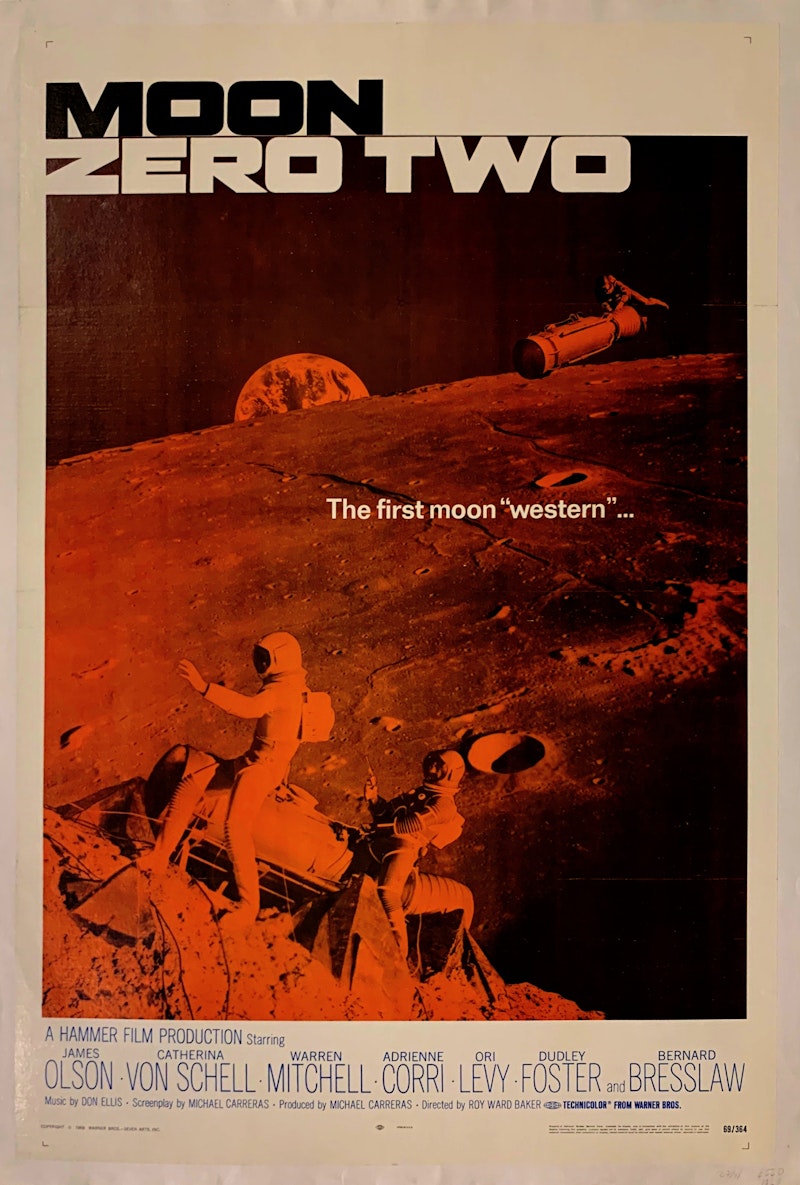

Nineteen-Fifty-Two. That was the year when outer space met The Old West. More accurately, that’s when the eccentric comic book company Charlton began publishing Space Western, one of the first major sci-fi works to meld two of pulp’s fave genres. Space western narratives would rarely be revisited after the Space Western comic ceased publication in 1953. The hybrid genre’s greatest revival came in 1969 with Hammer Studios’ film Moon Zero Two. While Charlton’s space western comics were surreal but mostly kid-friendly, Moon Zero Two owed a great debt to the erotic sci-fi craze kicked off by Barbarella, adult-oriented spaghetti westerns, CBS’ Gunsmoke and Wild Wild West series, and other films and TV shows that satirized, tweaked, and re-furbished classic western themes.

Like the earthly settings in Altman’s McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Peter Fonda’s The Hired Hand, and Phillip Kaufman’s White Dawn, Moon Zero Two’s lunar frontier is a place where the line between love and lust is non-existent. Beneath the solar system’s sprawling firmament a perilous grab for economic prosperity and natural resources leaves people emotionally and mentally drained. Within controlled confines of the moon’s busy spaceport introspection is impossible and morality becomes hopelessly obscure.

The film’s plot has a few surprising turns, but for the most part Moon Zero Two’s spectacular visuals are what make it an important work. A wacky cartoon opening sequence sets the tone with Russian and US astronauts careening across the moon’s surface, chasing and bashing each other over the head with their national flags. The image prepares viewers for director Roy Ward Baker‘s blasphemous take on sci-fi western concepts: lunar bar flies guzzling poisonous concoctions made from distilled rocket fuel; a space station sporting crass commercialism and high tech luxury suites; hedonistic astronauts hooked on cheap thrills; a power-crazed billionaire trying to buy the dark side of the moon. These were the consequences of a decadent space life modeled after the early days of America’s robber barons and Roaring 20s as well as The Gold Rush and The Westward Expansion.

There are extended sequences where the film’s protagonists (Catherine Schell in a proto-Space: 1999 role as Clementine Taplin and TV stalwart James Olson as the jaded/Han Solo-ish pilot Bill Kemp) make a dangerous trek to the dark side of the moon. These scenes are Moon Zero Two’s best, most poetic moments. Feeling unfulfilled and purposeless in the confusing/fast paced future world, Taplin and Kemp share ruminations on fear, nostalgia, and self-discovery. Inevitably their soul-searching blooms into romance. Their dimly-lit interactions gradually become sweeter and more intimate as the 48-hour drive rolls on. Extremes of awkwardness and distrust turn to mutual attraction during their search for the ominous ruins of a mysterious mining operation, a site where Taplin’s brother has gone missing.

For most of the film we’re treated to an eye-popping spectacle not unlike many other big budget Vietnam-era sci-fi flicks. The interior design of the luxurious spaceport is illuminated by a gaudy glare of fluorescent light, loud colors, ticket officers and security guards in revealing costumes, and other post-Barbarella glitz. Moon Zero Two’s production design predicts everything from the cantina scene in Star Wars to the swinging utopia of Logan’s Run to the commercial dystopias of Running Man and Total Recall. The lunar outpost milieu is barely more than a chintz-blasted rest stop along an interstellar super highway.

A strong juxtaposition is created by the crowded interior spaceport scenes and the remote exterior moon shots. Far from the spaceport noise, the quiet hum of the rusted moon buggy dominates the soundscape as Taplin and Kemp trundle along cloaked in darkness. As they return the film reaches its climactic Old West shoot out. The lighting becomes gaudy again, the cast swells back to a large size, and modern spaceport conveniences reclaim their brutal dominance. The return to civilization brings death, tragedy, and betrayal. Here we find the iconic opening strip tease from Barbarella echoed in a reverse negative form. While the generous pleasures and passions of outer space unleashed the sensuality of Jane Fonda’s sexual super hero, the stuffy synthetic spaceport environments of Moon Zero Two only unleash a cold destructive power madness.