Lambert & Stamp, a fascinating new documentary, has just been released on video. It tells the story of Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, two British men who in the early 1960s set out to make a film and wound up managing The Who. The film’s worth seeing not only for Who fans, but as a window into how much our modern culture has been homogenized by the steamroller of “diversity.” Lambert & Stamp is a bubbly and poignant window into a time when true diversity—that is, the diversity of human beings acting more as individuals and less as groups—could create a rich social life as well as explosive artistic magic.

It’s an especially important message right now. A recent Vanity Fair photo of late-night TV hosts has been met with (of course) outrage because all of the people in the picture are men (and most of them white).

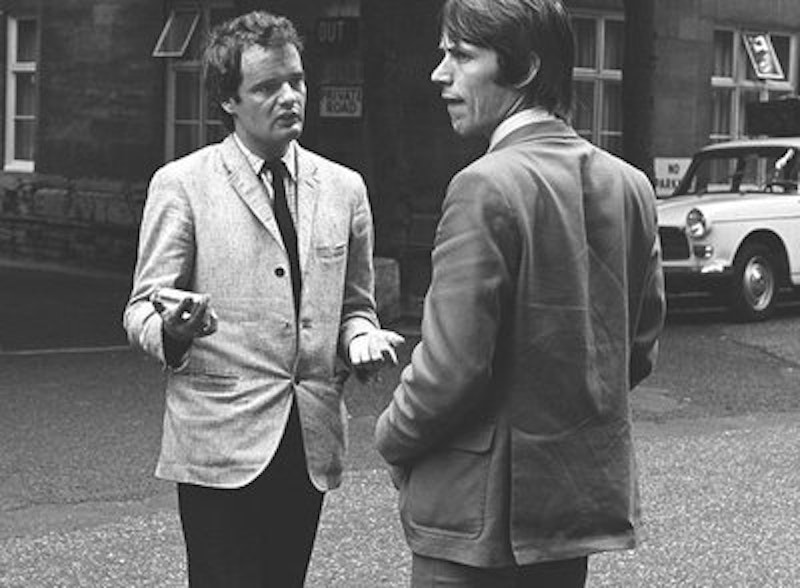

Our culture has gotten to a sad and dangerous place when the first reaction to a photo is to reduce the people in the picture to their race and/or sex. It makes one long for times when people were treated as individuals (and yes racists treated people as groups, and that was wrong). In the early-60s in London Kit Lambert, the gay and “posh” son of a classical composer, and Chris Stamp, the working-class son of a tugboat captain, met in a pub. Both men wanted to make a film, and decided to join up and do it together. At the time London was kinetic with subcultures—mods, rockers, musicians, art school kids, filmmakers, and fashionistas—and Lambert and Stamp came up with a plan: they would find an exciting rock ‘n’ roll band and make them the subject of their film.

They found The Who, “a group of misfits,” as Stamp puts it. Guitarist Pete Townshend, singer Roger Daltrey, bassist John Entwhistle and drummer Keith Moon were not pin-up idols; in fact they were barely housebroken. It would be hard to imagine four more different people getting together—Townshend, the art school mystic; Daltrey, the tough street hood; Entwhistle, the well-dressed stoic; and Moon, the charismatic and hilarious lunatic. But when the four played together, something raw, real, and thrilling happened.

What is so impressed upon the viewer of Lambert & Stamp, or at least it was on me, was how richly the people in the film are individuals. The film explores Lambert’s homosexuality and how it may have affected him in a time and place when being gay was illegal, but it doesn’t fetishize Lambert’s gayness. Furthermore, there were subcultures like the mods and rockers Townshend wrote about on the album Quadrophenia.

Still, there didn’t seem to be the relentless, obsessive impulse to relegate every single facet of your life to an expression of your race or politics (or gender). In 2015 we’ve gotten very good at identifying people by groups but we’ve lost the ability to see them as individuals. There are categories for geeks, frat guys, rockers, sorority girls, punks and entire races—“the black community”—but the result increasingly seems a flattening of distinctions rather than the flourishing of any kind of genuine diversity. I find someone’s transgenderism much less interesting than what books they read or if they believe in God.

One of my favorite pieces of writing about the profound and liberating importance of individuality is by Shelby Steele, a black scholar at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. Here is how the piece opens:

One day back in the late fifties, when I was ten or eleven years old, there was a moment when I experienced myself as an individual–as a separate consciousness–for the first time. I was walking home from the YMCA, which meant that I was passing out of the white Chicago suburb where the Y was located and crossing Halsted Street back into Phoenix, the tiny black suburb where I grew up. It was a languid summer afternoon, thick with the industrial-scented humidity of south Chicago that I can still smell and feel on my skin, though I sit today only blocks from the cool Pacific and more than forty years removed.

Into Phoenix no more than a block and I was struck by a thought that seemed beyond me. I have tried for years to remember it, but all my effort only pushes it further away. I do remember that it came to me with the completeness of an aphorism, as if the subconscious had already done the labor of crafting it into a fine phrase. What scared me a little at the time was its implication of a separate self with independent thoughts–a distinct self that might distill experience into all sorts of ideas for which I would then be responsible. That feeling of responsibility was my first real experience of myself as an individual–as someone who would have to navigate a separate and unpredictable consciousness through a world I already knew to be often unfair and always tense.

Steele’s realization tossed open the doors to a world of possibility. He could listen to and read whatever he wanted, go anywhere and make up his own mind about virtually anything. It’s hard to claim that such open ambition still exists in our politically-correct modern world.

One of the pivotal moments in Lambert & Stamp comes in the late-60s, when Lambert encouraged Pete Townshend to expand his sonic palette. Lambert’s father was Constance Lambert, a well-known classical composer and conductor, and Kit Lambert started giving Townshend copies of classical recordings. Townshend went from being a decent guitar player who wrote simple hits like “I Can’t Explain” to the composer of ambitious rock operas like Tommy and Quadrophenia. This artistic leap was possible through the best kind of diversity; Townshend, already surrounded by bandmates completely different from him—and already knowledgeable about rhythm and blues—went in a truly unexpected direction, classical and opera. It’s difficult to imagine Katy Perry or Kanye West, or any of the modern regulators of the level of testosterone in our blood or melatonin in our skin, being nearly as individualistic.

—Follow Mark Judge on Twitter: @markgjudge