Today is National Comic Book Day, but you might say there’s a dash of black nationalism afoot over at Marvel. They’ve hired white-supremacism-lamenting Atlantic columnist Ta-Nehisi Coates to write a new series featuring the 1960s-spawned first black superhero, Black Panther. Black Panther was created in 1966, not coincidentally just as a similar symbol was starting to be used by black political activists.

The comic book industry, like the movie biz into which it is quickly being absorbed, is overwhelmingly left-liberal despite its old-fashioned tropes and intense capitalist merchandising. Any time the comics industry summons the courage to send a political message, it’s a liberal one, never a conservative one. It’s taken for granted in comics industry circles that this will be so, almost without question or reflection. (I wrote a few Justice League stories and know some editors in the biz, so I think I have some idea. Obsessively reading the things like a great big nerd for decades also helps.)

If you complain about that political bent (and I don’t, really, since politics is still a marginal concern in most comics stories), you’ll increasingly hear from fellow readers who are the kind of snotty, sneering, mocking, usually white-and-male self-haters who accuse you of crying for the lost days of white supremacy (though you may have just been complaining about awkward storytelling). They’re jerks not so different from that hipster-thug guy on the streets of Brooklyn the other day seen yelling at another white guy for having too much “white privilege”—bullies who fancy themselves self-sacrificing white knights, straight outta South Park.

The feminists can be even worse, since as usual they are juggling a couple internally-contradictory positions: “Women writers must be brought in to do the kinds of stories that female readers will like!” and “How dare you suggest female readers don’t like exactly the same sorts of stories males do!” Ironically, the one consistent thread in all feminist reasoning, no matter the issue or industry under examination, seems to be self-contradiction.

Coates may do a fine job, and I don’t question Wakanda’s right to seek reparations from Atlantis after a recent war. (Will Atlantis become a biting metaphor for Coates’ similarly-named journalistic employer? Probably not.) But he’s also one of many cases of a comics industry with low self-esteem recruiting from TV, novels, movies, or now politics—anywhere but comics—to boost the credibility of comics and get some new blood. It even results in things like DC Comics’ reported new effort to emphasize non-white, non-male writers.

That may sound like pretty routine affirmative action stuff these days (complete with the usual H.R. department-style doublethink of simultaneous pride in hiring marginalized peoples and insistence that they are being hired without regard to race or gender). It is interesting, though, when such an effort occurs within an industry so directly and immediately responsive to the demands of consumers.

These companies are already desperately, transparently trying to give fans exactly what they want, in difficult financial times, and it’s likely the latest progressive outreach to marginalized peoples will last almost exactly as long as it appears to open up new markets or at least help fend off EEOC suits. If it’s win-win, fantastic. We’ll see.

If the push endures even while losing some readers or diminishing profits, many on the left would declare that truly heroic and applaud—and I’m not going to tell the comics industry what to do with its money—but to the extent this sort of thing is driven by politics, especially by fear of the law and lawsuits, it’s a little troubling to think about it having an indirect effect on the content of the culture. When you change who’s creating media, after all, you’re not just changing who gets a paycheck but (potentially) changing the resulting tone of the culture (well, maybe just a little).

Even better, the left will say! But part of the reason for the First Amendment is keeping the government from putting its thumb on the scale of culture, and it can do that in indirect ways by intimidating an industry into thinking, say, that it’d better hire more people of the sort who do stories about Black Panther’s kingdom of Wakanda being exploited by imperialists (as will likely also be the plot of an upcoming Marvel film or two), just as government can and does indirectly propagandize the populace by subsidizing non-profits and activist projects that send messages with which the government agrees.

Similarly, it’s reasonable to wonder if the comedy troupe Upright Citizens Brigade, under fire for being too white, will be less funny if it starts using people for reasons other than how funny they are. Who would argue, for instance, that comedy in the U.S. would be better off if the participation of Jews and Canadians were strictly limited to numbers proportional to their presence in the wider population?

And if social democrats out there are still inclined to say it’s not the market and customer satisfaction alone that matter, we could ask similar vexing questions even in a non-market context. Laws have been proposed in some countries that would mandate partially-female legislatures, regardless of vote totals, for instance. Is that more democratic or less?

These are subtle concerns compared to centuries of slavery, genocide, and legal oppression, of course, but ones worth mulling.

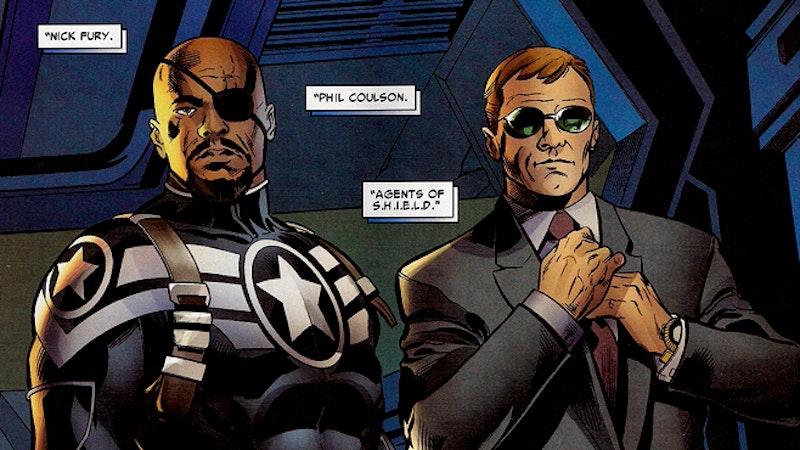

I should add that I’m decidedly not one of those fans who whines every time publishers make a formerly white character into a black or female character, etc. Like most hardcore fans, I just hope these things can be done gracefully (ideally by creating a new character once in a while!). Virtually no one complained when Samuel L. Jackson played Nick Fury in the movies, though the character had been white in the comics. To my mind, Fury was never a character whose whiteness mattered.

By contrast, turning, say, a Norse god or ancient samurai into a black man for no particular reason might be jarring—not necessarily a deal-breaker, but perhaps needlessly odd. (The multiracial nature of the Storm family in the most recent Fantastic Four movie ended up being handled with admirable subtlety and nonchalance, by the way, but tragically the rest of the movie was not good.) And sometimes when fans complain about these changes, they are right to consider them awkward and are not just being racist. Take the complex case of Nick Fury Jr., for instance.

Everyone having fallen in love with an on-screen Fury who happened to be black, Marvel decided that to maintain movie/comics synergy, Fury had to be black in the comics as well. But it wasn’t enough for them to use an alternate-universe Fury who’d always been black. They concocted an elaborate plot whereby the white Nick Fury turned out to have a black son—who proceeded to lose an eyeball and get an eyepatch just like Dad’s, then change his name to Nick to honor his father—who conveniently then disappeared.

See, this is what happens when, well, kinda dumb liberals try to do progress. Things get a bit forced and suddenly everyone who could’ve just been cruising along enjoying two different-looking, differently-descended Furies on-screen and in-print, as though race truly doesn’t matter, instead has to sit through this ethnicity-obsessive story, being made to feel as awkward as if it’s 1974 and the white neighbors aren’t sure whether it’s rude to ask what “soul food” is.

Call me #privileged, but I think there’s a lot to be said for just letting these things happen gradually and without much planning or forcing. If the rapidly growing numbers of Inhumans in the forthcoming Marvel comics and movies, successors to the mutants of old, look like a representative sample of Earth’s population, I can virtually guarantee you they will be embraced even by fans who griped when Marvel turned Thor into a woman recently.

—Todd Seavey can be found on Twitter, Blogger, and Facebook, daily on Splice Today, and soon on bookshelves with the volume Libertarianism for Beginners.