Among the body blows that the popular American cinema has been under since the start of the coronavirus pandemic: it soon may be illegal to release a “misleading” trailer for a film. Producers of the 2019 Danny Boyle film Yesterday lost a lay-up lawsuit and two assholes made out like bandits: Ana de Armas appears in the film’s trailer, but not in the movie itself. “The two de Armas fans, Conor Woulfe and Peter Michael Rosza, each paid $3.99 to rent Yesterday, an alternate-history speculative film about the disappearance of The Beatles, on Amazon Prime. de Armas’ part was cut after filmgoers responded that they didn’t enjoy the fact that the main character’s love interest (played by Lily James) had competition in the form of de Armas’ character. Woulfe and Rosza are seeking “at least $5 million as representatives of a class of movie customers,” according to Variety."

Every moviegoer learns early that what you get isn’t always what you were promised. Movie trailers are some of the most consistent reminders of this. From Robert Zemeckis’ Casataway spoiling itself and inadvertently telling the entire story of the movie in three minutes; to the debacle of 2007’s deceptively dark Bridge to Terabithia; all the way back to movies “starring” Brooke Shields, like Alice, Sweet Alice, which came out after 1978’s Pretty Baby and has her in it for about two seconds. None of this has changed, which is only a testament to how hard it is to sum up the feeling of a feature in so little time. Beyond indicating a broad genre and who’s in it (and maybe who made it), movie trailers don’t have much else to sell. They have plenty to say, though—many people prefer trailers to the films they promote (Licorice Pizza is a recent example I heard often, probably because it has so much footage that isn’t included in the final film).

Bicentennial Man was released at the end of 1999, a family sci-fi drama/comedy that spans 200 years starring Robin Williams as “Andrew,” an Isaac Asimov style home robot. The film is based on an Asimov story, “The Positronic Man,” but the movie is hardly Foundation or I, Robot. This was the trailer for Bicentennial Man. Watching it now, it’s even more misleading, emphasizing the film’s first 20 minutes and only indicating through montage what happens for the rest of the movie. You do see Oliver Platt’s benevolent robot doctor explaining something to a now-android Andrew, and there’s a sense of some kind of ascension, salvation, or release for Andrew. But most people would assume this is a lightweight Robin Williams comedy, perhaps a bit bitter like divorce-driven Mrs. Doubtfire, but a robot’s desire to become an android and then a full human hardly sounds sad—it looks easy-breezy in that trailer.

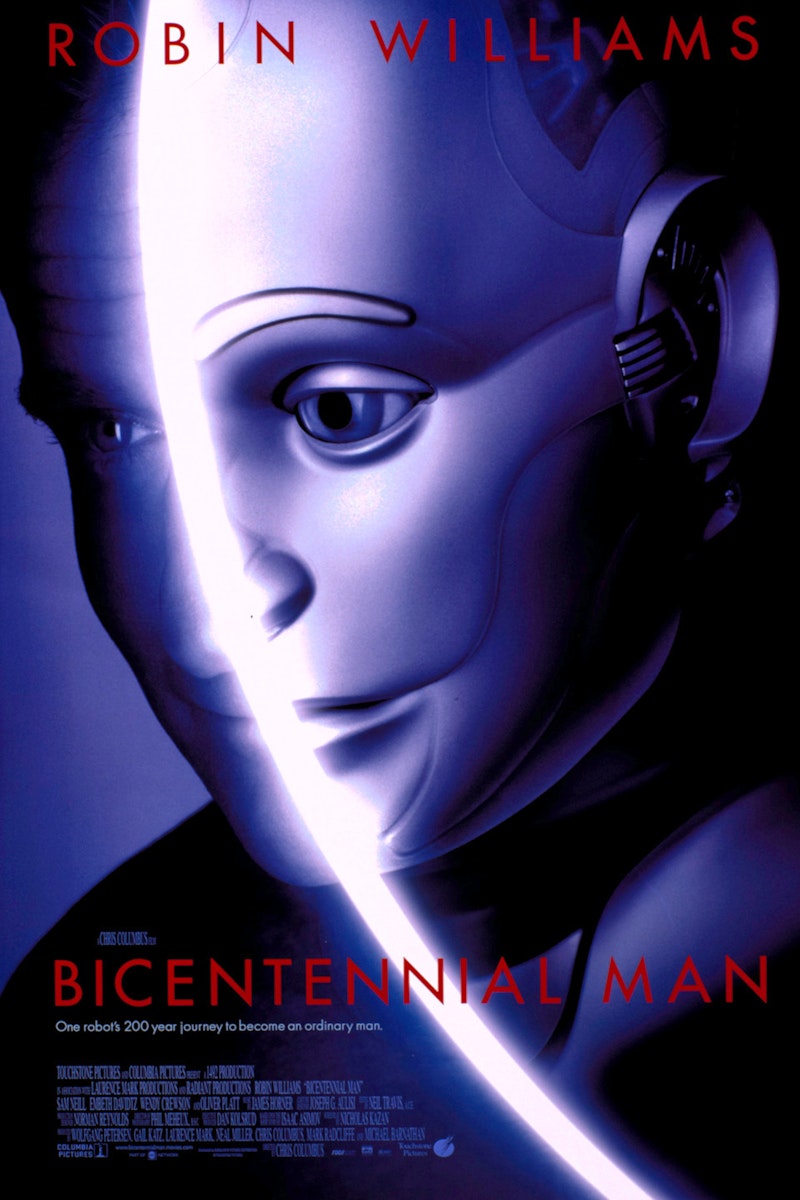

I saw Bicentennial Man at the end of 1999 at the United Artists Union Square 14. It came out on December 17, and I know that we didn’t see it on or after Christmas; it was probably Sunday the 19th. It was just my mom and me, and I’m sure what caught me wasn’t the trailer but the poster, a remarkable work of pop ephemera that I hate to admit is stronger than the film itself. In my memory, Bicentennial Man was more of like an epic tragedy, and only when the final shot faded out did I realize I conflated this and parts of Steven Spielberg’s equally dizzying A.I.: Artificial Intelligence from 2001. Bicentennial Man does run slightly over two hours, but Andrew doesn’t encounter as much resistance, heartbreak, or mockery in his 200 years as I remembered.

Directed by Chris Columbus—who made this right before the first two Harry Potter movies—Bicentennial Man tells the story of Andrew, an NDR home robot purchased by the Martin family, led by father Sam Neill, mother Wendy Crewson, and daughters Angela Landis and Embeth Davidtz. When we meet them in the spring of 2005, the daughters are still really young, and for the first 25 minutes, they’re played by Hallie Eisenberg and Lindze Letherman. These are the kids you see in the trailer. You see Davidtz, but you don’t know that she’s grown up Eisenberg, or that she plays both the adult daughter and that character’s granddaughter. One of the more interesting scenes in Bicentennial Man features Andrew returning from a decade-long odyssey to find other robots like him, “anomalies” with personalities. He eventually finds Oliver Platt and his safe haven of futuristic Frankensteins.

Eventually, of course, Andrew’s given a human face—so we can see Robin Williams himself (he doesn’t appear “out of robot” until more than an hour into the movie). Andrew comes back to the Martin house years after he was freed by Neill’s now-late patriarch. He walks into the house and sees Embeth Davidtz playing the piano, except she’s decades younger. Even more startled is Davidtz, who shrieks and calls for her grandmother, also played by Davidtz. Understandably confused, Andrew asks how two people can look “the same,” and the grandmother responds, “Genetic resemblance. It skips a generation.” Of course, it’s more than a resemblance, it’s the same person, and while some may think I’m stressing an obvious and meaningless point, movies, whether they know it or not, are constantly dealing with the question of what’s real and what constitutes reality. What would’ve been a formulaic mistaken identity screwball scene turns into something much stranger and disturbing.

Neill dies halfway through the movie, and besides the daughters played by Davidtz, the rest of the family drifts away (we never see the mom die, nor the meaner older sister). Davidtz is both “Little Miss,” who we meet as a young girl at the beginning, and Portia, Andrew’s love interest for the last 45 minutes of the movie. After some mild resistance, Portia calls off her wedding and begins living with Andrew, despite the Supreme Court’s rejection of their request for marriage and personhood for Andrew. The disqualifying factor is his immortality, so Andrew decides to “die with dignity,” as testifies as much 30 or 40 years after he’s had Oliver Platt install blood into his system, the final ingredient which will degrade him over time and eventually cause his death. Bicentennial Man ends with elderly Andrew and Portia in beige space beds watching that same Court many years later granting him personhood and them marriage. Andrew dies mid-speech, and Portia asks to be unplugged. The final shot is a close-up of their hands that fades to black. Celine Dion sings over the closing credits.

Bicentennial Man is an extraordinary film to show to children. I was seven when I saw it, and vividly remember walking past Forbidden Planet and The Strand looking at the pavement, beside my mom, feeling completely drained. The movie blanked me out, with a dizzying and unusual structure that resembles a much better film that I saw nine years later, Synecdoche, New York. At a certain point, half an hour to 45 minutes in, time starts accelerating, and by 90 minutes, you’re in a completely different world than you began. These movies move through tone and time: although both start out with more humor in the foreground and end with big strings and tears, the rollercoaster timespan of Bicentennial Man and Synecdoche, New York isn’t used often because it’s upsetting and off-putting, especially when it’s unexpected. Adam Sandler’s Click from 2006 is another metaphysical genre curio that had extremely misleading trailers, and to quote my friend Leigh Ann, “It made me mad because I didn’t think Adam Sandler movies were allowed to be sad.”

More than sad, Bicentennial Man is a mind-blowing PG-rated family movie funded (mostly) by Disney, one that bombed upon release, one that Williams admitted he “regretted making,” a movie made all the more melancholy and tragic because of its tonal inconsistencies, bland bright TV lighting, and schmaltzy score. Synecdoche stands up far better today, but now I consider it a teenage masterpiece, maybe one that I’ll love more in a decade or two—it’s that powerful. Bicentennial Man isn’t, but I’m still struck by how directly and perversely it deals with death, and considering my reaction, how it must’ve been one of the first time I really thought about what how multi-faceted death was: Andrew could live forever, but he loves Portia, and “cannot stand to live in a world without” her. People in my life had already died, and my uncle Doug was dying. It drained me and made me feel as blank as this movie. Why would someone choose to die? While enormously sad, I understood then why he had to go: he loved someone.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith