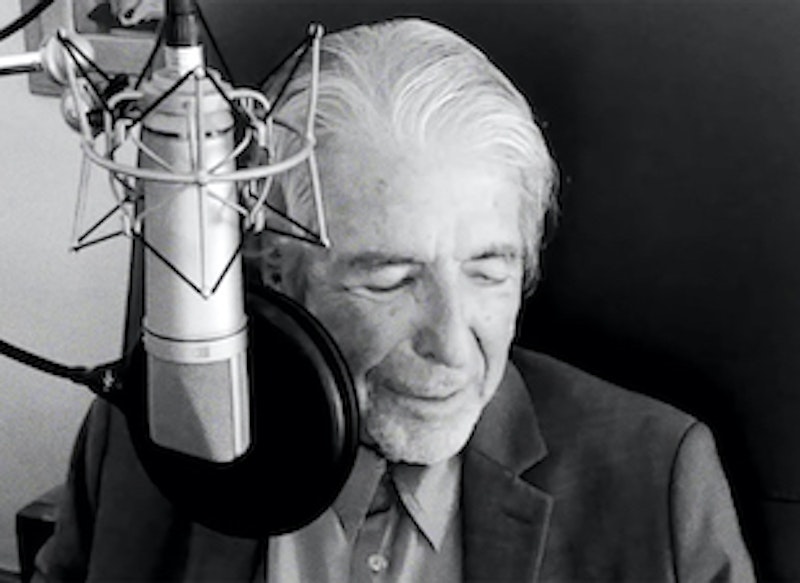

Leonard Cohen, who died at 82, was just beginning to find his voice as a singer/songwriter. What remains are tantalizing glimpses of a talent that might’ve emerged, given time, as something unparalleled in the annals of pop music.

Many people have complained that the arrangements on Cohen’s later albums were frequently a little bit on the cheesy side. There are synthesizers that sound so cheap your kid’s Yamaha could do better. There are terrible female backup singers, sabotaging the second half of every line. The fact that a song like “Everybody Knows” is good at all, given these impediments, just grows more amazing over time.

Well, your complaints have been heard—not by Leonard Cohen, who couldn’t give a fuck, but by his son, who’s hired really good studio musicians to play a bunch of little flamenco-tinged acoustic solos. It’s tasteful. It’s elegant. (Well, sort of. This kind of paint-by-numbers music is about as elegant as serving tiny crème brûlées in little ramekins, putting candles in empty wine bottles, or accessorizing with a scarf in the middle of July.) After three songs I was so desperate for a cheesy Yamaha riff, or a pathetically earnest backup singer, that I almost started playing Erasure records. Anything to escape from yet another interlude brought to you by Acoustic Guitar Hero.

Remember what happened when the non-assassinated Beatles got back together and recorded “Free As A Bird”? For about 10 seconds, everyone thought we’d been granted a miracle: a brand-new Beatles record. But then, around the edges, a merciless reality began setting in. John Lennon sounded eerily dead, since his voice had been airbrushed almost beyond recognition. The Paul McCartney bridge was a shameless rip-off of “Remember (Walkin’ In The Sand),” brought to you by “A Day In The Life.” Slowly, inevitably, “Free As A Bird” became what it was: a sad little antiseptic failure, buried along with its name.

This new “Leonard Cohen album” is a bird of a similar feather. It’s coasting on some understandable nostalgia, and it’ll be a while before anyone feels brave enough to ask which tracks are supposed to be the good ones. But sooner or later, when 2019’s holiday CD gifting rush is over, many among us will quietly point out that the cadaver isn’t wearing any clothes. Right now, that’s as taboo as asking whether Daniel Lanois—one of several people on this album who get a lot of love in its media kit—has ever been actually good without Brian Eno.

You can’t step in the same river twice. You Want It Darker, a fine but uneven album, was already the singer’s farewell album. We’ve already heard Cohen screw up his phrasing (e.g. on “Treaty”), and said to ourselves, “Oh yes, I understand, that makes it sound more real.” Now they’ve made a new song with the same exact messed-up phrasing. (I give you “What Happens To The Heart,” this album’s opening gambit.) Instead of sounding authentic, Cohen’s lazy “raw takes” are probably now going to be remembered too clearly, as one of his many unfortunate tics.

It’s also impossible to add meaning to every song on this re-do simply by stirring in a little mortality. There was a clever balance, on You Want It Darker, between songs about dying (the title track) and songs that had nothing to do with dying (“It Seemed The Better Way”). They were both thrilling: “Oh look, this song confronts his impending death! And on this next track, he humbly sidesteps the issue altogether!” That was no accident. Cohen knew how to paint with such externalities. It’s a trick the new album hasn’t learned, so every song comes off like a speech, at a wake, about how Leonard would’ve wanted us to enjoy ourselves. Let me ask you: How much of that can you really stand before you switch recordings?

There’s no mystery to be plumbed anywhere on this album. I listen to Cohen’s song “Avalanche” probably twice a day, every day, and I still don’t fully understand it. When Cohen sang—speaking of “You Want It Darker”—that “you want it darker/We kill the flame,” there were a thousand things he could’ve meant. This album’s typical cop-out, on the other hand, is a line like this: “I took her to the river/as any man would do,” which is about as literal as, say, the poetry of Blink-182. There was a nearby river. He took her there. Boy, was she a knockout, back in those days. And then they had sex!

The artist is engaged in a perpetual war against himself. He’s sentimental, for instance, and overly kind to the memory of people he treated badly. So the songs come from his stubborn, perfectionist attempt to be more than a nostalgic hypocrite. Or he’s prone to idiotic fits of mystical joy and simple-minded religion. So the songs come from whatever’s left of the sermon after you cut out all the preaching. That’s what happens ideally, I mean. On this album, unfortunately, the first draft was all they had to go on. We’ll never know what Cohen would have replaced “listen to the... butterfly” with. The hiccup says it all: Cohen knew a placeholder when he sang one. He was waiting to do better with that line when death carried him off.

Therefore, for all of the above reasons, I award Adam Cohen’s unfortunate, unpalatable act of mourning no points. Thank God his father’s catalog of brilliant, raspy essays, mostly about ex-lovers and Judgment Day, was already complete.