The comics community was abuzz this week with the news that Atlantic writer Ta-Nehisi Coates has been signed on to write a new Black Panther series for Marvel comics, starting in spring. The excitement is well-warranted; Coates is one of the most respected writers on race in the U.S., and the Black Panther is generally credited as the first black superhero in mainstream comics publishing.

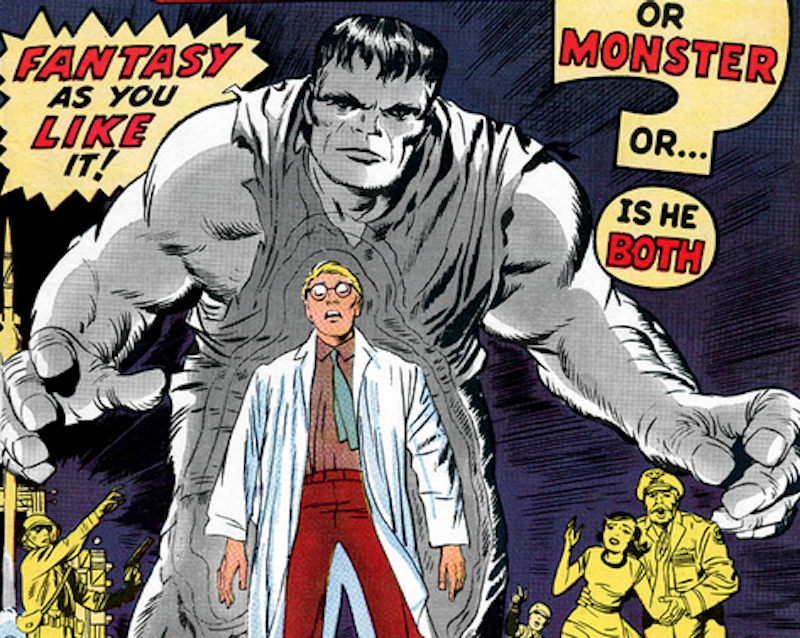

But while the Black Panther gets the attention and the glory, it’s rarely mentioned that years before he debuted in 1966, Jack Kirby and Stan Lee had invented another, even better known black hero: the Incredible Hulk. The Hulk isn’t usually thought of as a black hero. But in his first issue, in 1962, he was literally dark-skinned, with a slate-grey hide. Kirby and Lee only changed him to green later because the printers had trouble with the color.

Obviously, the Hulk is only literally black. He's not culturally African-American. Bruce Banner is a white guy before he transforms, and after he changes, the Hulk is a monster, not a black person. And yet in many ways the Hulk is a precursor of mainstream superhero blackness precisely because he’s actually white. A year after the Hulk was created, Kirby and Lee invented the X-Men, a superhero team of mutants. Mutants are presented as a stigmatized minority from the first issue—but in those first issues, all of those stigmatized mutants have white skin. The X-Men pick up on the long science-fiction tradition (dating back at least to War of the Worlds) in which violence and prejudice against people of color is appropriated for whites. Early on, Lee and Kirby established that in the Marvel universe, the most discriminated against characters are white people with super powers.

In this vein, the Hulk is even more blatant than the X-Men. He's a hunted monster, hated and despised for his abnormal dark skin. Yet he’s secretly a white man. The Hulk is a white person experiencing the prejudice directed at people of color; superhero narratives could sympathize with the victims of racial prejudice, but only when those victims were white.

Over the years Marvel comics and films have added more people of color to their ranks, from Storm to Idris Elba as Heimdall. But to some degree the erasure of blackness in plain sight has continued in superhero narratives. In the recent Fantastic Four film, Michael B Jordan was controversially cast as Johnny Storm, the Human Torch. Jordan’s a charismatic actor, and it was fun to see him in the role, but as scripted, the character could’ve been played by a white actor. The Thing and Dr. Doom are both stigmatized and alienated because of their appearance—and the Thing's monstrosity, in particular, has over the years been connected to his Jewishness. But that possible racial metaphor isn’t linked to Johnny, or to his father (played by Reginald E Cathey), nor is it examined in relation to his white adopted sister. As with the Hulk or the X-Men, the experience of blackness is given to white people. Meanwhile (again as with the Hulk) black heroes are presented as white heroes with a palette swap.

The Hulk foreshadows the treatment of other black heroes, then, in that his blackness isn't acknowledged as a cultural or social phenomenon. But he also foreshadows other black heroes in that he's a racist stereotype.

Bruce Banner gets angry and turns into a giant, black, physically overpowering monster–or, in other words, he turns into a stereotype of criminal, dangerous, black masculinity. After the Hulk lost his black skin, he became even more of a caricature, transforming not at night (as in the original version) but when he becomes angry. He also became dumber and dumber, losing access to first person pronouns (“Hulk smash!”) The recent Avengers film version of the character barely is so ape-like and animalistic he barely speaks. And then there was the run in the 1980s where Hulk turned gray again, got more intelligent—and became a gangland enforcer dressed in flamboyant attire, who displayed amazing sexual prowess.

Artists John Jennings and Stacey Robinson neatly skewer the Hulk’s racial subtext in their Black Kirby project with their character The Unkillable Buck. “Runs through bullets!” their two-fisted prose declares. The Hulk, they suggest, is derivative of the same racial panic which led Darren Wilson to see Mike Brown as a demon, and leads white people to attribute superhuman strength and endurance to black people. Banner’s alter ego functions as the first in a long line of painful black superhero stereotypes—from the clumsy blaxploitation derivative Luke Cage, to lesser-known characters with wince-worthy names like Bling! and Dreadlox.

This isn’t to say there’s been no progress in the representation of black heroes over the years. As awkward as Luke Cage could be, there were good things about those comics from the beginning (as David Brothers writes). And there have been numerous other steps forward in terms of diversity—most notably the many characters created by the black-owned Milestone Comics in the 1990s. Blade in 1998 was an inventive big screen black hero who neither denied blackness nor embraced simple stereotype. And a new version of the Hulk in the comics currently is Korean-American; a step, perhaps, towards complicating the character’s racial subtext.

The superhero genre—in comics and films—still struggles to create black heroes without resorting to bland erasure or invidious stereotype. More than 60 years on, the blackface Hulk still looms over his superhero descendants, as ugly as ever. I hope Coates’ Black Panther will do at least a little to efface him.

—Follow Noah Berlatsky on Twitter: @hoodedu