In the 1980s, there was a movement in super-hero comics toward the grim and the gritty. Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Night Returns are singled out as major works that brought super-heroes down to street level, made violence more brutal, and fighting crime more of a straight fight. But Miller had been doing the same thing with his Daredevil run for Marvel, starting as a writer in 1981. The first Punisher mini-series appeared in late-‘85. Wolverine’s first mini-series was in 1982. Something was in the air, in the early- and mid-80s.

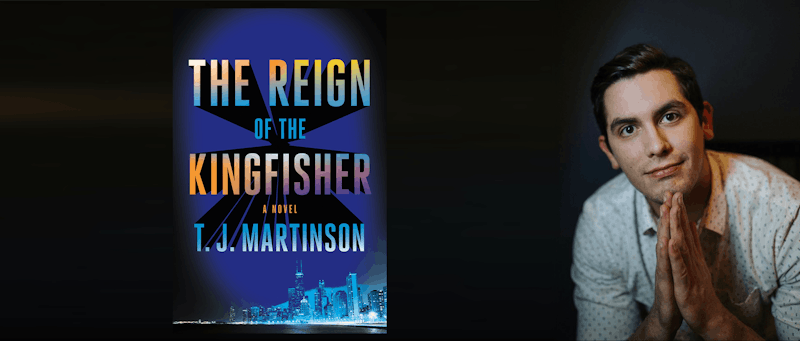

T.J. Martinson’s recent novel, Reign of the Kingfisher, imagines a brutal super-powered vigilante who roamed Chicago back in the early-80s, apparently dying a somewhat mysterious death in 1983. But now, in 2019, someone expresses doubts about that death—by taking hostages who have some connection to the Kingfisher, and executing them on YouTube. A varied group of characters start trying to figure out what’s happening, and what exactly happened back in the early-80s.

The tone’s much more like the darker comics of the 80s than the bright pop confections of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Martinson marries super-heroes with crime fiction, and for a while the result’s quite readable. The prose is smooth—it’s not lurid the way Frank Miller’s crime-oriented hero comics were, and not particularly “literary” despite what some reviews claim, but is certainly well-polished genre writing. The multiple plot strands work, at least for the present-day characters, and are juggled with dexterity.

Maybe the most effective aspect, though, is what Martinson doesn’t do. Super-heroes are fundamentally visual characters. They wear bright primary-coloured costumes, they swoop acrobatically through the air, they lift huge blocks of machinery in a collapsing underwater base. How to convey that in prose?

Martinson’s clever judo move is to not try. His Kingfisher spends the modern-day scenes missing in action. Even in scenes flashing back to the past, we don’t often see him. More often we see the results of his actions, described with crime fiction’s studied no-bullshit approach to the effects of violence. Again, it’s an effective echo of the bleak hero comics of the school of Miller.

There are significant problems, though. The flashbacks slow down the story at bad times. The kind of plot Martinson’s created, and the way the plot works out, needs propulsive motion to work. The villain sets deadlines before he kills, so you need a sense of the clock ticking down. When the book flashes back to the past, that sense is blunted.

The flashbacks provide story beats that move things along, but don’t have a story to tell in and of themselves. There’s something that eventually passes for a dark secret, but it isn’t really foreshadowed, and when we do learn it, it’s told in retrospect rather than depicted in a full flashback. (And told at the climax, where events are slowed down by the exposition.) A comic book would know better; would make sure to foreshadow the mysterious revelation that will change everything you know.

There are some nice character moments in the book, like a grizzled journalist talking about his wife’s death by a brain aneurism. But there are also moments that challenge credibility. A member of an underground hacker collective leaving a compromising voice-mail, for example. The villain’s motivation is flawed: there’s no reason he launched his evil plan in 2019 as opposed to years before. And a violent man is left psychologically shattered by killing the wrong people—not regretful, but broken. His relationship to violence needed to be explained more for this to be believable.

The book’s idea of heroism falls at the final hurdle. Martinson is fairly clear that while it’s understandable why the Kingfisher’s treated as a hero, it’s ultimately a mistake to do so. And he does celebrate activists, whether the everyday sort or the fictional hacker collective he creates called the “Liber-teens.” But he accepts the Chicago police (the same guys who had an off-the-books interrogation center) as a force for good, even if some of his characters don’t. And he strongly implies that one of the more idealistic characters of the book should work with a high-ranking police officer. That uneasily calls into the question the line between activism and vigilantism.

(As an aside, the Liber-teens wear masks of Robespierre, a cute play on the Guy Fawkes masks of Anonymous popularized by Moore’s V For Vendetta. The problem is that the Fawkes mask had a cultural background long before Moore got to it, in a way that Robespierre doesn’t. And Robespierre, known as “the Incorruptible,” doesn’t fit with a group whose name is a play on “libertines.” It’s clever, but like much in the book, falls apart if you look too closely.)

There are a number of good things in Reign of the Kingfisher, but it feels as though each has a countervailing problem. Martinson keeps the power levels low and so the Kingfisher is believable. But then wouldn’t someone even a little superhuman have made nationwide news in the 1980s? Martinson chooses not to reveal much about the Kingfisher’s past or origin, keeping him something like a natural force; that’s not a bad approach, but in this context the Kingfisher’s left too undefined, without a human past.

The action, when it comes, isn’t especially effective, and the climax doesn’t work. The staging of a fight scene’s poor (one character doesn’t go for another character’s gun when she probably should); and there’s a lack of tension, with a SWAT team just offstage. The villain’s more pathetic than impressive.

But the book’s not bad. It’s a super-hero story without a super-hero and almost without fight scenes; a crime story without an underworld; a mystery without suspects or at least without clues. And it almost works. The prose moves nicely, and gives the characters individual thoughts and thought patterns. It doesn’t rise to handle gravitas in any original way, but it gets across what it needs to. It entertains, at least to a point. There are a lot of super-hero stories that can’t say as much.