The last time you heard about an "insensitive" email from college administrators sparking outrage on a campus was probably the 2015 Yale University incident that produced the viral video of "Shrieking Girl" hysterically berating Yale professor Nicholas Christakis for making her feel "unsafe," which can now mean almost anything on a college campus.

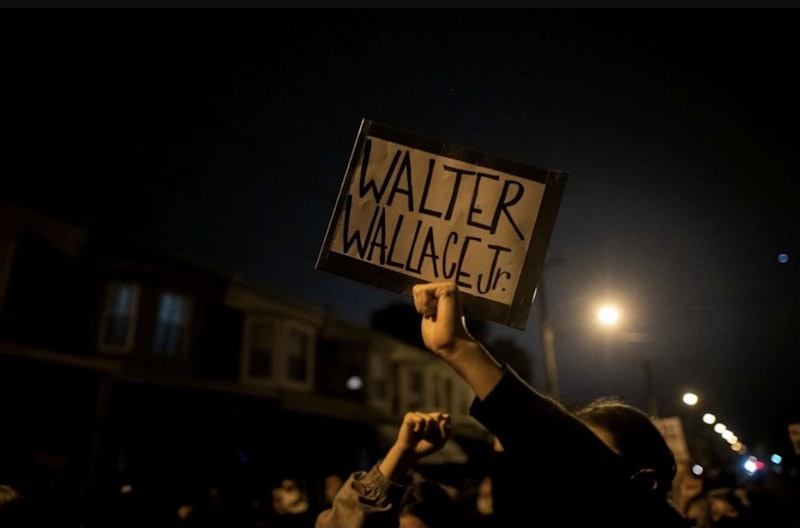

While there's been a more recent email incident, it received less media attention due to the lack of a spectacular visual "banner" to announce it. Students at Haverford College in Pennsylvania went on a strike in late-October after college President Wendy Raymond and Dean Joyce Bylander circulated an email discouraging students from joining the nearby protests against the shooting of Walter Wallace, a West Philadelphia black man with mental health issues who police officers killed by shooting at close range after he'd threatened them with a knife.

That some Haverford students wanted to join the protests is understandable, although they were mistaken to think Wallace's killing was race-related. American cops are trained to kill all knife-wielders who refuse to back down in such confrontations, a problem that needs attention. The question is whether or not the email was egregious enough to merit a two-week strike, a drastic response by any measure. In that period, students didn’t attend classes, do course work, or perform jobs at the college.

Raymond and Bylander acknowledged "the grief, exhaustion, and anger of an all-too-familiar death of a Black American killed by police officers," while warning students of the potential dangers of COVID-19 transmission and the "harm and havoc" that ill-intentioned protesters might have in mind. They were concerned about the physical safety of Haverford students, but stepped on their message by including a condescending mention of the fact that the protests "would not bring Walter Wallace back." Did these high-level administrators actually believe that students at their elite institution (18 percent admission rate) needed this simplistic reminder—one that could be construed as a justification for never having another racially-motivated street protest?

Still, each Haverford student was free to ignore the unsolicited, unwelcome advice and join the protests. As for their anger, how about a loud protest outside of Founders Hall, the centerpiece of the Haverford College campus? "Get the rage out of your system and then move on" is sensible advice, given the circumstances. But as student sensitivity to age-old campus grievances (and some new ones—e.g. microaggressions) has increased exponentially, so has the intensity of the response. Maybe waving signs around and chanting in unison outside the president's office is a "Boomer" idea that's now considered passé. Why not bring the entire campus to a halt, if you can manage it? Few on campus will have the courage to oppose you.

Watching these same struggle-session scenarios play out over and over, as if scripted, can make one suspicious. You knew, as soon as the strike—to protest "anti-blackness” and the “erasure of marginalized voices"—was announced, what the college president was going to say in response. With an appropriately solemn facial expression, Wendy Raymond thanked the aggrieved (or, alternatively, self-entitled) students for "educating" her, because the first thing you do when you're fighting for your job, or against cancellation, is to thank the very people who want to bring you down. Then she moved on to the obligatory mention of her "unearned privilege" and how it renders her incapable of understanding the plight of minorities. Raymond's eagerness to please made her sound like she was interviewing for a job, although she already had one paying $500,000 annually.

On a Zoom call, Raymond agreed to almost all of the lengthy list of jargon-filled demands that students had already presented to her (one was for Haverford to give away its land to "native nations," thus putting an end to the school), and then some. "All of the recommendations you’ve made here sound spot on and are excellent,” she said. “We can do those—and go beyond them," telegraphing what a pushover she was. Note that the president called the student demands "recommendations." Raymond did everything except wave a white flag, which students on other campuses will surely take note of. But what's her incentive to push back when almost nobody on campus would be behind her? Those students, faculty, and staff who disapprove of meekly caving in to student demands are afraid to speak out, lest they be called privileged "white supremacists."

Raymond probably doesn't believe that Haverford, founded by Quakers, is an "anti-black" institution that participates in the erasure of marginalized voices, but she has to pretend otherwise or suffer the consequences. When Evergreen State biology professor Bret Weinstein refused to play pretend in 2017, campus police told him to stay home because a mob of students was looking to hunt him down. Dean Bylander, who's black and oversees Haverford's anti-racism training, still felt the penitential need to talk about wanting to learn about how she'd failed her students. In fact, this educator who's done extensive work on promoting diversity was showing her fear of the students she'd worked so hard for, as was Raymond.

The Haverford strike brought to a halt all campus activities, including Women in STEM, Latin Dance Club, and Womxn in Economics. Professors who refused to cancel their classes found their names and contact information posted on Twitter, where Federico Perelmuter, a Haverford student, tweeted, "kill peanut.” Peanut is Raymond’s dog.

The lesson that college administrators can learn from the Haverford strike is to be extremely cautious in their email communications with students, as there are students at other colleges waiting for a pretext to flex their power by going on strike. I'd bet that if Wendy Raymond had read her email to five other Haverford administrators before hitting "send,” at least one of them would have told her why it was a bad idea.