Last week, the Maryland Film Festival announced that, starting January 1st, the SNF Parkway Theatre will lay off most of its staff and suspend operations indefinitely. The official line is that the pandemic prevented the film fest’s flagship venue from reaching its potential, with the annual number of paid attendees going from 34,000 in 2019 to a projected 9800 in 2022. That’s a more than 70 percent decrease in attendance. For comparison, the US/Canada box-office gross revenues went from $11.32 billion to $7 billion (and counting, with holiday ticket sales just around the corner), a roughly 38 percent drop.

It’s tempting to attribute this discrepancy to the fact that the Parkway’s a small independent theater, designed to show smaller films that might not attract Top Gun: Maverick crowds, were it not for the festival’s longtime exhibition of big-budget blockbusters, presumably an attempt to attract a wider audience. The truth is that the Parkway has experienced an identity crisis since before the MFF’s longtime director Eric Hatch (who is, full disclosure, a friend) left in 2018. Eric did interesting programming at the Parkway, both new releases and revivals, but organizationally the theater was a mess: a clunky website (that’s no better five years later), ineffective marketing, last-minute screening announcements that were easy to miss, and most of all, persistent rumors that non-profit pencil pushers with no particular affection for cinema were undermining the festival staff’s curatorial judgment. Not long after Eric left, the theater showed its first major release, Aquaman. After that, more often than not, the main auditorium was reserved for similar low-brow entertainment.

I love low-brow. The Home Alone/Die Hard double bill that Eric programmed shortly before his departure was a blast. (I’m also maybe the only person who dug Jurassic World: Dominion, which played at the Parkway last summer.) I just don’t think the decision to cede the main auditorium to major releases and relegate most everything else to tiny screens was smart. I’m sure some people who live in Baltimore City go see big movies there, but many more travel to the Inner Harbor AMC or other big chain theaters in the suburbs, because that’s where you get IMAX screens and 3D glasses and Dolby sound and reclining seats—necessary for something like Avatar: The Way of Water. Whether the festival’s board of directors likes it or not, the Parkway primarily functions as a repertory cinema, the kind of shabby independent theater that’s best for 35mm revivals, 4K restorations, and independent films, around which it might foster a loyal community not unlike NYC’s Anthology Film Archives.

Or the Charles Theatre, right down the street from the Parkway, the festival’s former partner turned competitor. It’s possible that the Charles is faring just as poorly as the Parkway, but I doubt it. They seem to have their business model figured out: new releases that are heavily targeted toward the AARP demo (currently playing: The Fabelmans, The Banshees of Inisherin, Empire of Light) and year-round revivals that cast a wide net for cinephiles. I went to the Charles last Saturday at 11 a.m. to see Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander, and counted over 20 people in the audience, including a few faces I see at almost every screening I attend. That’s a decent headcount for a three-hour Swedish movie on a Saturday morning.

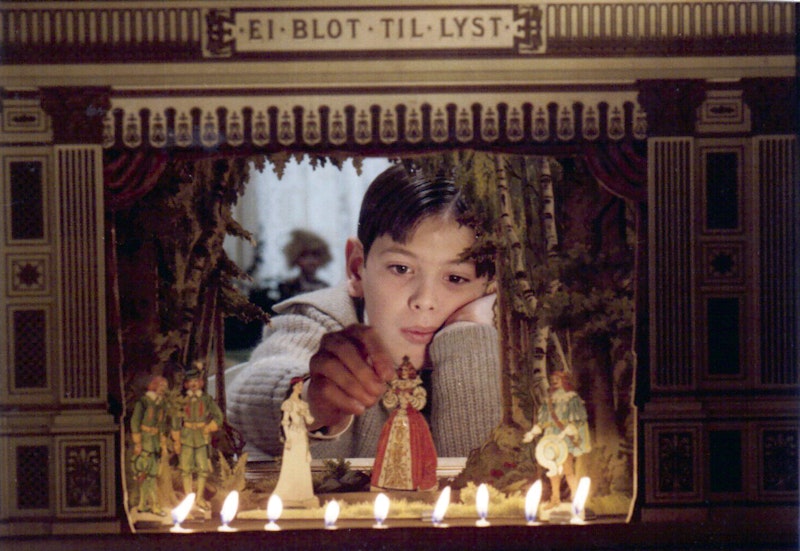

In the darkness of the Charles’ main auditorium, one scene resonated deeper than before. Oscar Ekdahl (Allan Edwall), the director of a small but successful small town theater, addresses his actors at a Nativity play afterparty. “My only talent, if you can call it,” he says, a little choked up, “is that I love this little world inside the thick walls of this playhouse, and I’m fond of the people who work in this little world. Outside is the big world, and sometimes the little world succeeds in reflecting the big one so that we understand it better. Or perhaps, we give the people who come here a chance to forget for a while, for a few short moments, the harsh world outside. Our theater is a little room of orderliness, routine, care and love.” He dies the next day.

This was Bergman’s last feature film, his Tempest—a grand final statement on life, death, and art (though he’d go on to make several more films for Swedish television). It’s not a stretch to read Oscar’s speech as Bergman’s own reflection on his life in film, not just as an artist but also as a film lover (whose VHS collection contains everything from The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant to Anger Management). When Oscar calls the theater “a little room of orderliness, routine, care and love,” he’s speaking for every fledgling arthouse cinema, every little theater that couldn’t show Avatar: The Way of Water even if it wanted to.

Whatever else one might say about it, the long-delayed sequel to James Cameron’s 2009 3D opus demands to be seen in the proper setting, with high frame rate 3D projection and good sound. The plot is mostly a retread of the first Avatar, once again involving a US military invasion of the tropical Pandora (even bringing the first movie’s dead villain back via human cloning), and true to the original, whatever story exists feels secondary to the film’s technical achievements, which include some of the most creative uses of 3D I’ve seen yet. If what Martin Scorsese said about franchise movies is true, that they’re nothing but roller coaster rides, then Cameron is Hollywood’s preeminent roller coaster tycoon.

The Way of Water even feels physically like riding a roller coaster, thanks to its thunderous sound design and fast-moving camera acrobatics. At its most coherent, the effect is immersive in a way few films are. The underwater sequences are so precise in their choreography and camerawork that, for a few brief moments, I kind of forgot that it wasn’t real. An alien shark creature barrels toward the screen and, like those who ducked for cover from the Lumières’ train, I brace myself for impact. That in itself is an achievement.

The action sequences owe their visual clarity to Cameron’s judicious use of high-frame rate (HFR) projection. The controversial method often gives live action movies an unnatural look similar to soap operas, but when applied to Cameron’s mostly animated 3D characters and environments, HFR does just the opposite, lending the alien world texture and sensual stimuli that was largely absent from the first Avatar. However, the franchise exists with one foot on earth and one in Pandora, and the Roger Rabbit mix of live action and animation forces Cameron to alternate between 24 and 48 frames per second. The result: one shot is a crisp plunge through tall trees on the back of a mountain banshee, and the next is a strobing tracking shot of a feral boy running through the jungle below (anyone trying to dissuade themselves that pedophiles control Hollywood will take no comfort in the teenage Spider, naked except for a loin cloth, the worst character-as-plot-device since Elliot Page in Inception).

These big aesthetic swings, from simulator ride to video game cutscene to motion-flow TV, should bother me, but compared to the glossy, hyper-processed, color-corrected sheen of most modern cinema—franchise or independent, digital or celluloid—they’re endearing. The Way of Water’s mercurial approach to montage, the way the shots sometimes feel disconnected from one another, as if they’re wholly separate materials Cameron and his team have painstakingly stitched together, makes it feel more like a labor of love than average movies.

If The Way of Water is a success on a technical level, it leaves much to be desired as a narrative—a finely-made roller coaster with an extremely familiar track. If there’s one thing that prevents an entirely immersive experience, it’s the nagging feeling that we’ve seen this story before, by others (Dances With Wolves, Come and See, and Apocalypse Now all get quoted) and Cameron himself, with obvious callbacks to The Terminator, T2, Aliens, and Titanic—all of which are better movies, mostly on account of stronger scripts.

The sentimental moments, something that Cameron does very well (the final thumbs up in T2, or the old couple holding each other in bed while the water rises in Titanic), miss as often as they hit. On the plus side, there’s the wonderful friendship between Lo’ak (Britain Dalton) and the giant cetacean creature Payakan, who bond over their shared experience as black sheep in their families. These heartfelt scenes are a relief from the dominant favorite son conflict that predictably ends in death, the kind of cookie-cutter family drama that sneaks its way into every animated movie these days.

When the time came for the family to mourn its departed loved one, Simon Franglen’s orchestra swelling in the background, it felt phony. I thought back to the previous day’s screening of Fanny and Alexander, one scene in particular: after Oscar dies, his children (Pernilla Allwin and Bertil Guve) wake up in the night to screams. Deep, resounding, sustained cries, the sound of unimaginable pain, like someone strapped to a medieval iron chair. We follow Alexander through a giant sliding door, Fanny close behind. Across the hall, through another open door, we see their mother (Ewa Fröling) pacing around the body of their father, each successive cry burrowing a little deeper into the hearts of her children who, like us, can only look on helplessly, tears welling in their eyes.

While critics fawn over The Way of Water, putting those Disney PR dollars to work, it’s good to remind ourselves that scenes like these are the real reason we go to the movies—to feel something, to share a universal truth, to commune with others over a common experience, even one as painful as losing a family member. Roller coasters can be lots of fun, and as roller coasters go, you’re not going to find a better one than The Way of Water. By all means, see this movie. It’s pretty good! But don’t go into it expecting great cinema, no matter what the Disney PR department tells you. Want great cinema? Go see a Bergman film.

Better yet, if you’re in Baltimore, go to the Parkway and see its Hard Candy Christmas series before it closes. Buy snacks and drinks. Tip the staff a little extra. It’s the least we can do for those who give our little world the orderliness, routine, care and love it deserves.