One of the ways for singers to make a bid for country immortality is to create themselves as characters or legends—a Hank Williams, a Patsy Cline. Hank still provides the template for traditionalist-minded male artists such as Cody Jinks; it's impossible to think of the character Jinks inhabits on his recent albums except in relation to the line-up of self-destructive hyper-emotional geniuses like Johnny Cash, George Jones, even Chris Stapleton. On the other side of the great gender divide—though Tammy, Loretta, and Reba provide templates—the materials out of which female artists like Miranda Lambert are assembling the characters they inhabit are by and large of more recent vintage. Really, Miranda's invented a lot of them herself.

Every month many people try to stage themselves as country legends, and fail. The music is what makes it stick, if it does, and Cody and Miranda definitely have that part. Jinks and Lambert are both Texans, which is a good start, and make a good match on a playlist. Their bliss may be doomed, however, due to their extremely dark sides. Are they partying happily or devoured by the darkness within? Always hard to tell one from the other.

Country is musical tradition, but it's centrally also a theatrical tradition, with the characters presented on stage complexly related to the humans singing the song. As in hip-hop, for example, it's hard to separate the memoir from the novel, the art from the artist, the story from the truth. Both singers portray themselves as victims of themselves, helpless to resist when their dark and/or party side emerges. They're sorry if they hurt you, but they're not really in control. Miranda takes this in fairly good humor; Jinks uses it as an occasion for self-examination and self-laceration. Or at least, the character that narrates his songs does that.

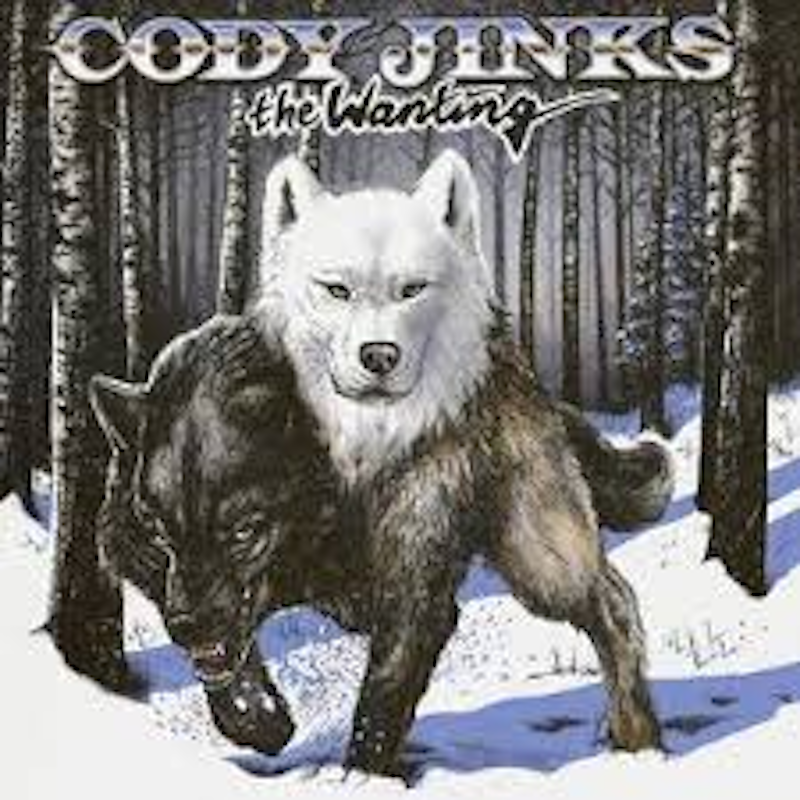

A couple of weeks ago, Jinks, a recovering heavy metal singer who’s as good as anyone working in a traditional country vein right now, released two albums, more or less simultaneously. Perhaps these are meant as a kind of yin-yang: After the Fire the light side, The Wanting the dark. That seems to be the governing metaphor of the project, as summarized on the latter album's art, featuring a black and a white wolf in some sort of profound or goofy merger.

I've been the song carried in on the breeze.

I've wept with willows and I've fell with leaves.

Well, I am the badlands and the silence it holds.

A warrior who walks but is never alone.

There's a black and a white wolf in me.

And I live and I die by which one I feed.

It's a war old as time, this fighting inside.

And I live and I die by which one I feed.

You'd have to say that's dramatic. Perhaps overly so, and the Jungian symbolism of masculinity threatens to tip over into self-parody: "It's the people who love me who suffer the most," he says, in a line that could summarize Waylon's later output, and a lot of other people's too. One is not entirely surprised when he sings, "I'm just a guy with a wounded mind." It's as though the wild hijinks (pun) and legendary self-destruction of a Waylon Jennings or David Allan Coe has been transferred by Jinks to "the inner terrain," rendered over into a pure psychodrama. But as I listened and began muttering at my speaker that Cody ought to lighten up, he beat me to it: "Maybe the light at the end of the tunnel ain't a train," he admits. That would be a dangerously positive outcome for this sort of country singer, but then again there is that “Maybe.”

If anyone can be convincing on something like this, it's Jinks and his band and production team. Country hasn't sounded any better since early Alan Jackson, or Pete Anderson's recordings with Dwight Yoakam. "Think Like You Think,” for example, is given a perfect arrangement, as traditional as could be imagined, and there are references everywhere to classic country, particularly the neo-traditionalist phase (say, 1989-95): John Anderson ("The Wanting" echoes "Seminole Wind") or Ricky Van Shelton, but also John Prine, to whom everyone is paying homage these days. The fiddle kills. The drums swing beautifully and are mixed with great presence. There's even a Bob Willsy instrumental workout ("Tone Deaf Boogie"). The basic Waylon thump of "The Raven and the Dove" (again with the light and dark sides of Jinks) sounds newly alive. Jinks delivers the material with the sort of authority that lends it credibility; he rolls along pretty deep.

Miranda's Wildcard picks up her persona where she left off before she paused time itself for her masterpiece double set The Weight of These Wings (2016). Here she's back to the rowdy girl who means to do well but doesn't always, or always doesn't. Meanwhile all the material performed by the Queen of Country Music takes place against her rocky, very interesting love life. "I've got a track record; my past is checkered," she tells us, perhaps unnecessarily. "Girls like me don't mean it but we don't know better." She's not with Blake Shelton, of course, or Anderson East, but has married a policeman from Staten Island and moved to NYC. There are occasional signs of this, not only in the lyrics but also in a couple of flirtations with Taylor Swifty pop (on "Mess With My Head," which I'm not quite feeling, and "Settling Down," which I am).

She has more than earned the right to embody an archetype, and it's the music rather than the actual love life that constructs Miranda as a character and a legend, in a long series of four-minute vignettes through which she drinks, loves, swaggers, loses, and swears sweet revenge, her specialty. "It'll all come out in the wash," she promises. "You take the sin and the men and you throw them all in, and you put that sucker on spin." These days, though, she's winking at her former threats of violence against assholes she has dated, as on "Way Too Pretty for Prison," a tribute to or swipe from Brandy Clark's Stripes. But perhaps she was always winking.

Whatever the reality of Miranda Lambert's life may be, she portrays herself, in her own words, as a white trash bitch. Wait, don't blame me for my vulgar diction, blame such lyrical constructions as "I just can't keep my white trash off the lawn" and her new candidate for Miranda national anthem, "Pretty Bitchin'." On the other hand, it's often the gentler, more rueful or meditative songs that sneak up on you and remind you that Lambert can really sing. She, too, proves that classic traditional country is still possible, on "(He Can't Love Me Like) Tequila Does." It's hard, as often with a country star you like, not to worry a little about the alcohol. On the other hand, correlating "Miranda Lambert" with Miranda Lambert is never a straightforward matter.

On this album, she's almost willfully true to the larger-than-life character she inhabited in her classic series of albums from the early 2010s. "I'm like a locomotive; I don't run out of steam. New York seems okay. I'm a little more Tennessee, and I've got whiskey in my veins." But like Jinks with his light at the end of the tunnel, Lambert goes for small redemptions, as on "Bluebird." I'm wondering, as she seems to be, how well NYC is going to work for her in the long run. She co-wrote all the tracks here, keeping autobiography in play, but she wrote with everyone: Luke Dick, Natalie Hemby and Lori McKenna (recently spotted among the Highwomen), Ashley Monroe, Brent Cobb, Jack Ingram, etc. And she's a model for emerging female country singers; maybe she'll be their Hank.

If I were pondering what the future holds for Cody and Miranda, I’d speculate that in their cases—as perhaps in our own—we’ll witness a serial depersonification, or a removal of masks. Or perhaps just a mutation; eventually, if Jinks survives all those dark corners of his own mind and Miranda all those "dark bars" where she still apparently hangs out, they'll be meditating ruefully on their misspent youth, or at least the misspent youth of the characters they've created.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell