I’d just finished Jay McInerney’s latest novel, Bright, Precious Days—a clunker, studded with NYC clichés—last Saturday morning when I joined the weekend mob at Baltimore’s Old Bank Barbers in Hampden. Old Bank’s a first-class joint for a haircut, but it’s vexing, given the perpetual weekend crowds, that the order of customers is willy-nilly. The trains don’t run on time here, though it doesn’t appear to cause much consternation. I mentioned that to the fellow next to me, who said, to my conditional amusement, “Why don’t you play the senior citizen card, just go to the next available chair. No one will stop you.” I looked him at quizzically, even though I probably was the only one there with white hair, and said, “Hmm, looks like you’ve got a lot of rings around your own trunk, buddy.” He laughed, admitted that was so, and we got on.

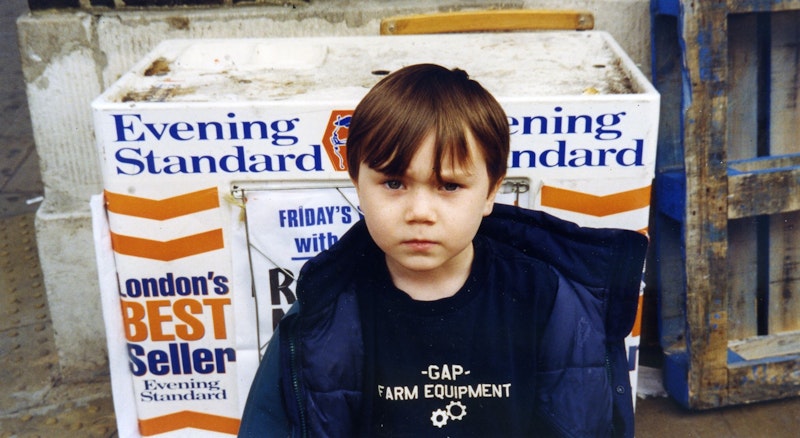

Forty-five minutes later, I walked to the nearby 7-Eleven—where Citibank has an ATM—to deposit a couple of checks. My son Booker (pictured above in 2000 in London), is in Europe now and in the past he’s helped me negotiate this very confusing process (I’ve parked money in Citibank since the 1980s, but they pulled out of Baltimore last year, which is a pain in the neck.) It was a pickle: the sun was glaring on the machine, and the instructions were not entirely clear to me, so I fumbled around until a young man very kindly came to my assistance. I don’t suppose it was entirely altruistic, since he was next in line, but my appreciation was sincere. I read a story in The Daily Signal today, detailing a “shock poll” that showed 32 percent of Millennials believe George W. Bush was responsible for more deaths than Joseph Stalin, which I guess isn’t surprising, although it’s not quite kosher to single out these youngsters since most Americans across demographic lines would be hard-pressed to name more than two Supreme Court Justices, let alone any Cabinet members. But I bet my helper at the ATM is not included in that group.

By the way, this isn’t an indictment of my fellow Baby Boomers as a whole for failing, like me, to take the time and adapt to a changing world of commerce. That said, McInerney, 61, is stuck in a hell of a rut, apparently unable, unlike other aging authors, to produce a book that’s contemporary. Before continuing, I did like one passage, in which he describes quasi-protagonist Corrine Calloway (McInerney’s third book centered around Corrine and her husband Russell) seeing her downtrodden spouse further down the subway car she was riding, and getting a start at how old he suddenly looked at 52. “[S]he was shocked by his slumped comportment, his slack demeanor, even by the gray in his hair… He looked like one of those exhausted souls she saw every day on the subway, men she imagined stuck in jobs they hated… swaying with motion of the car.” It happens, Corrine and Jay, most people aren’t as spunky as they were in their 20s. McInerney, at least judging by his book jacket photo, looks fine, but he’s lost his way as well, at least in his profession.

I’ve admired many of McInerney’s books—despite the unavoidable tabloid fodder about his personal life, which began after his brilliant 1984 debut, Bright Lights, Big City—and was looking forward to Bright, Precious Days despite the ominous cover, which, like his debut novel, features a shot of Tribeca’s Odeon. But it sputters, another examination of affluent and powerful Manhattanites who became unraveled during the 2008 economic crash, as if Michael Lewis hasn’t already had the last word on that subject. What’s worse is that McInerney writes as though it’s 2007, stuck in his own time warp, although I’m guessing that he lives high on the hog and needed the paycheck to support that lifestyle.

The following excerpt is so dated, so trite, that it’s an easy target for parody if anyone were so inclined, which I don’t suppose they are. It’s akin to some really bad New York magazine writing—another vestige of the 1990s that’s “slumped” and “slack.”

Once again it was the holiday season, that ceaseless cocktail party between Thanksgiving and New Year’s, when the city dressed itself in Christmas colors and flaunted its commercial soul, when the compulsive acquisitiveness of the citizenry, directed outward into ritual gift giving was transmuted into a virtue and moderation into a vice… Doormen were suddenly eager to perform their jobs, opening taxi doors and carrying shopping bags, which were abundant, and maîtres d’hotel greeted their regulars with extra obsequiousness.

Even though this passage takes place pre-crash, by 2006-07, much of the glitz McInerney describes had become an anachronism—even if financial swinging dicks were publicly crass in displaying wealth—for the city was already getting a facelift, becoming more generic as independent stores failed due to Internet shopping. And it’s surprising that McInerney, entrenched in the publishing industry, doesn’t note that that world was heading toward collapse.

As for the rest of the novel, the plot twists are predictable, the bittersweet conclusion obvious and the concentration on “ladies who lunch,” trophy wives, $4,000 bottles of wine consumed by gauche consumers, and endless chatter about “foodies” is redundant.

Maybe McInerney was too engrossed in writing his own (embarrassing) wine columns, so he missed the plain fact that in the late-aughts there were no longer any Masters of the Universe.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955