It’s hard to imagine the 1972 film Prime Cut getting made today. The film stars Gene Hackman as a crime lord in Kansas City who runs a slaughterhouse as a cover for a drug and prostitution operation. Hackman, whose character is named Mary Ann, has neglected his debts with a Chicago crime clan, so an enforcer (Lee Marvin) is sent to collect. Combining gangsters, disturbing slaughterhouse footage, un-ironic scenes of Middle American wholesomeness, and the appearance of a young Sissy Spacek, Prime Cut is one weird movie.

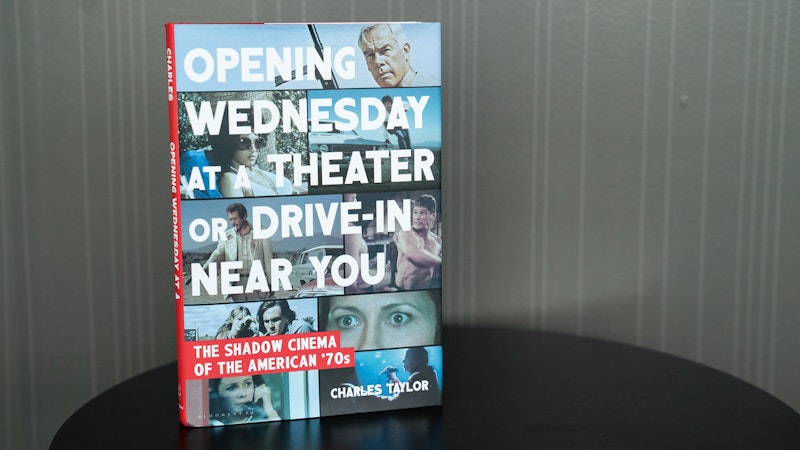

It’s also a completely original one, and a film with ambiguity and adult themes despite its B-movie tone. Prime Cut is one of the films explored in critic Charles Taylor’s wonderful new book, Opening Wednesday at a Theater or Drive-In Near You: The Shadow Cinema of the American ‘70s.

Prime Cut is an example of what Taylor calls the “shadow cinema” of America in the 1970s. The shadow cinema was reserved for films in the spot between greats like The Godfather or The French Connection and exploitative grind house grunge. “For me, the staying power of these movies has to do with the way they stand in opposition to the current juvenile state of American movies,” Taylor writes.

“The infantilization of American movies that began in 1977 with the unprecedented success of Star Wars has become total. Mainstream moviemaking now caters almost exclusively to the tastes of the adolescent male fan.”

The shadow cinema wasn’t great. Taylor breaks down the genres as horror movies, biker pictures, nudie teasers, women’s prison pictures, moonshiner documentaries, phony documentaries, and Eurosleaze exploitation pictures. But the films offered an ambiguity that didn’t “hold the realities of human behavior hostage to ideology.” A character could have an abortion yet also feel terrible about it. Films could love and resent America and capitalism. Good protagonists bit the dust. In these films Taylor found “the connection to the world, and to real-life emotions—not to mention the craft—that today’s blockbusters and remakes and churned out franchises work so hard to avoid.”

Opening Wednesday examines 15 movies from the 1970s, among them Prime Cut (1972), Vanishing Point (1971), Cisco Pike (1972), Eyes of Laura Mars (1978), Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), Aloha, Bobby And Rose (1975), Ulzana’s Raid (1972), American Hot Wax (1978), and the Pam Grier blaxploitation vehicles Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974).

“By reducing mass slaughter to assembly line proficiency,” Taylor writes of Prime Cut, “[director Michael] Ritchie wickedly exposes the manner in which the continuing deaths of American soldiers in Vietnam was sold to the public, but in the guise of a mob-enforcer tale. Prime Cut is a brutalist satire of the America the silent majority was trying to hold on to.” Yet those Americans are not mocked in Prime Cut. This is evident, writes Taylor, in a long sequence at a country fair “in which Ritchie and cinematographer Gene Polito simply take in the sights and the people.”

There’s a marching band, souvenirs, a carousel, a hog-tying competition, a pie-eating contest, “kids pitching rings around bottle necks or tossing baseballs to win a stuffed animal or just laughing happily on rides. It looks like a pleasant way to spend an afternoon, and it isn’t presented as a lie… This isn’t a rotten or corrupt America, and it isn’t a clichéd one. It’s an America that, in the midst of Vietnam and the Nixon years, still exists—and not as relic.”

In shadow cinema Taylor sees a bracing ability by the filmmakers to level with the viewer, who’s treated not only as a thrill-seeker but an adult. In his essay on actress Pam Grier and the legacy of 1970s blaxploitation films, Taylor notes that Grier was not seen or appreciated by the majority of Americans in the 70s due to racism, but was honored by Quentin Tarantino, whose Jackie Brown (1997) is now considered a minor classic and has many attributes of shadow cinema. Free of the broad and clunky scripts of the 1970s, Jackie Brown “allows Grier the uncertainty of an adult entering middle age, no longer sure she has the strength to start over.”

The films in Opening Wednesday are free of the dark pessimism of Easy Rider (1969) and Chinatown (1974) and the happy endings and folksy moralizing of more mainstream movies. To show this, Taylor examines the different endings of Easy Rider and Vanishing Point. In Easy Rider, the two hippie bikers, played by Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, are blown away by redneck America in an act of howling violence. In Vanishing Point, a solitary driver simply named Kowalski committees vehicular suicide after a long drive across America. Yet before Kowalski drives his car into a wall he smiles. Taylor: “It’s the smile that comes from having eluded expectations, memory, despair, from—just for a moment—doing what you want for no other reason than because you want to.”

How great would it have been if Han Solo had gone out that way?