With the re-opening of Chumley’s on Bedford Street this week after an over nine years’ absence, I thought I would talk about some of the older “gin joints” around town. There are a couple of dozen in New York City that go back as far as the 1800s; I’ll discuss a few of them here.

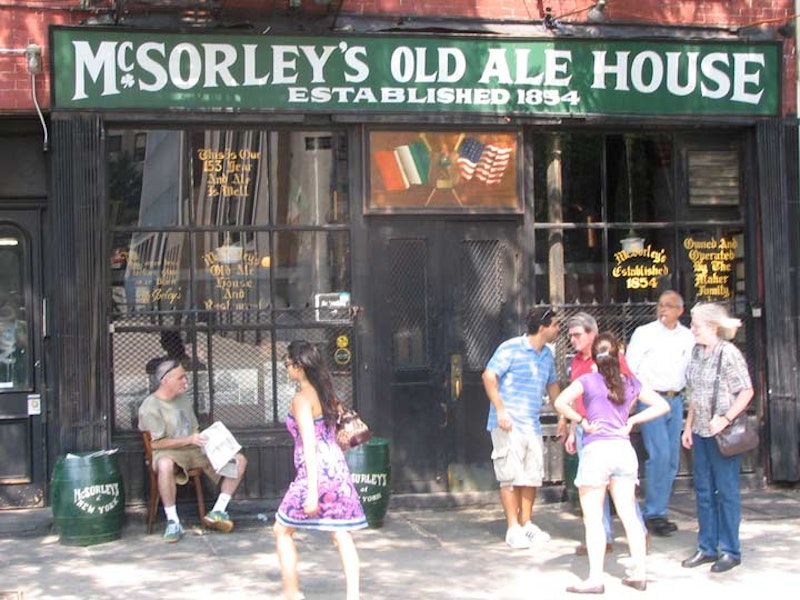

Though McSorley's claims it opened here on East 7th Street east of 3rd Avenue in 1854, the late NYC historian Richard McDermott's research, employing old insurance maps, census data, and tax-assessment records, indicates it opened in 1862. In any case, it's pretty darn old. The later opening date would negate claims that Abraham Lincoln stopped in when he gave a speech at Cooper Union in February 1860. There are hundreds of pictures on the walls; customers have brought them in throughout the decades, and the staff usually finds a place for them.

In The New Yorker chronicler Joseph Mitchell's era, McSorley's used four soup bowls for change in lieu of a cash register, one each for pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters. The coal-burning stove is still there, as is the safe, the rack of corncob pipes, and a set of turkey wishbones hung on a light fixture. The tradition dates to World War I when soldiers going off to war would hang them there. The ones that came back removed their wishbones. Until recently the wishbones had accumulated a thick layer of dust—they were never cleaned until health inspectors forced the ownership to do so.

McSorley's famously did not admit female patrons until the summer of 1970. At first the bathrooms were unisex until one of the kitchens was converted. But the old place still looks like a woman never set foot in it, until you look around and notice that women seem to be about 60% of the patronage.

Chumley's is probably the only major bar or restaurant in New York City that has never had a sign or marking of any sort on its exterior to mark its presence. Yet most Greenwich Villagers know where it is, officially 86 Bedford Street just north of Barrow, and most nights, it's packed.

Chumley's building dates to the 1830s and was originally a blacksmithery. According to legend, in the pre-Civil War era it was a stop where escaped slaves could find a haven (there was a black community on nearby Gay Street). At length it became a gathering place for leftist radicals. By 1922, Leland Chumley had established a speakeasy/gambling den in the old building; the tradition of not marking the entrance continues to this day.

During and after Prohibition Chumley's became one of NYC's many literary hangouts. The difference here is that the authors' original dust jackets, and their portraits, line the walls of the place on all sides. You will find just about every big name in 20th century literature here from Hemingway to Mailer to Ginsburg on the wall.

According to legend (which party pooper McDermott disputes) the term "86 it" for "kill it" or "forget about it" comes from a warning the cops would give, phoning ahead to Chumley to let him know they were on the way and customers should "86" or book out the entrance/exit.

Way back in 2006, a celebration for the release of Forgotten New York the book was held at Chumley’s (that’s me rattling on in the center in the photo), and some months later, the roof collapsed, an event that wound up shuttering the place for the better part of a decade. It reopens under new management this week.

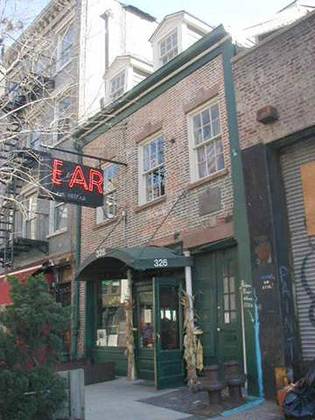

The Ear Inn, on Spring Street near Washington, is located in a house built by tobacco trader James Brown, who, according to legend (again) was the black man pictured in Emanuel Leutze's picture of Washington Crossing the Delaware. By the 1850s, the place was a brewery in which drinks were served to local stevedores and dock workers; it more or less filled that function for the next 150 years and counting. Landfill gradually distanced it from riverside.

The neon sign dates to the 1940s; in the 1970s, the owners painted out half the "b" and presto, the Ear. Like many of NYC's oldest joints the Ear is lined stem to stern with ancient photos and memorabilia.

When your webmaster was young many, many years ago, I frequented the Old Town Bar on East 18th Street between Broadway and Park Avenue South, especially during the summer. The beer was ice cold and the air conditioning was even icier, just the way I like it. Like McSorley's, the OTB looks pretty much exactly the way it must have when it opened here in 1892. Opened as Viemeister's that year, it still has its original tile floors, pressed tin ceilings, beveled glass cabinets and light diffusers, wood bar and booths that have hidden compartments to store drinks while the coppers raided during Prohibition.

The White Horse Tavern is another of NYC's long-lived literary hangouts, and yet another with an ancient neon sign. It has been here on Hudson Street and West 11th since 1878, replacing the James Dean Oyster House. And one of the White Horse's patrons was indeed too fast to live and too young to die.

Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) was born in Swansea, Wales and surprisingly enough, did not visit the USA until 1950. Thomas first came to prominence as a poet with Eighteen Poems in 1934; his most famous work is perhaps "Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night." His prose works include A Child's Christmas in Wales and the play Under Milk Wood, both published posthumously in 1954.

It's a conundrum that has lasted throughout the centuries: why are so many of our most creative individuals given to dissolution and self-destruction? Thomas, the story goes, drank himself to death at the White Horse in November 1953, but the story is more complicated than that: the writer had been quite ill that year, and a number of factors likely contributed to his demise.

A visit to the White Horse today provides a relaxed atmosphere, especially in the front room where you watch the Village go by out the window. Check for how many representations of white horses you can find!