I’m pretty much of a recluse. Every now and then I try to break out, and I discover it ain’t so easy. Things happen.

For example, I volunteered at a local meals-on-wheels operation. I’ll call it the Caravan. It’s a good operation, as far as I can judge, and the place ran pretty much okay. But if you’re like me, everything comes with anxiety. So I was anxious whenever I went to Caravan. Signing up was a big decision for me: I was taking a stride into a different sort of life, one with people in it. Once there I worried about passing. Was I dicing the carrots the way carrots are supposed to be diced? Did I look too long at the dark, pretty girl from Australia? And was I keeping up? Look at all those meal trays waiting for lids.

I lasted about six weeks, two shifts a week, most often Wednesday and Friday mornings. I did all right. Kitchen work isn’t complicated and I was willing, and my boss wanted everyone to be happy. Ellie, as I’ll call her, was a nice girl: rosy-cheeked, bear-shaped and pretty. She had the effect that gentle, pretty girls, even bear-shaped ones, produce on men. One time I cut my finger and she told me where to get the bandages and antiseptic. After she did so, and before I went off to do the washing and bandaging, I held out the finger for her to see. Why? I don’t know. It was automatic.

My boss listened to folk music and wore flannel shirts and old corduroys. The corduroys were so old that they hung off her, and the effect was nice but not sexy. Or else, if it was sexy, it was sexy in a way that somehow also allowed you to feel comfortable, which typically is a reverse gear to sexiness. At any rate, with Ellie in the corner of my eye I felt like I was standing in woodlands, a Disney forest arrangement—co-op land. Fresh, simple beings pursued existence as they wished.

Maybe, summers ago, Ellie had worked at a real office long enough to know how to work the Xerox machine. Since then, freedom—back to her natural environment, co-op land. She was innocent like a woodlands creature, somebody who was so much a type that she couldn’t think about the why behind anything in her life, or behind anything else. She was naïve and it made her endearing. A typical Ellie remark: “I guess the legacy of colonialism would have something to do with that.” Talking about The Wire one time, she said she had trouble with the dialogue. Why? “The characters are all American,” she said. Then: “… from Maryland.” Because she couldn’t say the word black.

I stayed anxious, as always, but life moved along. On my ninth or 10th visit I looked around and it hit me: the customary feeling of my week was no longer what it had been. On Wednesday and Friday mornings I was here, one place in particular, and just a little while before my life had not been like that. So for a couple of seconds I stood there and noticed the difference. I don’t say this was a big moment, but it was the only such moment I’d had for six or seven years.

A few sessions later and everything caved in. I never actually quit Caravan, but I abruptly stopped going. I had made Ellie mad, she of all people—what a twist. Yet, all along, I had assumed it could happen. If you’re anxious on the job, most likely you’re anxious about some boss somewhere, and she was the only one in sight. So the ground rules of my life allowed for the abstract possibility that this girl might blow up, and the ground rules turned out to be correct. Or it goes deeper than that. My underlying ground rule: Catastrophe is always possible. That belief is automatic for people who worry a lot about passing. You can always be found out, and being found out is always a disaster.

Yes, most of my sessions went fine. But toward the end Ellie was getting a bit outgunned by her responsibilities. She had had to hurry to meet deadline, and she got peevish. On my next-to-last shift she thought I had miscounted tray lids. “Looks like somebody …” she said, an aside. Then, half a minute later: “… Oh. Okay, that’s all right.”

On my last day, as it turned out to be, I did something kind of stupid, which was to attempt bantering by myself. I liked to joke around with one of the other volunteers, a cheerful, live-wire Native kid who had come down from a reservation up north to go to school; he worked at the kitchen because he got course credit. Ben told jokes from the Harold and Kumar movies and asked me whether I thought Daredevil could beat Spider-Man. But he wasn’t there that day.

Standing over my carrots, I murmured a commentary to myself, something bouncy and pointless. The two other volunteers didn’t seem to mind—I was quiet. But it must have been like hearing one side of a cell-phone conversation, and Ellie was having trouble with her deadline again.

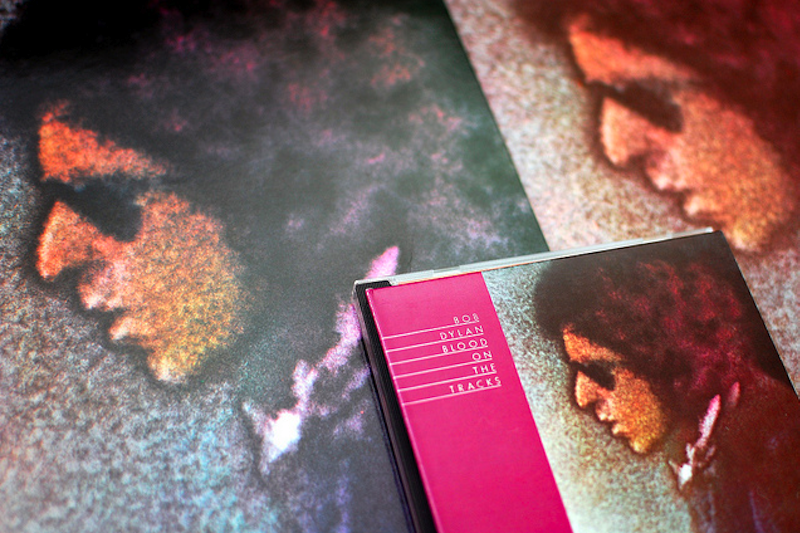

“Boy, this station plays nothing but Bob Dylan,” I said, more or less to myself. It had been playing one Dylan song after the other.

“That’s my iPod,” Ellie said. I asked her if she had Blood on the Tracks. I wanted to find common ground. But Ellie stopped cooking and stared at me. A long few moments passed before she answered. “No,” she said at last. “No, I don’t.” Her mouth was hanging open, and I had no idea why. I felt like somehow, without my hands going anywhere at all, I had slapped her.

Bosses can be rude, and it turns out she could be too. For the rest of the shift she snarled at me. They were baby-size, amateur snarls, but it’s the thought that counts. “Water is a finite resource!” she snapped at one point—I’d been splashing around with the dishes. When it came time for me to leave, Ellie mustered up a smile, seemed about to say something, then didn’t. “Bye,” she said at last. I had already announced that I was off to the U.S. for a few weeks.

That afternoon I took my usual walk on the mountain and it occurred to me: Blood on the Tracks … blood on the tracks. A bit later I saw William, my building’s crazy janitor, and told him my suspicion. Ellie had thought I meant menstruation, I said. William, as usual, was squawking and indignant. (He’s in his 60s: a failed intellectual, a character.) “You’re insane for thinking that,” he said. “And if you’re right, she’s insane too, and you’re still insane for guessing that’s what she thinks. The whole thing is sick, it’s crazy.” And so on.

He ought to be right. In this world there should be no way that asking your boss about Bob Dylan can turn into a communication about menstrual issues. But that’s not the world we live in. We live in a world of disasters.

The way I see it, I gave something away. I asked Ellie about my second-favorite Dylan album, and in doing so I let something slip. What? If Ellie was crazy enough (in William’s sense) to read some hidden meaning into Blood on the Tracks, I can only hope she was crazy and wrong, not crazy and right. But I don’t think I had anything in mind. My secret was just that I wanted to pass, and I was found out because that’s my nature.