The Cineplex Odeon Chelsea opened on 23rd St. just two doors down from the Chelsea Hotel in the summer of 1989. Nine of its 11 screenings played Do the Right Thing, then in the middle of its domestic first run. By the time I started going there as an infant and toddler in the mid-1990s, it was still a Cineplex Odeon theater; by 1998, Clearview Cinemas took it over and ran it for a decade before handing it over to AMC and eventually Cinépolis—the theater still stands, is still open, and looks completely different. Like most of the Manhattan multiplexes I went to as a kid, the big movie theater next to the Chelsea Hotel is now “luxury oriented,” with fewer, “more comfortable” seats. I hate these kinds of places, where you can buy tickets to sit on a disgusting pleather sofa that smells like the inside of Chuck-E-Cheese’s asshole. The worst you can say about regular theaters—whether they’re chain multiplexes or independent single screens—is that they smell like popcorn, Coca-Cola, coffee, and poison butter. Like libraries, movie theaters have a common, distinct smell, an ether in the air of all of the above. Like the specifics of a kindergarten cafeteria, it’s the kind of thing carved into your nervous system.

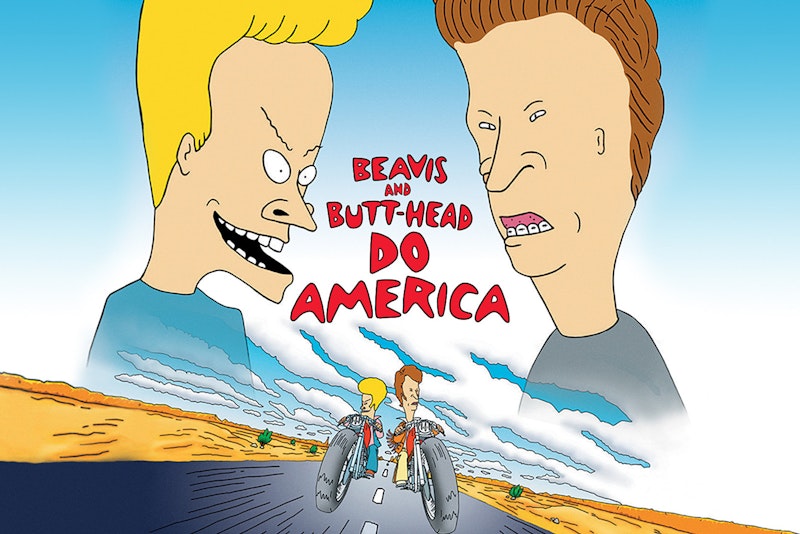

Maybe that’s why I couldn’t remember where I saw Beavis and Butt-Head Do America during the last week of 1996. Pocahontas was the first movie I saw, but I remember nothing, not even where; but one of my earliest memories is sitting in the theater pictured above during the peyote scene in the desert. I don’t remember anything else from that day, but I can see myself next to my dad and Michael Gentile watching Beavis tripping in the desert to a Rob Zombie song. This is the earliest memory I can place that I know I didn’t make up or conflate with something else: it wasn’t upsetting, and by no means terrifying, but it left me wide-eyed and pinned to my seat. My dad remembers that day, and could place it at the Cineplex Odeon, where he said most of the crowd were young, gay artists who assumed he and Michael were taking their hip son to the cool new groovy movie from Mike Judge and MTV.

I’ve seen it since, but watching Beavis and Butt-Head Do America this week only solidified my opinion: this is a perfect movie. Like Heathers, Zoolander, and Legally Blonde, there isn’t a wasted frame or joke. It’s not that every joke lands—every joke kills. At 81 minutes, it’s as tight as a movie can be and a model for pacing and editing in all film, not just animation. The movie opens with a giant Butt-Head destroying a city like Godzilla—Beavis wakes him up from this dream and, after connecting and reconnecting and reconnecting and connecting and reconnecting the dots (broken glass, busted front door, messy house, missing TV), Butt-Head realizes that someone stole their TV. When I saw Beavis and Butt-Head Do America in 1996, at four, I know I’d never seen their show on MTV—but I knew a TV was something you’d look all over America for.

And I know that when I say I saw Beavis and Butt-Head Do America in a theater when I was four, it might sound like I’m bragging. Well, you’re right, I’m fucking bragging!

What struck me the last time I watched it, maybe a decade ago, and now, was how little it had dated and how close it had remained to my sensibilities. Like Zoolander, which is as funny and fresh as it was when I saw it on September 28, 2001, the plot of Beavis and Butt-Head Do America could be remade today beat for beat, with few superficial adjustments. After fumbling their way upwards as ersatz hitmen for a biker (Bruce Willis) looking to get rid of his super criminal wife (Demi Moore), Beavis and Butt-Head end up on a series of planes, trains, and buses, often accompanied by an elderly lady voiced by Cloris Leachman (the second time they see her, Beavis tells Butt-Head, “Hey Butt-Head! There’s that slut from Las Vegas.”) Robert Stack plays an FBI agent obsessed with cavity searching every witness possible, and after a confused rendezvous with the wife, she plants the movie’s MacGuffin in Beavis’ pants and splits. Stack’s agent repeatedly asks Beavis, Butt-Head, and various other individuals to “give us the unit.”

Of course they fumble into a happy ending and congratulations from President Bill Clinton, who makes them honorary members of the ATF (“Whoa!… Cigarettes and beer are cool.”) I don’t remember that, I don’t remember the 1970s blaxploitation throwback opening credits sequence—yet another example of Tarantino residue I unknowingly inhaled throughout the late-1990s and early-2000s, priming me for the most pivotal theatergoing experiences of my life: the teaser trailer for Kill Bill that played before Gangs of New York at the United Artists Battery Park 16, six Decembers later. I was with my dad both times.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith