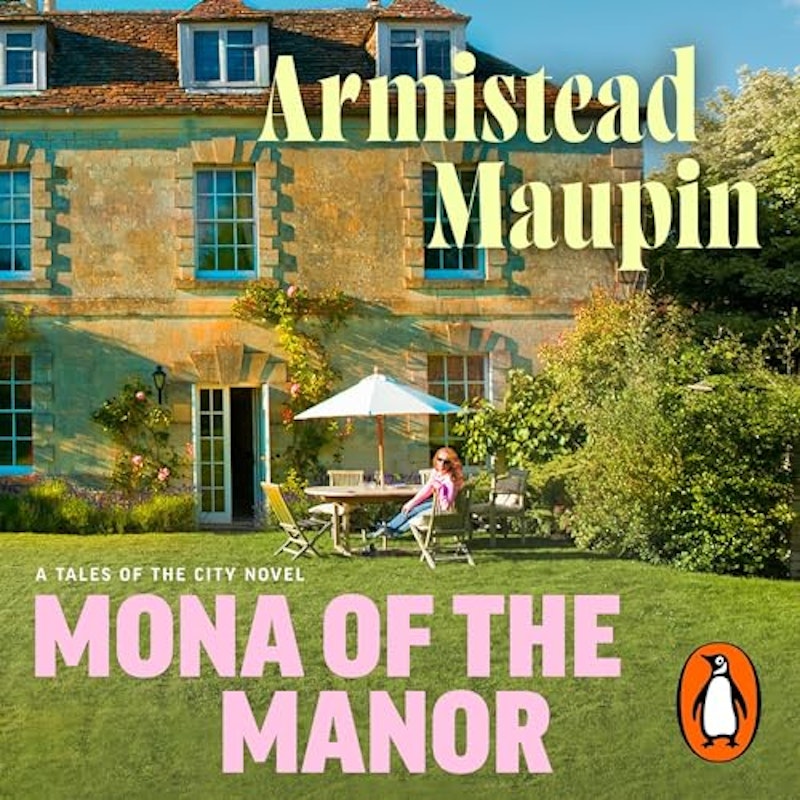

For many fans of the Tales of the City series, reading Mona of the Manor will be like visiting a best friend from your youth, now diminished by senility. Like watching a resurrection of a favorite TV show—say Frasier or Sex in the City—that’s often an embarrassment of the original. It’s ironic that the 10th installment of Armistead Maupin’s Tales of the Cities, Mona of the Manor (HarperCollins, March 2024) should be set in one of the grandest, if somewhat derelict, manors in the Cotswolds. It could be that Maupin never bought a home in his adopted city of San Francisco, and now in interviews complains that he could no longer afford to do so. The blurb on the ninth of the Tales series, The Days of Anna Madrigal, reads: “The ninth and final novel in Armistead Maupin’s classic Tales of the City series… is the triumphant resolution of the sage of urban family life….”

Apparently 11 best-selling novels (the previous nine Tales of the City, with six million copies in print, plus the unrelated Maybe the Moon and The Night Listener) plus a Channel 4/PBS series, a Showtime series and a Netflix series didn’t pay enough for Maupin to buy property in the Bay area (though he did buy a home in 2012 in New Mexico and lived in it for a year or so before moving back to rent in California).

Mona doesn’t move the tales forward in time. Anna Madrigal, the den mother and landlady to the menagerie of characters Maupin created in the Tales, dies at 93 in the ninth book, and in this 10th book, she’s alive, 73, and visiting one of the main characters, Mona Ramsay, who hadn’t yet had a story with her name in the title (after the first six “ensemble cast” novels, Maupin went 18 years before he produced Michael Tolliver Lives, Mary Ann in Autumn, and The Days of Anna Madrigal). The Tales span over almost four decades, beginning in 1976, but Mona’s set before the repeal in 2003 of Clause 28, a British law that prevented local governments from using tax dollars and government resources to promote homosexuality, about which Maupin likes to have his characters complain.

The plot’s a little thin. Mona Ramsay, one of the original Madrigal tenants, has inherited a title and Easley manor after a green-card marriage to a British Lord who wanted to be an American so he could stay in San Francisco to have a complete gay life. After Lord Teddy dies of AIDS (a common fate of Maupin’s secondary characters), Mona runs the manor as a B&B, at some point adopting a half-British, half-Australian aboriginal gay teenager, Wilfred, to prevent his deportation. Mona fights with her on-again, off-again almost girlfriend, the local Post mistress, over whether men who think they’re women should be able to use women’s spaces (e.g. restrooms). An ultra-conservative North Carolina couple, Eddie and Rhonda Blaylock (Maupin’s parents and he were friends and segregationist supporters of Jesse Helms during his early years in Raleigh, which seems to lead Maupin to need to prove perpetually his progressive pedigree), book a room as part of their European vacation. Anna Madrigal and Michael Tolliver come from America to visit. At some point the closest thing to a plot is that Mona and Wilfred help Rhonda leave her physically abusive husband. And then there’s a murder and a coverup. I wonder if Maupin thinks a screenwriter can rework this as a murder mystery for cinematic payoffs.

Philip Hensher’s review of how the first of the four “late” Tales books didn’t live up to the first six remains spot-on for Mona of the Manor as well: “The six Tales of the City novels are sweet, amusing period pieces and their main appeal is a pastoral one. They describe, in the late Seventies and early Eighties, a haven of liberality and sexual freedom which… worldwide readers dreamt of escaping to. The sad truth is that everywhere now is a little bit like San Francisco, with internet dating, amateur strip nights in bars and, if you want it, casual sex in sex clubs. And now the San Francisco culture is here in our own cities, it turns out to be not quite as adorable as it seemed in Maupin's books… The charm of the series was always one of escape; in this sad and unappealingly thin book, what we discover is that the pleasures of Arcadia are pretty much like the pleasures of Clapham. That's honestly not what anyone wants to hear.”

In Maupin’s autobiography, Logical Family, we learn that a lot of the charm of the early Tales books was due to the editor of the San Francisco newspaper that first published them as a serial. Before Maupin became famous as a gay activist and AIDS crusader, he was constrained by his employer to keep his serial from being too gay. His editor kept a board showing the number of gay and straight characters who had appeared in the Tales, and how much time they were getting. The constraint was to keep the gays at no more than one-third of the dramatic personae. According to Maupin, he spent a lot of his time, including excessively long lunch hours as a young style section "reporter," in bath houses and at orgies, and may have only kept his job because his serialized story was such a hit. His editor basically commanded him to write about what he didn’t know.

It looks like this regimen may have been good for Maupin, kind of like the rules for haiku. It forced him to be inventive with a variety of characters and a complexity of their interactions—a blackmailing tenant with an ugly secret, a cannibalistic religious cult, a parent who tracks down a long-lost child, a fashion model pretending to be another race—and not just produce lighter more comical versions of John Rechy stories about gays in parks and bathhouses. It’s clear that Maupin can do it if he wants to. His 1992 novel, Maybe the Moon—the slightly biographical story of Cadence Roth, a dwarf actress in Hollywood (based on Maupin’s friend Tamara De Treaux, the actress who was E.T. in E.T.)—is a richly detailed imagining of the lives and adventures of two down-on-their-luck heterosexual women who are housemates. Mona doesn’t have this same level of detail and imagination. Now that he’s kind of rich, or at least feted and famous, only Maupin could impose that discipline to get out of his own skin that his editor once imposed.