Anyone who’s wondering whether or not the ghosts of professional wrestling’s racist past are still hovering over the industry need look no further than the Black induction rates of the most visible institutions claiming to be genuine professional wrestling halls of fame.

Almost every year since its inception, the World Wrestling Entertainment Hall of Fame has inducted at least one wrestler, manager, or affiliated celebrity of at least partial African descent. The obligatory nature of these inductions hasn’t escaped notice, and the announcements of several of the honorees have been met with eyerolls.

Presumably, these acts of predictable corporate acquiescence transpire because of the public-facing nature of WWE, and its desire to avoid whatever backlash might result from the perception of anti-Black racism in the procedure for selecting its nominees. Whatever the rationale, the outcome has been conspicuous.

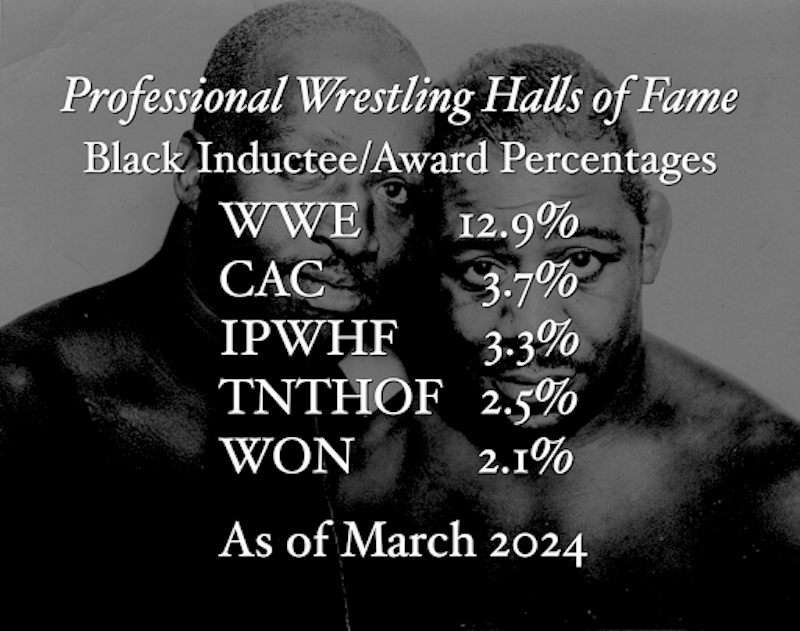

As of 2023, just under 13 percent of the WWE’s Hall of Fame honorees have been Black, although wrestling fans are required to play along with the perceived silliness of some of the decision-making to arrive at this figure. For instance, Booker T received two separate inductions over a seven-year—period—once as an individual, and again alongside his brother and Harlem Heat tag-team partner Stevie Ray. There have also been celebrity honorees, like Snoop Dogg, William “Refrigerator” Perry, Mr. T, and Mike Tyson. Then there are the award recipients who’ve technically qualified as members of the induction classes, like Titus O’Neil and Shad Gaspard, and also wrestlers hustled in through the back door via sweeping Legacy-wing inductions, like Brickhouse Brown and Pez Whatley.

Among the common responses to selections like these—aside from the eyerolls, accusations of pandering, and I-see-what-they’re-doing statements—is the inevitable reminder that the WWE Hall of Fame isn’t real. There is no physical WWE Hall of Fame. It’s a figment of the imagination. It doesn’t exist outside of the imaginations of fans, and its virtual home on the WWE website.

"It's hard to compare the WWE Hall of Fame with more traditional entities in other sports," wrestling historian Jonathan Snowden, author of Shooters: The Toughest Men in Professional Wrestling said. "The WWE doesn't have voters, or even a criteria for entry. It has long been based on the whims of a single man, Vince McMahon. The typical WWE Hall of Fame class includes one major star of the modern era as the headliner, one woman, one celebrity and others selected without rhyme or reason. It's a collection of top stars and also less central figures like Queen Sharmell and Ivan Putski. To be honest, it's a kind of meaningless award on the merits. But, because it's a televised event with the WWE imprimatur, it's likely the wrestling hall of fame that means the most to talent."

The ways in which WWE artificially boosts its roster of Black hall-of-fame members draws attention to a related issue: When you examine the lists of Black inductees at other professional wrestling halls of fame—including those housed within physical structures—the story is bleak. At most of professional wrestling’s most respected halls of fame, the percentage of Black inductees is lucky to crack three percent.

Over at the International Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Albany, New York, there have been 52 wrestlers inducted to date, with a further eight awards handed out. Of those 60 honors conferred upon professional wrestlers and other contributors of significance, two have been granted to Black recipients. It could’ve been worse; had the IPWHF not inducted Bobo Brazil and Reginald Siki in 2023, that number would be zero.

In fairness to the IPWHF, it’s a very young institution with hopefully many more years of inductions ahead of them, and plenty of opportunities to boost those numbers. To their credit, the IPWHF also presents an annual award named in honor of Black wrestling legend Rocky Johnson. In general, the IPWHF selection committee also does a far better job than several other wrestling halls of fame at honoring pre-1950s wrestlers.

Wrestling historian and author John Cosper hopes this will soon result in Black wrestling legends like “Gentleman” Jack Claybourne, “Black Panther” Jim Mitchell, Woody Strode, and the original Rufus Jones receiving inductions.

“For decades, the narrative about African American wrestlers began with one man: Bobo Brazil. A beloved star who broke the color barrier in many cities—including Jim Mitchell’s hometown of Louisville—Brazil is rightly remembered by fans and historians as a legend,” explained Cosper, who wrote a biography about the aforementioned Mitchell. “But Brazil owes his place in history in part to the generation that came before. To Jack Claybourne, Rufus Jones, Seelie Samara, Jim Mitchell, and others. These men, in turn, were inspired to pursue their pro wrestling dream by men who came before them, going back to Viro Small in the late 1800s.”

As it stands, 3.3 percent of the IPWHF’s honorees have been Black, which is still a higher rate than some of its competing halls of fame. If you travel over to Waterloo, Iowa—the home of the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame (usually shortened to TNTHOF) inside of the National Wrestling Hall of Fame and Museum—the Black honoree percentage is 2.5 percent.

The TNTHOF has inducted 87 wrestlers and handed out a further 70 awards for a total of 157 honors. Of those 157 recipients, only four have been Black. That includes the lone Black TNTHOF inductee Luther Lindsay, and it also counts Daniel Cormier, who received an award for his success in mixed martial arts.

"They are called wrestling halls of fame, but fame is not always the main consideration," Snowden added. "Style and quality of work is also paramount. For the more traditional halls, the perceived ability to shoot and wrestle 'for real' matters a lot. When wrestlers are rated by their older peers, in particular, that seems to be of significant concern.”

Delving further into the percentage of Black honorees at the Cauliflower Alley Club—which has established a hall of fame of sorts—is trickier. This is because the CAC initially went out of its way to honor boxers and actors alongside wrestlers, and the names of many of the early honorees of the Cauliflower Alley Club reflected this.

To simplify the math, begin in 2000 and only consider clearly identifiable wrestlers who’ve received awards or another form of commendation from the CAC, not including scholarships. After making these adjustments, 11 of the CAC’s roughly 300 award recipients since 2000 have been Black. Of that number, nine honors have been administered since 2010, with five distributed since 2020.

This represents a drastic escalation in the Black recipient rate of CAC awards since Brian Blair took over as president of the CAC; since 2020, a full 13 percent of CAC awards have been bestowed upon Black honorees, which matches the WWE Hall of Fame’s total rate of conferring honors upon Black recipients. According to Blair, this escalation was no accident.

“Since I became the president and CEO of the CAC 10 years ago, I wanted to keep the traditions that I was taught, while always making sure that the honorees were well-deserving, without any type of prejudice,” explained Blair. “I personally felt like there were not enough Black athletes being represented in the CAC, especially knowing so many of my peers that were masters at their craft and happened to be Black. Ron Simmons, Koko B. Ware and Jacqueline Moore—just to name a few—have been tremendous and well-deserving additions to our CAC Hall of Fame.”

Of all the wrestling halls of fame, the selection process for The Wrestling Observer Newsletter most closely mirrors that of a major spectator sport’s hall of fame. A panel of writers, historians, former wrestlers, and otherwise knowledgeable wrestling minds selects honorees from a list of candidates, and with would-be hall-of-fame members required to surpass a 60-percent vote threshold in order to be successfully granted induction.

Since the WON Hall of Fame first took shape in 1996, there have been more than 280 individuals elected, although this also includes some honorees inducted twice. Of honorees, only six have been Black: Abdullah the Butcher, Bobo Brazil, Ernie Ladd, Bearcat Wright, Carlos Colon, and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. It’s worth noting that Johnson has equal claim to Samoan heritage, and that Colon’s from Puerto Rico, where racial admixture is very high. Even counting all six of these inductees as equally Black, that sets the WON percentage of Black inductees as just above two percent.

At a glance, the induction percentages of the WON Hall of Fame are heavily skewed by the number of inductees who spent their careers wrestling almost exclusively in Mexico and Japan. Still, excluding those 80-plus wrestlers from the math only manages to boost the Black percentage of the WON Hall of Fame’s makeup to three percent.

We can try to find some explanations for why the representation levels of Black wrestlers in these halls of fame are so low. The WON is a great place to start, as part of the logic behind the numbers might be evident in what’s skewing them so dramatically.

Specifically, the perceived overrepresentation of Asian and Latino wrestlers in the WON Hall of Fame reflects the thriving professional wrestling industries that have existed in Mexico and Japan for decades, as well as the readership that The Wrestling Observer has attracted to those companies. As both countries develop and elevate talent primarily from within their surrounding populations, the decades of wrestling history in both nations is replete with titlists and attractions whose accomplishments can be easily traced and appreciated.

Comparing that to the broader Black experience in professional wrestling, it’s easy to see the differences in the historical experiences of the different sets of wrestlers. For the majority of professional wrestling’s existence, Black American wrestlers found themselves vying for a scant few positions in a limited number of territories within which there were unwritten rules about how many Black wrestlers you could employ at one time, how high those wrestlers were permitted to climb on the card, and how they were required to wrestle in order to sustain employment. In addition, attempts to run all-Black wrestling organizations—of which there were a few in the 1940s—were snuffed out by the National Wrestling Alliance monopoly.

What is the consequence of this? When credentials like drawing ability, number of titles held, and the prestige of titles are factored into the equation, very few Black wrestlers were placed in positions where they could present respectable hall-of-fame cases to voters in comparison with many of their non-Black peers. Therefore, wrestling historians looking at Black wrestlers’ title histories and main-event runs as evidence of competence often find the cupboards relatively bare.

As an example of the importance of this and how it can work in a wrestler’s favor, Carlos Colon—one of the six Black WON HOF inductees—was also the co-owner of Puerto Rico’s World Wrestling Council. This enabled Colon to rack up an astronomical championship tally that didn’t work against him when it was time to weigh his accomplishments. Had Colon been forced to wrestle on the U.S. mainland for the entirety of his career, it’s impossible to imagine that American wrestling bookers would’ve treated him so favorably.

Then there’s the question of “workrate,” a word that often encapsulates a wrestler’s believability, athleticism, and endurance in varying proportions depending upon whom you ask to define it. Historically, Black wrestlers have fared poorly relative to the workrate test, and those who have fared admirably at times—like 2 Cold Scorpio, Shelton Benjamin, or Dorrell Dixon—usually fall short by some other measurement standard used to gauge hall-of-fame worthiness.

“In a hall of fame with more modern concerns, like that of Dave Meltzer's Wrestling Observer, workrate replaces realism as a key issue,” Snowden said. “Wrestlers who have matches that wow fans and media with innovative moves are favored over wrestlers whose stardom is built more on personality and the ability to connect with fans through promos and interviews. For Meltzer's hall of fame, in particular, successfully wrestling in Japan is a key part of most contemporary cases. It's why you see lesser stars by any objective standard, like Steve Williams, inducted ahead of top performers like Sting or Lex Luger."

Using the match ratings supplied by The Wrestling Observer Newsletter as a proxy for a wrestler’s ability to wrestle an elite match, and using The Wrestling Observer’s usual ceiling of five-stars to identify a match that’s essentially perfect, only five Black wrestlers have ever cracked the five-star barrier out of the roughly 250 matches that have earned five stars or more. Those wrestlers are Ricky Starks, Keith Lee, Ricochet, Velveteen Dream, and Butch Reed.

Moreover, 34 years elapsed between the bouts by Butch Reed and Ricochet that earned five-star ratings in The Wrestling Observer, reflecting more than three decades of inability on behalf of Black wrestlers to sway editorial opinions in favor of bestowing such an honor upon them.

This isn’t to suggest that there’s anything even remotely racist about Dave Meltzer’s star-rating system, or the match-rating systems of anyone else. What it does insinuate is that the side door through which some wrestlers have gained entry to the WON Hall of Fame—by participating in a series of matches that have been generally regarded as masterpieces on the face of their technical and artistic merits—hasn’t been open to Black wrestlers. This is potentially owed to periods in wrestling history where Black performers wrestled in styles that weren't conducive to displays of technical brilliance.

"Wrestling, by ‘controlling’ competition, really prevented anything resembling a level ‘working’ field,” expressed Oliver Bateman, wrestling historian, and writer for The Ringer. “If the promoter actually tells you that you cannot use your athleticism to wow fans with workrate masterpieces—that you, despite being an Olympic bronze medalist in judo, have to work a punch-and-kick ‘ghetto blaster’ style like Allen Coage did in WWE—then you are essentially stuck below an unbreakable cement ceiling. You can’t become an all-time great because they won’t let you. It’s not in the script.”

In the meantime, what this has meant to the WON Hall of Fame is there hasn’t yet been a single Black wrestler inducted who debuted prior to 1950, or after 1970, with the lone exception of The Rock.

It’s not like the missing decades of Black enshrinees are an accident given the collapse of the wrestling territories and the rise of WWE—which was previously known as the World Wrestling Federation—and competing national wrestling organizations. Within the NWA’s territorial system, where events were often held in the same seven or eight cities every single week for months on end, bookers had a financial incentive to appeal to ethnic enclaves within their individual territories if fans in those communities were willing to show up in large numbers and purchase tickets.

This was a more favorable system than that which preceded it during the 1930s and 1940s, when Black wrestlers like Jack Claybourne often had to invent their own world Negro titles in order have any claim on championship status. The NWA’s territorial system resulted in Black wrestlers like Ernie Ladd, Thunderbolt Patterson, and Rocky Johnson regularly stockpiling championship reigns across several wrestling territories.

By percentage, championship reigns by Black wrestlers fell off a steep cliff during the 1980s, likely as a byproduct of U.S. wrestling’s nationalization and the desire to appeal to an American television audience that was 80 percent white, and 11 percent Black. If we generously declare that 1983 was the year that true nationalization attempts took place within the wrestling industry, here’s every single Black championship reign of any kind from the 1980s that occurred within the World Wrestling Federation, the National Wrestling Alliance as overseen by Jim Crockett Promotions, and the American Wrestling Association:

Rocky Johnson and Tony Atlas: WWF World Tag Team Champions (1983).

That’s the entire list. Now, lest any naysayers suggest this data has been cherry-picked to artificially shorten this list, the only title reigns omitted by not starting the timetable in 1980 are the NWA Television Championship reigns of Rocky Johnson and Leroy Brown, which occurred before that championship received a status upgrade beyond the Mid-Atlantic. If we start the clock when it’s almost universally agreed upon that the WWF’s national expansion ambitions began—when Hulk Hogan captured the WWF title in 1984—there wouldn’t be any list at all.

Given the paucity of title reigns by Black wrestlers, should it come as any surprise that Black wrestling fans so fondly remember the reign of Mike “Virgil” Jones with the unsanctioned Million Dollar Championship in 1991? That was the first time a Black wrestler was seen holding any sort of individual gold in a national wrestling promotion.

No Black wrestler would touch a sanctioned WWF title again until Men On A Mission enjoyed a two-day reign with the tag belts in England in 1994. Further, no Black wrestler would appear on television holding a sanctioned WWF singles championship of any kind until Ahmed Johnson won the WWF Intercontinental Heavyweight Championship in 1996.

By comparison, Black wrestlers went completely untitled in the national iterations of both the AWA and NWA during the 1980s. Butch Reed and Ron Simmons finally broke through and won the NWA World Tag Team Championship in 1990. Simmons became the first Black holder of the WCW World Heavyweight Championship in 1992. From there, Booker T became the first Black wrestler to hold either the WCW World Television Championship or the WCW United States Heavyweight Championship, capturing them in 1997 and 2001 respectively.

The outcomes of Black wrestlers in these simulated wrestling competitions stands in stark contrast to the results achieved by elite Black athletes in authentic combat sports. The world titles of the majority of professional boxing’s original eight weight divisions had been in the possession of at least one Black fighter by 1930. In reflecting the reality of the combat sports world, pro wrestling was trailing legitimate sports by half a century.

To summarize these findings, if major championships are a prerequisite to hall of fame candidacy, Black wrestlers generally weren’t granted opportunities to even touch championship belts of any worth in the eyes of hall-of-fame selectors for the better part of a decade, and even then, title reigns were few, and limited to the tiniest handful of performers. This is a key reason why Black WWE standouts from the 1980s like Mike “Virgil” Jones and “Bad News” Brown (Allen Coage)—both of whom held territorial titles prior to being hired by WWE —are dismissed as wrestlers with inferior hall-of-fame credentials. It’s also why a wrestler with slightly more territorial gold than the aforementioned pair, like Koko B. Ware, was perceived as unworthy when he was selected for induction into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2009.

“It’s the sins of the past that created a shallow pool of potential honorees,” stated Cosper. “The McMahons and the WWE were right to mandate honoring Black wrestlers, but Vince and his father were just as guilty of not giving more Black wrestlers a friendly platform.”

If we examine the number of main-event pay-per-view appearances by Black wrestlers during the same decade, the list looks like this:

WrestleMania I: Mr. T (Tag Match),

The Wrestling Classic: The Junkyard Dog (Tournament Final).

Survivor Series 1987: Butch Reed (Elimination Match).

Survivor Series 1988: Koko B. Ware (Elimination Match).

SummerSlam 1989: Tiny “Zeus” Lister (Tag Match).

No Holds Barred: The Match/The Movie: Tiny “Zeus” Lister (Tag Match).

This list is generous in as much as The Junkyard Dog’s main-event appearance at The Wrestling Classic was in an unanticipated tournament final against Randy Savage, and the advertised main event of the night involved Hulk Hogan defending his world title against Roddy Piper.

The Survivor Series main-event appearances by Reed and Ware enabled them to serve as pin-fodder on five-man teams captained by star attractions like Hulk Hogan, Savage, and Andre the Giant. The only true main-event appearances by Black wrestlers on pay-per-views during the 1980s were by Hollywood actors in part-time supporting roles. This list would also remain exhaustive even if you included all nine of the non-pay-per-view Clash of the Champions events presented by Jim Crockett Promotions and WCW during the 1980s.

During the entirety of the WWE’s early “Hulkamania” era, stretching from 1985’s WrestleMania to the 1993 King of the Ring, fans were treated to just over 50 match appearances by full-time Black wrestlers over the course of nearly 30 pay-per-view events. More than 40 of those appearances were logged by five men: The Junkyard Dog, Koko B. Ware, Butch Reed, Bad News Brown, and Virgil. It’s figures like this that underscore why the WWE scrambled to find Black wrestlers who have enough ring time in the spotlight to qualify for hall-of-fame candidacy.

Then there’s the different matter of how Black wrestlers have been depicted in WWE rings when the lights have shined the brightest. When you consider all of the match finishes that took place over the course of the first 20 WrestleManias—a period of time stretching from 1985 to 2004—here is every match finish in which a Black wrestler achieved a victory for either themself or team by personally applying the pinfall or submission to an opponent:

WrestleMania III: Butch Reed pinned Koko B. Ware.

WrestleMania VII: Koko B. Ware defeated the Brooklyn Brawler (Dark Match).

WrestleMania XI: Lawrence Taylor pinned Bam Bam Bigelow.

WrestleMania XIII: Rocky Maivia pinned the Sultan.

WrestleMania XV: Jacqueline pinned Ivory (Sunday Night Heat Match).

WrestleMania X8: The Rock pinned Hulk Hogan.

WrestleMania X8: Jazz pinned Lita.

WrestleMania XIX: Shelton Benjamin pinned Chavo Guerrero.

WrestleMania XIX: The Rock pinned Steve Austin.

To put the first four of these nine Black wrestling wins in 20 WrestleManias into perspective, the first victory on the list involved one Black wrestler defeating another Black wrestler. The second occurred in a dark match that never aired. The third was by a professional football player in his match—which is also his only match to date—and also the first time a Black “wrestler” main-evented WrestleMania in a singles match. The fourth involved a multi-racial wrestler of half-Black, half-Samoan, multi-generational wrestling royalty awarded a pinfall victory over a Samoan wrestler pretending to be of Arab descent.

Then there’s racial definitions. Let’s define an incontestably Black wrestler as a wrestler with two Black parents, which is fair given the premise that we’d typically define a white wrestler as possessing two white parents. If we apply this standard, the first time a Black wrestler pinned or submitted a non-Black wrestler during an official WrestleMania event to conclude a match happened when Jazz secured a victory against Trish Stratus and Lita in the WWF Women’s Championship match at WrestleMania X8. Jacqueline’s victory over Ivory to open WrestleMania XV was technically part of the Sunday Night Heat broadcast that was viewable on free television and preceded the WrestleMania XV pay-per-view.

If you’re wondering when the first time that a full-blown Black man meeting all of the same definitional requirements secured a pinfall win at a WrestleMania event, it was Shelton Benjamin winning a tag match for Team Angle at WrestleMania XIX. Are you searching for the first time a fully Black wrestler pinned or submitted a non-Black wrestler straight-up in a one-on-one match at WrestleMania? That took place at WrestleMania 29 when Mark Henry pinned Ryback.

It took more than a decade of WrestleManias for a full-time, half-Black wrestler on the WWE roster to achieve a visible pinfall victory over a non-Black opponent as part of the main broadcast. It took nearly two decades for a fully Black wrestler to do the same, in any format. It took almost 30 years for a similarly defined Black male wrestler to pin a White male wrestler in a one-on-one contest at WrestleMania. All of these observations are representative of an era in which Black wrestlers often went un-pushed, untitled, and underutilized.

“Pro wrestling had the worst record on race over a 30 year period when Black athletes were prominent in every other major sport except hockey,” added Bateman. “And even there, Grant Fuhr of the Edmonton Oilers outperformed every Black athlete in wrestling up to the arrival of The Rock at least.”

What’s the remedy? The WON might consider following the example set by the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. That’s where the Veterans Committee reviews the credentials of prior candidates for induction whose names have fallen off the ballot of the National Baseball Writers’ Association. It’s a measure put in place to ensure that Cooperstown eventually gets it right, and that no one truly deserving of enshrinement is left out in the cold. Professional wrestling’s halls of fame could benefit from a similar safety net.

As for the other pro wrestling halls of fame, where the selection process is probably less dependent upon such stringent voting procedures, it may simply be a matter of having someone in the room whose job it is to survey the scene, and then speak up and say, “Are we sure we’re not forgetting someone?”

To a historian like Cosper, recent research that has shed further light on the accomplishments of men like Jim Mitchell, Jack Claybourne, Rufus Jones, Alex Kaffner, Seelie Samara, Johnny Cobb, and dozens of other Black wrestlers has left the modern institutions that have self-selected themselves as caretakers of pro wrestling’s history with no choice but to honor them.

“These men were legitimate stars in arenas across the country and around the world,” insists Cosper. “Once lost to history, they now cry out to us from the past. We had an excuse previously for not thinking of them. Their stories were buried; not maliciously, but buried nonetheless. It’s up to us to make sure future generations do know their names. There are no excuses. Just record after record telling us that men like Mitchell, Jones, and Claybourne earned their places of honor.”

None of this information necessarily suggests that the percentages of Black pro wrestling inductees would jump exponentially even if another dozen Black wrestlers suddenly received hall of fame inductions. What it does betray is the presence of a collection of invisible historical hiccups that factor into the modern candidate-selection process. They’re the unintended consequences of multiple eras in professional wrestling history that have now left decades’ worth of Black wrestlers without the required credentials to dazzle most modern hall-of-fame selectors, and earn their passage to the realm of wrestling immortality.