The office window that won’t open looks down onto a tempting stretch of wide river. You’re never explicitly told why it doesn’t open, and I’ll leave you to draw your own conclusions. The office itself is out of town, in the middle of nowhere; an industrial park devoid of shops or city people. Most workers drive to it, and park on a glossy, tarmacked field that charges by the hour, and rolls onto a soulless 24-hour gym. Coffee shops, or a “thriving riverside scene” appear to be some years away. And this is despite the hopeful protestations of oleaginous middle managers, who, like untrusting estate agents, casually talk up reasons for the out-on-a-limb location, during strained encounters along corridors, or in nicotine-breath elevator spaces.

Such riverside reincarnations may have happened in other places, but it hasn’t happened here. Instead of soya-milk flat-whites and fizzy waters, here a cold and stinging wind flicks your ears as it barrels down the brown-rippled river, and smacks slap-bang into the glass-plated, box-shaped construction, that we all call work.

It flows both directions according to the tide, I heard the strained voice of a colleague explain one day on the fourth floor, as he attempted to sound interesting and approachable to newcomers.

“Tide?” repeated one of the new starts.

My heart sank. The vacancy on his face suggested he was serious.

The new guy, let’s call him Sand, genuinely had no idea about tides. Sand had been born and brought up in this city, and at 25 the word tide had not yet ebbed into his lexicon. He was one of the people who’d come to the organization through a scheme aimed at employing a more diverse workforce. He had a dashing smile, a kind of humble-brag stoop, it was affected, but you got the feeling it could pull the wool over somebody’s eyes somewhere, and for that, I guess I had to admire him. He wasn’t “diverse” in a racial sense—we were both white—he was “diverse” because of his class. That’s what the person who interviewed him had apparently said.

Sand was from a poorer part of town that had, according to him, a life expectancy for males of 60, lower than some places of western Africa. I’ve since looked this up and found it to be false. It’s 67 in Sand’s part of town, which is still alarmingly low by today’s standards, but not as short as in western Africa, where it appears to be at least a decade lower on average.

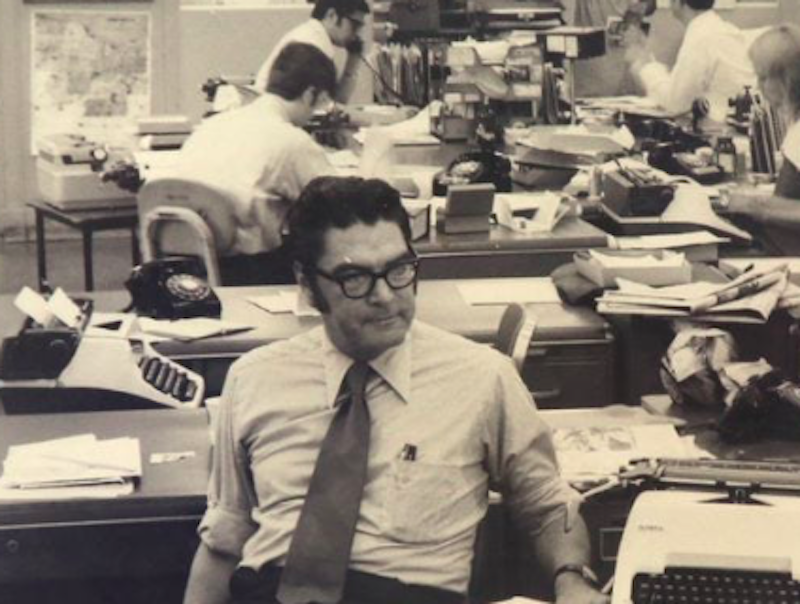

But facts won’t stop Sand. And neither will—I came to realize—spelling. I silently corrected his aberrations while thinking of the public humiliation I suffered as a trainee in my first newsroom for lesser gaffes.

I was tasked with giving Sand things to do in the churlish pursuit of putting together a radio program that brought the fractured country we both lived in some sense of the news that day.

I liked Sand as a person, but as a colleague it was tough. As worthy as the situation was—or rather is—in having him employed here, in reality, he makes life exponentially more difficult. You’ll have to work harder to get the job done. He isn’t a journalist, not yet. He’s not a reader, writer, or much of a listener. He likes football, and talks searchingly about it, as though fishing for something else. And there’re times where I recognize the stone dropping behind his askance pause, as he realizes—I don’t have a scoobie about the game.

But this isn’t about picking apart Sand. It’s about picking apart the system. Only the system could give me an extra body who was a hindrance rather than help. And no doubt Sand feels this too. Ticking a diversity employment box is one thing, but properly training someone is another, and to my knowledge Sand hasn’t been offered such support. He’s been told he’ll learn on the job, but no one has time to teach.

It goes without saying that the conversations with colleagues, not just Sand, are tepid and flat. The collective brain of the newsroom has been trepanned, of this I feel confident. And my information has been double-sourced.

There are the phrases and the buzzwords: “Let’s ask the questions no one else is asking?”, “That’ll get them talking” or my favorite, “Let’s learn on air”—which I think is at least an honest attempt at addressing the fact that we don’t know anything.

The rules of the daily game are well versed by now, but for those in need of reassurance hear me out: choose a subject that fits within the organization’s belief system, and won’t cause undue consternation to an editor, leaving them having to deal with a slew of complaints. Then, when the subject is satisfactorily anodyne, make sure the guest or commentator isn’t too lively either, and won’t stray off into areas that, again, might either offend, or offer a flash of life, or, more fundamentally disrupt the righteous orthodoxy.

Even Sand is getting wise to it. He sometimes arrives brimming with some idea that’s big and important like a mattress covered in tinsel, and I watch his face as it’s slowly put through the machine mangle, and comes out looking like a bare askew coat hanger.

What’s your life expectancy now buddy?

As you may have gathered, I work as part of a team that “makes” radio for a large media organization, under the auspices of attempting to “break” news. It’s a joke, as cheap as my salary, but the only thing that breaks is a naïve sense of worth.

But I play the game because I get paid. And paid better than my newspaper colleagues, I might add. I live in a flat, and I’m pushed towards taking narcotics occasionally on the weekends. And then once I’ve recovered from the excess, I like to read and write. VS Pritchett, Hughes, Chekov, Plath, Toibin, that’s where I’m at.

I used to work in a metropolis, but moved away because I fell in love with an artist. It could’ve happened to anyone, but I felt lucky it happened to me. Sometimes when I feel at breaking point I look at a picture she’s made, and the light shines. Being open to the possibility of miracles is all I’m left with. The reckoning and wrangling of the week ahead on quiet Sunday nights can be hard to confront, but at some level I’ve accepted it’s a price worth paying. The mountains and lochs are to the north of me, easily reachable by car and, as many say, they’re the envy of this island.

But I prefer the bike.

The truth is, I could be anywhere. I’m just clockin’ in and out, and waiting for the riverside to thrive.