See, it’s not an exchange, exactly, or a particular look, and there isn’t necessarily a handshake involved, or half a hug, or anything fraternal. It’s nothing that cryptic. Just a nod, usually, until you and the other party are better acquainted—then you’ll exchange names, capsule histories, words of greeting thereafter.

The point is that you can almost always count on the nod, in passing—no, wait—it’s a nod, and the meeting of eyes that doesn’t signal a look, per se, but a two-way acknowledgement, or a communication, and that communication translates as follows: “I am black, and you are black, and we both know and implicitly agree that while black may be beautiful, being black isn’t much easier than it used to be.” So it’s not a guarantee, it’s not as though the other party has your back, but I like to imagine the nod as an unconscious conferring of confidence or reinforcement of a genetically inherent sub-dermal cool.

The nod is conditional, I’ve found; the nod has limits. On the streets, the nod is up for grabs in a way it isn’t in the workplace. On the streets, the nod is returned roughly 40 percent; in the workplace, the nod is returned, on average, 90 percent of the time. In the workplace, there’s a certain understanding in the exchanged nod, a respect, game recognizing game, so to speak. The streets are the streets. In the workplace, you’re high-fiving, because hey, we made it.

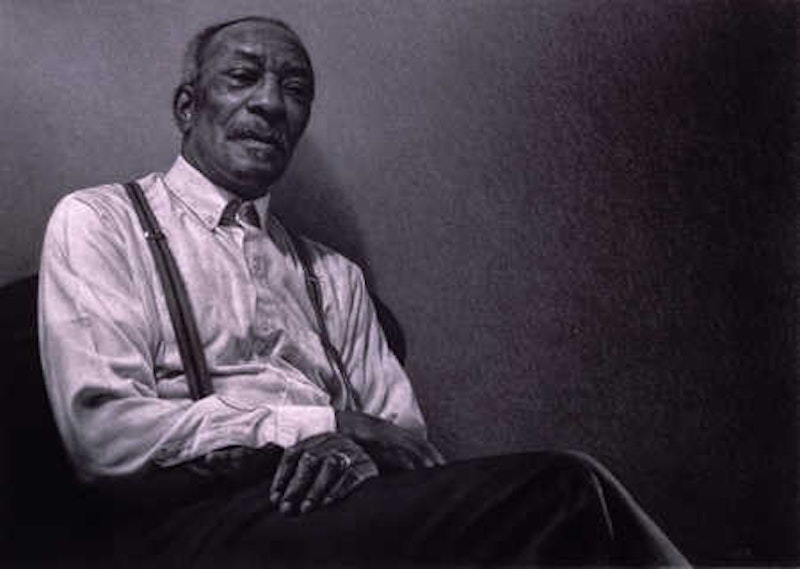

The elders treasure the nod; they celebrate the nod, they elevate the nod, they keep the nod fertile and welcoming. The elders care, because they’ve had it harder—they know your struggle and hustle, even if you yourself don’t, quite. In you, they see the selves they used to be; in them, you see the gregarious deacons and pastors, the worried aunts, the proud uncles, the kindly grandmothers, yourself, someday.

The youth? The youth could take or leave the nod. To the youth, equality’s an inalienable right, and you’re just another familiar stranger. You can always tell the ones for whom tradition is of no value: their eyes dodge yours, aimed forward and locked upon prizes larger and more personal than any lingering concept of racial or ethnic solidarity. Maybe there’s a fear there that the nod commits them to something or connects them to a history they’re unable or unwilling to fully confront, or maybe they’re over it in a way that doesn’t quite make sense to someone of my generation.

And yet that’s the endgame, right? And it’s a double-edged sword: in a post-racial world, the nod will be completely and utterly irrelevant, a signal that there’s no longer any class or value significance to the color of one’s skin, but in gaining that leveled playing field, we’ll lose something of that easy familiarity, that semi-anonymous unity. It probably won’t happen during my lifetime, but it’s weird and sad to know that it’s as inevitable and unstoppable as peak oil.