomed to. At 22, the 180-pound Missouri native appeared on wrestling cards in Kansas billed as a holder of the Negro world light-heavyweight championship essentially upon his debut in the wrestling business. As he made his early rounds through various wrestling territories, Claybourne was varyingly labeled as a native of either Alabama or Minnesota in the newspapers, despite the fact that he was from Mexico, Missouri, a small town in the heart of state’s “Little Dixie” region. His birth name was simply Elmer Claybourne, the third of four children born to James and Ella Claybourne.

Jack Claybourne’s World War II Draft Card

As Claybourne traveled, he picked up additional nicknames that betray how closely the naming conventions of Black wrestlers followed the patterns of Black boxers from the same era. As early as 1935, when he was wrestling in El Paso, Texas and Juarez, Mexico, Claybourne was billed as “The Black Panther.” It was a name made most famous in boxing circles by World Colored Heavyweight Champion Harry Wills, and would result in a proliferation of Black Panthers in the world of wrestling. Along with Claybourne, at least three other famous black wrestlers of the era would use the nickname at one time or another, including Alex Kaffner (who also wrestled as Alexis Kaffir) and Jim Mitchell.

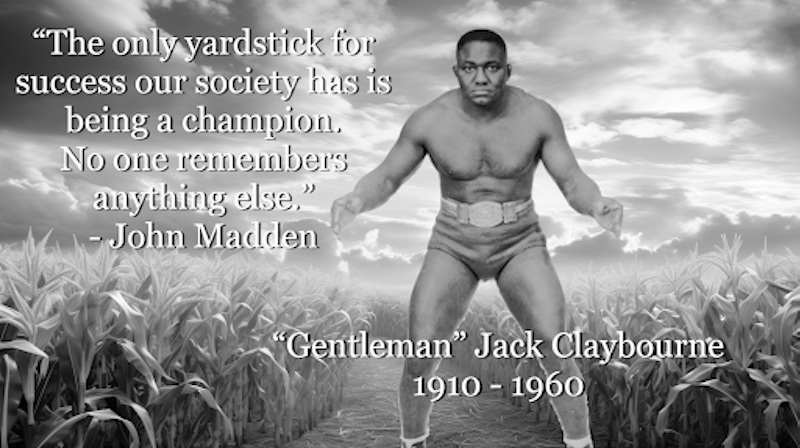

When Claybourne eventually reached Michigan and experienced true stardom, he was depicted as “Gentleman” Jack Claybourne, a heroic counterpoint to the top Black villain at the box office, “Rough” Rufus Jones. In developing his unique brand of carnage, Jones had mastered an offense that relied heavily on the creative delivery of furious headbutts throughout his matches, while Claybourne countered with a barrage of leg locks and dropkicks. During his feud with Jones, Claybourne pinned the established Black villain to earn acknowledgement from The Expositor of Brantford, Ontario as the unofficial Negro light-heavyweight champion of the world. Once again, Claybourne was a world champion, but none of these titles were seen as legitimate. This was a practice that reflected the way “colored championships” were treated in the world of boxing. A pugilist’s claims to be the colored or Negro world champion were generally the result of self-proclamations that carried enough truth to them that they were honored by other promoters and fighters.

Moreover, by the late-1930s, boxing had generally discontinued the practice of giving even tacit acknowledgement to such race-based claims on world championships. Across the major weight classes, fighters like Joe Louis, Tiger Flowers, Gorilla Jones, Jack Thompson, and Ray Robinson had cobbled together enough world title reigns in the prior two decades to dispel any notion that such separations were essential.

Even in the fictitious world of pro wrestling, none of Claybourne’s Negro world titles were bestowed with even a shadow of authentic recognition until he ventured south to Kentucky. It was there that Claybourne dueled with Jim Mitchell and Seelie Samara, capturing the Kentucky version of the Negro world heavyweight championship in 1941.

After spending a year in Ohio, Claybourne moved to New York in 1943, where he’d adopt the name of “Tiger” Jack Claybourne, which was a tribute to Black wrestling star “Tiger” Jack Nelson, who had himself borrowed the name from “Tiger” Ted Flowers, boxing’s first Black middleweight champion. From there, Claybourne would move to Maine and California, and he was declared as the Negro world heavyweight titleholder in both places. In Los Angeles, the title was as legitimate as such race-based championships could be, as “Tiger” Jack Nelson had long ago established a world championship belt to be contested for exclusively amongst Black wrestlers in California. Claybourne won the title from Seelie Samara, defeating him in February of 1945 in straight falls to win the championship and the title belt.

Future events would suggest that Claybourne grew accustomed to the weight of championship gold around his waist. After spending the better part of 1946 and 1947 touring Australia and New Zealand while labeled as the Negro world heavyweight champion, Claybourne seized 1948 as the year to take the concept of a Negro world championship to a higher plane. When Claybourne arrived in Hawaii at the tail end of 1948, his waist was adorned by a diamond-studded Negro world title belt that he claimed was awarded to him by the New York State Athletic Commission.

As Claybourne dismissed the challenge of fellow Black wrestler Seelie Samara with the statement, “I don’t think I’d have much to worry about,” writer Dan McGuire of The Honolulu Advertiser described Claybourne’s world title trinket with more than a hint of awe. “It is studded with 21 diamonds and is indeed a thing of beauty,” McGuire wrote. “No wonder Samara would like to fasten it around his middle.”

Jack Claybourne and his wife Lillian arrive in Hawaii in December of 1948

(Courtesy of the The Honolulu Advertiser)

Claybourne even offered up a backstory for his new belt. According to the championship claimant, the belt in his possession was allegedly first won by California legend Tiger Nelson in 1941, then captured from Nelson by “Rough” Rufus Jones in 1943. Shortly thereafter, Claybourne dethroned Jones to claim the championship, and reigned steadily for five years.

What’s most impressive about Claybourne’s story is that it sounds slightly plausible at first blush. As previously mentioned, Tiger Nelson introduced his own gold-and-diamond championship belt while wrestling in Los Angeles, claiming to have won it “years ago” in a tournament in New York City. Nelson then went on to defend his belt exclusively on the West Coast, claiming the title of “World’s Colored Heavyweight Champion.”

Upon studying dates and geographies, Claybourne’s tale falls apart. Tiger Nelson introduced Californians to his title belt in the mid-1930s, and the careers and wrestling locations of Nelson and Jones didn’t intersect in any way that would’ve allowed for an in-ring exchange of Nelson’s self-proclaimed world title. While Jones and Claybourne shared the ring dozens of times in the late-1930s, they never wrestled one another again after 1942.

The timing of Claybourne’s declaration that he was a Negro world champion recognized by a power that superseded territorial boundaries is unlikely to have been a mere coincidence. Just three months prior, the National Wrestling Alliance was officially founded, creating a world title with authority that crossed borders. It also forged an organization that punished any promoter claiming to advertise an alternate world title, or any wrestler claiming to possess one.

Jack Claybourne as the “NYSAC Negro World Heavyweight Champion” in 1948

(Courtesy of The Honolulu Advertiser)

Perhaps believing his title could fly beneath the NWA’s radar, Claybourne tied the authenticity of his title to arguably the most legitimate sanctioning body in combat sports at the time. The foremost issue with this was that it was untrue; the NYSAC hadn’t even recognized Negro world championships in any professional boxing weight classes, let alone in professional wrestling. Moreover, while the NYSAC did sanction a world heavyweight title for wrestling—the NYSAC World Heavyweight Championship—it discontinued the official recognition of any such champions following the retirement of the title’s final holder Jim Londos in 1946.

Regardless, as the National Wrestling Alliance took several years to fully consolidate its power, Claybourne made the most of being the wrestling world’s lone traveling Negro World Heavyweight Champion with a fancy belt to prove it. As a popular performer in Hawaii, Claybourne quickly added a race-neutral championship belt—that of the “Ring Magazine” Hawaii Heavyweight Wrestling Champion—to his haul. Claybourne subsequently traveled back to Australia and New Zealand with his Negro title belt in tow, engaging in international defenses of his championship against other traveling Black wrestlers.

The overwhelming majority of Claybourne’s title defenses were made against his mentee and travel companion, the young Buddy Jackson. It was during a promotional interview intended to drive the hype for one of his title defenses against Jackson, in April of 1952, that Claybourne was asked for a list of the best Black wrestlers in the world by a reporter from The Alabama Tribune.

Jack Claybourne vs. Buddy Jackson in 1952

(Courtesy of The Alabama Tribune)

After first offering a show of deference to the recently departed Black legends Reginald Siki and Rufus Jones, Claybourne listed Don Blackmon, Seelie Samara, Frank James, Don Kindred, Woody Strode, and Jim Mitchell as the best Black wrestlers in the business. Presumably, Claybourne would also have added the names of himself and Jackson to that tally, even though such a label would’ve been premature in Jackson’s case.

Claybourne’s hastily-crafted list became the closest thing in existence to a top Black wrestler of the early-1950s, cobbling together an unofficial top-10 ranking of Black professional wrestlers. It was a case of one of the most respected and well-traveled Black wrestlers of his era assembling a list of the performers of his era that most mattered to him.

The timing of the list is critical, and a testament to how rapidly a changing of the guard can take place on the pro wrestling scene. One decade earlier, Claybourne’s list likely would’ve included Gorilla Parker, “Cyclone” Johnny Cobb, Tiger Nelson, Leroy “King Kong” Clayton, and Alex Kaffner. One decade later, all of these performers’ names were washed away by the fame of Bobo Brazil, “Sailor” Art Thomas, Bearcat Wright, Luther Lindsay, and a handful of other wrestlers whose legacies were easier to observe and recall thanks to the proliferation of television programming and the preservation of territorial wrestling histories.

It was during the period between 1948 and 1952 that Claybourne’s in-ring style underwent a dramatic change. While the earliest descriptions of Claybourne’s style hailed him as an acrobat and a “dropkick expert” who’d routinely pin his opponents following a flurry of sequential dropkicks, his tactics began to resemble those of Rufus Jones. Claybourne’s dropkick total gradually declined and gave way to an increasing number of headbutts, until Claybourne came to be regarded almost exclusively as a headbutter.

The headbutt-heavy style popularized by Jones required substantially less effort to pull off. It could also enable an age- or injury-addled wrestler to stay upright for longer stretches of bouts and absorb fewer bumps on the wrestling mat.

Claybourne’s style alteration may also have been in response to his weight gain. While the earliest descriptions of “Jumping Jack” listed him as 180 pounds, the official weight of “Gentleman Jack” was listed in travel documents as 205 pounds in the 1940s, and closer to 240 pounds by the 1950s. While professional wrestlers inflate their weights for the sake of exaggerating the mass of the match participants, accumulating 50 pounds of body weight over a 20-year period has a tendency to slow and ground wrestlers who once preferred to fly.

While Claybourne enjoyed a nearly six-year run with the status of a traveling world champion of sorts, several factors eventually coalesced to remove Claybourne from his perch. It began when Claybourne’s efforts to promote himself as a world champion sanctioned by the New York State Athletic Commission apparently caught up with him. The story offered for public consumption was that Claybourne was pulled from a match in Buffalo in September of 1954 due to his failure to pass a physical examination. However, The Buffalo News published the story on September 14th that the New York State Athletic Commission had permanently suspended Claybourne from ever competing in New York rings again.

It’s uncertain whether this ban was legitimately carried out by the New York State Athletic Commission, or if it was the first stage of a blackballing effort by the National Wrestling Alliance against Claybourne in response to his self-promotion as a world champion. However, the circumstantial evidence is that the latter is true, because Claybourne never wrestled on U.S. soil east of the Mississippi River ever again, nor did he ever make any further claims to being a Black world heavyweight champion.

The second factor working against Claybourne was the emergence of the next generation of young, Black wrestling thoroughbreds. When paired with a 5’8” wrestler like Luther Lindsay, an elder statesman like Claybourne could get by on his reputation as the veteran of the team. The tandem would capture the NWA Open Tag Team Championship in Toronto in the fall of 1954.

The serious threats to Claybourne’s supremacy arrived in the forms of Bearcat Wright and Bobo Brazil, both of whom were younger, stronger, and plainly larger than Claybourne. In fact, Claybourne had teamed with the 6’7” Wright in Buffalo, New York late that same summer, right before Claybourne was banned from New York and forced to move to Toronto to team with Lindsay.

By December, Wright was announced as Claybourne’s full-time replacement on the team with Lindsay, with The Toronto Star reporting that the substitution had been no reflection on Claybourne’s ring ability, or more specifically, its declining quality. The audience was meant to believe it was purely a coincidence that Claybourne surrendered his spot to a larger, more vibrant wrestler who was also two decades younger.

Similarly, when Claybourne shared the ring with Bobo Brazil, there was apparently nothing he could do to outclass a muscular 6’6” wrestler who was 13 years his junior. It didn’t help that The Honolulu Advertiser described Brazil as “greater than Jack Claybourne” before he even debuted.

By this point, both grapplers were now playing the Black-wrestler headbutt game that was first established by headbutt king Rufus Jones in the 1930s. With Claybourne and Brazil partnered together in Hawaii, Brazil delivered performances that were both more convincing and compelling. By the time May rolled around, former Hawaiian champ Claybourne found himself in the curtain-jerker position during a card at Honolulu’s Civic Auditorium while Brazil main-evented that show against NWA World Heavyweight Champion Lou Thesz.

For what it’s worth, Brazil’s coronation as wrestling’s premier Black performer coincided with the final tour of Hawaii that Claybourne was ever offered. Claybourne then spent 1958—his final year of noteworthy ring activity—on the losing end of matches in New Mexico.

Claybourne’s name would enjoy a peculiar resurgence well into the aftermath of his suicide. Martinican wrestler Edouard Etifier—who wrestled as Eddie Morrow in North America—would adopt the name Jack Claybourne Jr. for his tours of New Zealand, Australia, and most notably for the International Wrestling Association of Japan. This utilization of the deceased Claybourne’s name would transpire a full 10 years after his death.

In that respect, Claybourne joined Rufus Jones as a Black legend from a bygone era whose entire name was lifted by a wrestler of the generation that succeeded him. It’s also somewhat fitting, considering how many Black wrestling legends Claybourne had directly borrowed from—in both his names and wrestling styles—from the generation preceding his.

It was a testament to the original Jack Claybourne’s legacy that he was one of the Black wrestling icons deemed worthy of a name-identical successor, inasmuch as every Black wrestling champion who ever aspired to carry a world-title distinction across borders exists squarely within Claybourne’s legacy. That’s one accolade that neither time nor any premeditated act of self-slaughter could ever strip him of.