“The household itself was rather a sprawling brawling flabbergastery of virtual lascars and bonobos, headhunters and cannibals. And yet, here we are." He handed a small neat volume to Scruthers. The square-bound book had a matte black cover. In burning orange type: "Decompositions" by Tomás Esperanto. It smelled new because it was new, fresh off the press, almost warm. And warm was this July eventide.

Scruthers opened it, scrutinized a bit, scrunching his brow to feign more interest than he could actually muster and said, "Interesting."

Practically hopping foot to foot, Tony Welsh continued, "Yes. Amidst the chaos of his young life he managed to cobble together these poems, brilliant in my opinion. Scalding, transcendent, sublime, incandescent. New directions, new methods! Open the window and let the 20th century in!”

"Hm," hummed Scruthers. “Indeed. Mine to keep?"

"Of course!"

"Thank you," he declared while inwardly groaning. Now he'll have to read the avant gibberish, the so-called work of a, no doubt, beret-topped weird-beard. Well, all part and parcel of being a poetry critic. And all part and parcel of being a friend to Tony, he the beneficiary of a small trust that allowed him to pursue his hobby of bookbinding and publishing, almost making it a profession. Nice work if you can get it.

Tony Welsh usually printed exquisite (if slightly twee) volumes of works in the public domain: Poe, Shakespeare, fairy tales, with old woodcuts or such serving as garnish illustrations. It gave him a place and a purpose, a sense of pride as the books were highly regarded in certain circles. Once in a blue moon, he splurged and paid someone for a new work. In this case, Mr. Esperanto was the recipient of his grace.

Upon returning home, Aldon retired to his office and opened the book for a perusal. The first poem, like all the rest, was entirely in lower case, and was a stranger to such niceties as punctuation or, even, titles. With dread he read:

voices of children float

through

music mosaic

the way light moves

through

dense copse

at midday

threw

dance corpse

on midway

the singer is working

Aldon Scruthers pinched the bridge of his nose and winced. "At least there's a stab at rhyme. More than one can usually hope to expect from one of these motley holy-moly barbarians. If he keeps revealing such dangerous symptoms of tradition he may be drummed out of the beatnik brigade, shoved naked from the garden of illiteracy."

Regardless, Aldon was compelled to review it; he owed as much to his old friend and their GI days in the Pacific. But he'd rather face Jap bullets and bayonets than plow through this minefield of verbiage.

Aldon Scruthers managed to keep a roof over his head churning out poetry reviews for the Branville Crier (which also hosted his bridge and chess columns) and for a long list of small magazines, sometimes using the pseudonym Aloysius Crouton. It will be with said alias that he'll find something to say about this bohemian book. And that something will be a tightrope act of keeping it noncommittal whilst seeming to commit. (These are the times that try a man's soul, truly.) It will have to be for one of the pinko rags, one that hasn't quite decided whether or not the unwashed hirsute armpit-scratchers of Greenwich Village are strange visionaries or merely the detritus of decadent late-stage capitalism.

Aldon considered delving deeper into the derangements of "Decompositions," but paused to pour a large tumbler of sherry. After a generous gulp or two, he decided he was more in the mood for some blaring Dixieland jazz. Tomorrow for the ordeal. Tonight? Let the jazz, the good jazz, rip!

Aldon dwelt in a small bungalow on the outskirts of Branville, a provincial New England town that was home to Branville College, an institution that was provincial in spades. If nothing else, its existence guaranteed local bookstores, and if push ever came to deadly shove, he could (shudder) teach.

The following morning, fuzzy from last night's libation, Aldon exited his domicile, blinked and squinted at harsh daylight and strolled into town intent on a bacon and eggs breakfast. On Main Street, approaching O'Brien's Diner, he happened to bump into his favorite living wordsmith. Aldon doffed his fedora and made a slight bow. "Always a delight, Miss Anne," he purred.

"Oh, Aldon! What a joy to run into you! A day without Aldon is like a day without sunshine! How are you, my good fellow?"

Anne Thrope, the poetess whom Aldon held in highest esteem, was little known outside of New England, and not even terribly known within New England. But she was a star to a few in Branville. Aldon knew her to be of a superior if, alas, antiquated breed. He decided to forego breakfast for now, and use this opportunity to escort Miss Anne home, just a few blocks over to her family manse, a two-story ivy-covered affair, pre-Revolution, as were her ancestors. Once there, she invited him in for tea and crumpets.

Over the repast they spoke of Shelley and Byron, always back to Shelley and Byron. And as was customary to their discussions, the duo switched languages midstream every 10 minutes or so, commencing in English until one spoke in, say, Old English before the other eventually responded in German, then onto French, Latin, Greek, Arabic. Before long it was late in the afternoon and both were a trifle exhausted, but in a good way, a haze of contentment suffused each of their beings. Aldon excused himself to be on his way.

Feeling refreshed and invigorated as he sauntered homeward he thought about how 'twas always time well spent with Miss Anne and her penetrating insights into poetry, as well as her trenchant views on the rising tide of the riffraff.

Once home, Aldon popped a chicken pot pie into the oven and poured a small glass of sherry. While his dinner cooked, he made another attempt to machete through the thicket known as "Decompositions. The second poem read:

roses are poses

and

sometimes

are red

sometimes are

white and

sometimes as blue as

blazes in this

aberration of an

electromagnetic stereo-phonical

hi-speed

lo-brow existence i wish

it would rain

In deference to his old friend, a friendship forged in battle and blood far from home, Aldon refrained from winging the book out the back door and into the woods where it could rot in peace. Instead, he placed it very gently at the bottom of his socks drawer. He'd read entirely enough to be able to counterfeit some sort of review. Any further reading would interfere with the enjoyment of his pot pie in particular, and life in general.

That evening around nine, Aldon hopped into his MG, took it for a spin, the top down on this sultry July night. Outside of town, at the light before the highway, a souped-up jalopy jockeyed up, it piloted by a side-burned delinquent. "Race, pops?" Aldon gave a curt nod. As the light flashed green, both drivers stepped on the gas. Aldon allowed the pup a slight lead before he gave the gas pedal a small press, passing the punk with ease. He knew this would bait the nitwit, further knowing there was little chance the inexperienced knucklehead in that bucket of bolts would be able to negotiate the upcoming curve.

Sure as shootin', the hot rod's tires screeched, lost their grip, the car careening across lanes, off the road, airborne, smack into a massive oak, bursting into orange flame against the black of night. Aldon shook his head and eased off the pedal. Chin raised, he smiled and muttered, "Ah! The gene pool improves. Hopefully, he left no spawn to burden us. If I could only do the same to one Tomás Esperanto. And his ilk. Well, if wishes were horses, et cetera."

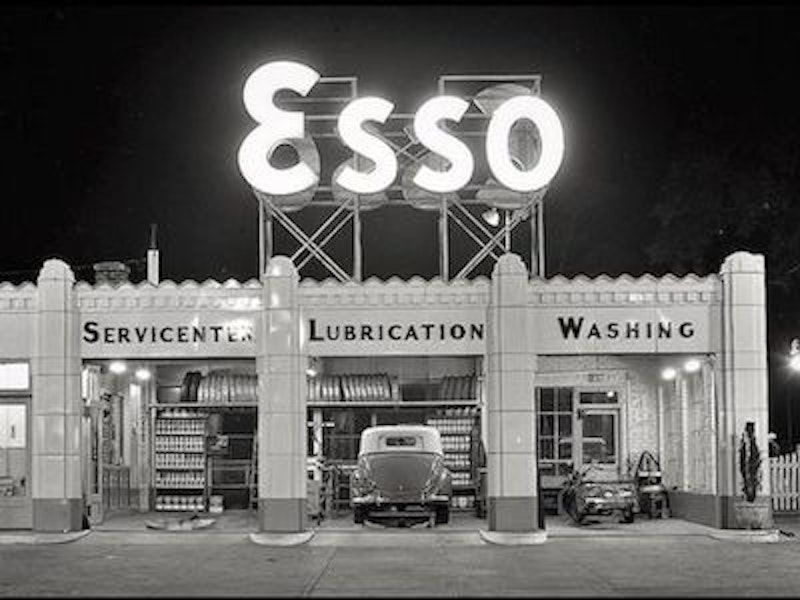

About a half-mile ahead, he pulled into an Esso station and parked, left the motor running. At the pay phone, he dropped in a coin. "Operator, would you be so kind as to connect me to the Branville police? Yes, I should like to report an automobile... accident."