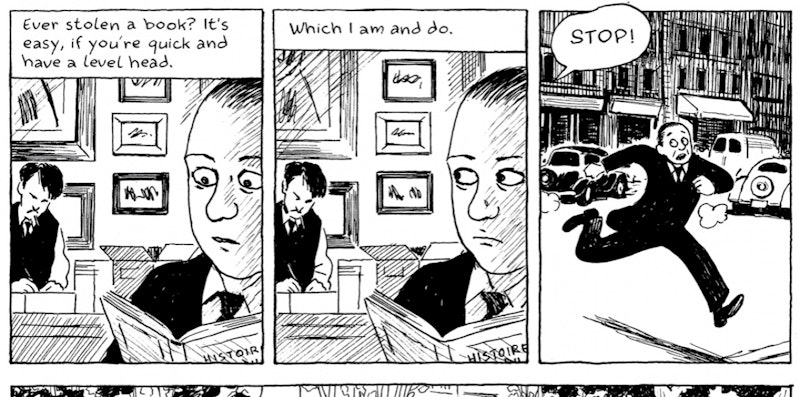

Translating a graphic novel might sound simple; there aren’t that many words per page. In fact, there are significant difficulties. First, because there are so few words, good comics writing has to be like good poetry: tight, not a single syllable wasted. Second, because it’s important to keep the art clear, the space that can be given to word balloons and captions is limited. Put this together, and you have a problem for unwary translators. Dialogue has to match in tone and register while fitting into almost the exact same amount of space. Wordplays and double meanings have to be respected without expanding the text.

Edward Gauvin’s translation of Alessandro Tota’s writing in The Book Thief is possibly the best translation of a graphic story I’ve read since Anthea’s Bell’s exquisite work with the puns in the Astérix books. Gauvin’s task was much different, having to find dialogue and first-person interior monologue that feels real and idiomatic yet thoughtful, instead of finding analogues for knockabout wordplay. But he pulls it off about as well, and thanks to him the work by Tota and Pierre Van Hove feels like a living English text.

The book’s worth the effort, a pleasant yet downbeat tale about Parisian literary life in the 1950s. We follow the career of Daniel Brodin, an aspiring poet who makes his entrance into literary society by reciting a poem before a gathering of highbrow writers in a smoke-filled café. Unfortunately the poem isn’t his own, but an obscure Italian work for which he improvised a translation. One of the attendees lets Brodin know he’s on to him—but before long Brodin’s fallen in with another and far less reputable group of artists, who plan to announce the plagiarism in a public manifesto by way of embarrassing the first clique.

Brodin’s not sure he wants this, just as he’s not sure whether he wants a relationship with upper-class student Nicole or rural beauty Colette. He’s not sure what pose to adopt. Or what to do as goon Jean-Michel begins to carve out a name for himself as a bad-boy poet—while Brodin has his inspiration dry up. Until Jean-Michel starts talking about a last big score he has in mind, which Brodin incorporates into a feverish autobiographical novel.

You can see disaster brewing, but in truth you can see it coming from almost the start of the book. Brodin’s lacking in conscience without being unsympathetic, and the graphic novel works as a kind of picaresque story that takes place almost entirely within Paris. It becomes an effective meditation on the boundary between art and life, and especially between art and crime.

The visual storytelling is very strong, fluid enough to be amusing and yet classical enough to conjure up the sense of an older time. Panels are laid out in tiers, with clear gutters between them. The approach, along with the black-and-white art, recalls a Hugo Pratt as much as a Marjane Satrapi; even perhaps Hergé’s clear line. It’s also a little like a cleaner Eddie Campbell, in the way its cartooniness gets across the life and personality of characters while also conveying a sense of architectural precision. Nicely capable of opening up from precise yet cartoony rendering of reality into hallucinatory patterns of altered consciousness, this is precisely the right approach for the story.

This unfolds through an unobtrusively intricate set of flashbacks and plot strands. Thievery leads to thievery as Brodin, aiming at a life of art, sinks further into dishonesty and crime. For Brodin, art is amoral, and indeed this is a setting in which a goon like Jean-Michel can be hailed as an artist. Brodin’s failure, perhaps, is to be unable to rise above his time.

The book deftly evokes the actual Paris literary scene of the 1950s. There are cameos by relatively minor figures like Roger Nimier and Raphaël Tardon as well as, inevitably, Jean-Paul Sartre. A passing resemblance between Jean-Michel and Jean Genet is acknowledged when Jean-Michel (in his telling, at least) beats the hell out of Genet. But perhaps most interesting is the similarity between Brodin, who as the book opens is a law student raised by his grandparents, and Situationist writer Guy Debord, also a law student partially raised by his grandparents.

Debord was part of an anti-art movement; similar to the one Brodin becomes involved with. A semi-hallucinatory hours-long wander through Paris taken by Brodin and friends is directly analogous to Debord’s idea of the :dérive” or “drift,” an aimless walk through an urban space with the aim of creating situations—moments, happenings, things not encoded in art but lived directly. Given the graphic novel’s title Memoirs of a Book Thief, it’s interesting that Debord’s first book was his Mémoires, deliberately published with sandpaper covers so that it would damage books next to it on a shelf.

For better or worse, though, Brodin isn’t Debord. He’s not opposed to art. He dreams of being a great poet. The joke is that there’s no real sign that he can manage it. On the other hand, Debord’s dream of living through situations with the power and vividness of art does describe the life Brodin ends up with. And Debord’s scratching “Never work” into a wall by the Seine is matched by the contempt for work Brodin and his friends articulate.

A first-person story told by an admitted plagiarist raises questions of how reliable the narrator is. Part of the accomplishment of Memoirs of a Book Thief is that we don’t wonder that about Brodin. He’s not that subtle. He’s a man who always looks ahead to what he believes to be inevitable triumph, without accepting the reality of his failures. As a result, he never ends up where he wants.

The book ends with neither disaster nor triumph, having made its point that while Brodin’s slippery enough to indefinitely avoid the former he’ll never reach the latter. He has no real ideas, and we know, decades on, that no Daniel Brodin made a great career as an artist. And yet, in his lack of self-consciousness, in the situations he manufactures for himself, he nevertheless makes himself into a fine character to read about.