When I lived in Montana, it was easier to drive out to the abyss. If you go out far enough at night you can find a road desolate enough that it acts as an artificial border, an edge, a threshold. It’s almost certainly psychosomatic, probably just something primal activating, but you can get a surreal sensation of pure doom. It’s a cold shower on a two-lane. I’ve taken myself on journeys up these roads for years, a way to snap out of funks or kick my brain into gear. Back in Bozeman, there were two easy directions out of town and straight into the hills. Three, really. That third one was I-90 going over the pass to Livingston, too populous a road to make the trick work. There was a surface street just below it that cut off right before the mountains and ended at a Seventh-day Adventist compound that an ex grew up in, whose fenced-off elementary school also gave me spooks but not the same kind (there was some nice rolling country road out that way, but I’m sure it’s all built-up with multi-million pied-à-terres at this point), so that was no good either.

The good roads were going north towards the Bridgers or south into the Gallatins. Southwards often involved traffic—partiers heading in and out of Hyalite Reservoir or people making their way to vacation homes in Big Sky or the Yellowstone Club via the Gateway—that made it too loud, too frenzied; there was more a genuine fear or running across a drunk driver in a car twice the size of my hatchback. Reliably, cutting north out of town on Story Mill Rd. was the way to go to find the roads I was looking for, past that old grain mill by the tow lot, the one we used to smoke behind before they put the fences up. Once you got into the mountains, the road would twist and pavement would bend betwixt the tall pines. No green this time of night, only blackness would stretch out of their branches. The dancing shadows revealed by your headlights were less an absence of light and more the encroaching darkness of the woods. At some point your focus breaks with an imminent sense of annihilation. You stop the car and turn around—and you’re awake.

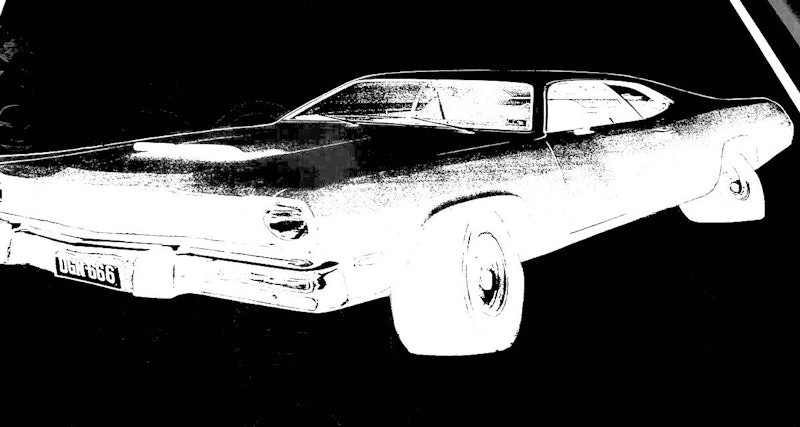

There’s an excerpt from a Michael Mann profile that’s kept popping into my head since I first read it over a year ago. As Jonah Weiner recounts, “One pitch-black night when Mann was in his teens, he drove south from Chicago to a rural Illinois back road, turned off his headlights and floored the gas pedal—hurtling, for a few crazed seconds, into total darkness.” He brings up this anecdote because of its autobiographical placement in Heat 2 as something the young Vincent Hanna did. “He’s searching, he has that crazy vibration in the nerves running through his arm when he’s 18, saying, I’ve got to get the fuck out of here, wanting to move and go places and do things,” Mann says. Weiner reads this as a “restless ambition,” but there’s more to it than that: there’s an ecstasy to that kind of action, a release. Perhaps it's not dissimilar to a 19th-century Romantic’s idea of suicide, although they didn’t have either the imagination or technology for this. It’s not the death drive of the Futurists or early modernists either, where they were as interested as the leaking oil scalding your skin in an overturned car as they were the notion of speed itself.

The other night I was weaving my way through the manored neighborhoods heading north out of Baltimore. It was the kind of rain whose icy needles prick your skin as it flows across you. I was on a spare tire, taking it slow—gentle on the brakes, easy on the clutch. Wouldn’t want to spin the 20-year-old rubber at a light or lock up coming to a stop, especially if ice was on the horizon. Taking it up Charles St., past where it feels like a natural artery and into a vaguely county byway, where it splits off and you never know if you took the right turn until you’re miles past your destination. That is, if there is a physical destination in mind. For me it's much easier to find the sensory one. Suddenly the road turned black. Pitch black, absorbent. I switched the wipers to a constant wish-wash to prove I was sure of what I was seeing: the road in front of me had disappeared. I lifted off the gas and waited for the car floating on the nothingness in front to vanish behind a bend before I turned my brights on. There was no road, no asphalt, only a void between metal-beam guardrails and those tall, consuming trees. I suddenly felt awake, alive, and turned the car around.