Neil Gaiman’s 1996 novel Neverwhere has been chosen as the novel everyone in Chicago is supposed to read for the One Book, One Chicago program. So what the hell; I’m in Chicago. I did my civic duty and read it. And having finished it, I was left with a question. Why?

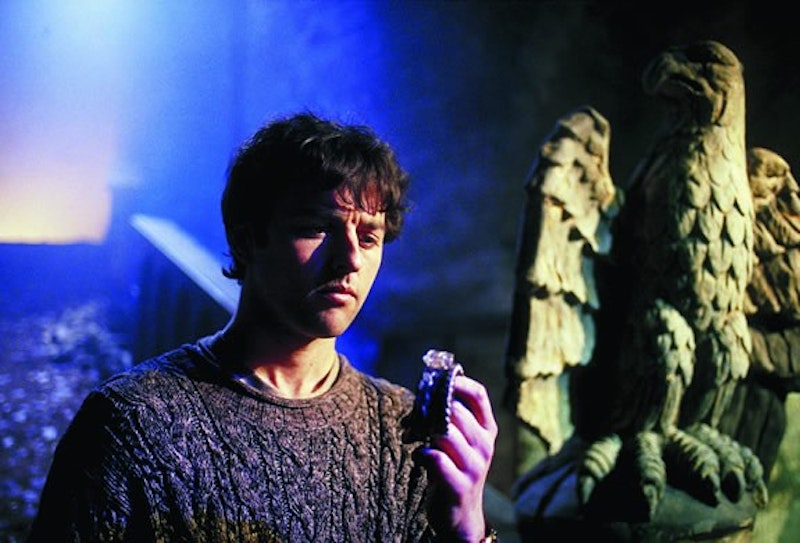

I’m sure Gaiman’s novel made sense back when it was released. It was a novelization of a Gaiman-penned BBC series, first of all, and novelizations make sense, if by “sense” you mean “dollars and dollars.” And besides, it’s always the right time to release standard-issue genre product. Richard Mayhew is a rumpled but/and appealing Londoner with a mundane job and an overbearing fiancé. Then he is pulled into the mystical magical world of London Below, therein encountering an attractive damsel in distress and quests and beasts and, well, you know the drill. Richard goes down into the down below and discovers within himself Hidden Depths. As a reward, he gets everything he ever wanted in his mundane existence—promotions, perfect wife, etc. But he turns it all down to go back to the magic world because he is no longer the mundane yob he once was but a big fat hero. Yay!

So as I said, at the time it made sense. People read narratives like this at a brisk pace; the supply must be replenished. Gaiman churned one out, it was consumed and everyone was happy. Fair enough.

But there are a lot of books in the world, and even presuming that One Book, One Chicago has to pick a couple of them a year, so perhaps they’re running out—it’s still hard for me to figure out what made Neverwhere stand out. Even though my local Borders just went belly up, I bet I could still sneak in by a back door and find, amidst the scattered boxes and debris of the inglorious retreat, at least a dozen volumes scattered about forlornly in the urban fantasy section that are indistinguishable from Neverwhere.

I guess there are various possibilities. Maybe somebody on the selection committee is just a huge Gaiman fan. Maybe it’s linked to the stage play of Neverwhere, which is supposed to be opening in Chicago—synchronicity and all that.

Or maybe (and this is my favorite theory) the appeal is the book’s bizarre lack of sex.

Urban fantasy is a fairly eroticized genre: at this date, post-Twilight, it’s a hybrid of fantasy/horror and romance; all heaving angst and tortured bosoms with time out for fairies. Gaiman’s book is considerably more chaste while still being basically obsessed with throwing shapely lasses our hero’s way. It’s got the tantalizing tingle of lust without ever admitting its baser instincts (which might raise unfortunate questions in the minds of the censorious.)

Whether or not this played into the selection, there’s no doubt that, as far as love and women go, this book is a marvel of bad faith male fantasy. Almost the first thing we learn about Richard Mayhew is that he “had a rumpled, just-woken-up look to him, which made him more attractive to the opposite sex than he would ever understand or believe.”

Richard is rumpled, attractive, and humble. On the strength of those qualities, and those basically alone, we are to love him, especially if “we” are women. The narrative proceeds to throw at him girl after girl: Door, the pursued heroine; Hunter, the sexy lesbian leather-encased bodyguard who takes a pronounced liking to him; Lamia, a goth hottie, and Anaesthasia, a young girl who guides him about for a few pages.

Richard never gets anywhere near consummation with most of these women; his clueless continence is why they all look upon him with such proprietary longing. The exceptions are instructive though. He sits on a bench with Anastasia beside a hot-and-heavy couple who (magic!) can’t see them. Shortly thereafter, Anastasia gets killed, allowing Richard the opportunity to soulfully mourn her and erase that pesky hint of uncomfortable eroticism. In another incident, the goth hottie Lamia actually kisses him—and she then turns out to be a vampire, suckling the life out of him like an evil inverse mommy. Sex is death! (Though maybe not an entirely bad death; there are a couple moments in the book where Richard seems a little nostalgic for the vampire and what she was offering.)

The one woman Richard actually does sleep with (always off-camera and in memory, but still) is his bitchy, high-powered girlfriend Jessica. Jessica has numerous sins. She drags Richard to art galleries and drags him shopping and wants to make something of him. We are supposed to despise her for this, though, really, it’s hard to see how one could not want to make something of Richard. For he is, in all his attractive, slumpy glory, about as boring a character as I have ever encountered in literature. If he has ever had a single real interest or thought or passion, Gaiman does not allow said interest, thought, or passion to disturb the still perfection of Richard’s rumpled vacuity. Richard does collect little troll dolls, it’s true—but Gaiman takes pains to inform us that this is largely accidental, and has nothing to do with a real interest in troll dolls. Richard’s only actual attribute appears to be a kind heart. In the absence of any personality, though, it’s hard not to see this as tacked on.

Anyway. The point is, Jessica wants to change him, and that is wrong, wrong, wrong. And so we have Neverwhere, the entire purpose of which is to pry Richard from those predatory, improving arms; to make Jessica break her engagement with him so he can leave Mommy and grow up…or never grow up, as the case may be. And so London Below opens up and takes Richard in, offering him a teasing erotic smorgasbord and the adrenalin high of conflict. And when he returns, Jessica comes crawling back, begging him to be her fiancée again, so he can dump her. With sadness, of course, and delicious superior regret. Paid her back, the bitch—and he was even sorry about it!

At this point, you’d think Richard would celebrate maturity by going out and screwing someone. Someone is offered (she’s from Computer Services)—but no. Not that life for our boy. Instead it’s back to London Below, where, presumably, more exciting adventures and more chaste eroticism await. Richard’s a rumpled, drab Peter Pan; Neverwhere is Never-Never Land with the spark of imagination swapped for very slightly more sex. It’s a poor trade, but maybe it’s what Chicago is clamoring for. How should I know? I just live here.