“We blew it.”

Some say those words at the end of Easy Rider marked the end of the 1960s in the United States. They were prescient for the years ahead—shifts that began in the 1960s continued and reverberated throughout the country well into the next decade and beyond. Hollywood was no exception. The success of late-1960s counterculture movies like Easy Rider and Bonnie & Clyde heralded a new age for American motion pictures, as major studios hired young writers and directors to try and recapture the spirit of those cultural touchstones with contemporary characters fit for the times. “New Hollywood” films such as The Conversation, All the President’s Men, and Nashville saw critical and cultural success, as their lead roles’ journeys through uncertain times acted as a reflective point for modern audiences.

Though not as acclaimed, other films from the 1970s are equally illustrative of the decade’s artistic, societal, and political developments, primarily depicted through their unsettled male leads: the struggling artist in Cisco Pike; the convoluted crossroads in Night Moves; and the political deflation of The Big Fix.

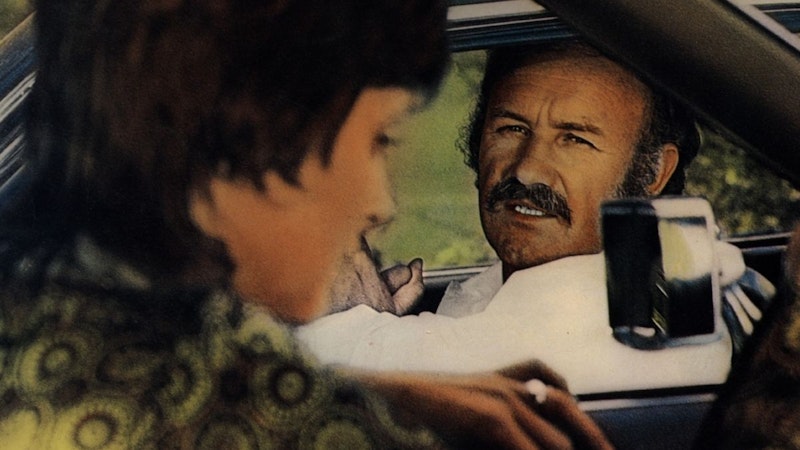

Released in 1971 and directed by Bill Norton, Cisco Pike is one of the many small-budget, counterculture-adjacent dramas made in the wake of Easy Rider’s success. The titular Cisco is a former folk-rock star (played by an up-and-coming Kris Kristofferson) looking to get back into the music business. His reasoning is clear from the opening scene: after two drug arrests, Cisco is going clean, since a “third strike” would mean years of jail time. His dreams of returning to the spotlight are derailed when crooked cop Leo Holland (Gene Hackman) appears at Cisco’s door with a plan to sell 100 kilograms of stolen marijuana in a weekend. Cisco’s hesitant to break the promise he made to his girlfriend Sue (Karen Black) and to himself to quit dealing; however, faced with Holland’s offer to alter his arrest record, Cisco agrees and moves across Los Angeles to sell the pot without Sue finding out.

Cisco reluctantly slides back into his old habits, making calls and offloading the drugs with a skill only gained through experience. Cisco also struggles to juggle his various clients and Leo’s demands while avoiding Sue, causing him to become more paranoid and irritable as the weekend drags on. Even the arrival of his former bandmate turns from a joyous occasion to a tragic one: Jesse (Harry Dean Stanton) is strung out, dispirited, and impotent. The symbolic return of his past as a broken and defeated man throws Cisco’s bleak situation into sharp relief. The movie’s soundtrack is mostly Kristofferson’s own laidback country music, laying quiet melancholy under Cisco’s troubles.

It's apparent throughout Cisco Pike that most of Los Angeles recognizes him as more of a pusher than a musician. In a scene at a recording studio, his new demos are deemed “weird” by an old music buddy; Cisco’s introspective brand of singer-songwriter folk music isn’t as compelling as more straightforward rock 'n’ roll. Like everyone else he meets, they’re far more interested in the weed he keeps in his guitar case. As chaos ensues at the film’s climax and Cisco is effectively forced out of town, it becomes clear that any hope for a career revival has already faded.

Arthur Penn’s sun-drenched neo-noir Night Moves focuses on a man whose fame in 1960s Los Angeles has similarly come and gone. The film stars Gene Hackman as Harry Moseby, a former Pro Bowl-caliber football player who now spends his days as an independent private detective. Despite a lack of real income or big clients, Harry shows a passion for his newfound profession; this sentiment isn’t shared by those around him, including his wife Ellen (Susan Clark). Early on, he tails her and discovers she’s having an affair. Harry’s clearly upset by her infidelity but struggles to confront Ellen, deciding instead to trail her lover and investigate him first. His impulsive actions display his frustration and uncertainty in both his career and personal life, further straining an already fraught situation.

Facing a deteriorating marriage, Harry bores full-time into his work. His newest case is for Arlene Iverson, a former Hollywood actress hanging onto her days of semi-stardom with a desperate veneer of wealth and glamour. She’s looking for Delly (Melanie Griffith), her runaway daughter whose trust fund is Arlene’s only source of income. The premise is cynical, as is the chase: through speaking with various stuntmen involved with both mother and daughter, Harry tracks Delly to the Florida Keys. She’s been hiding out with her stepfather Tom and his partner Paula, who are much less controlling than Arlene. This relaxed approach is appealing to the liberated teenager, though that carefree nature extends to Tom’s feelings towards his own daughter. Tom’s uninterested in the case until Harry brings up the police, which scares Tom into compliance. Delly’s unwilling to return to the West Coast, but a traumatic incident involving an underwater cadaver shocks her into going back. Tom’s aloof behavior and the conspicuous corpse further Harry’s suspicions that he may have stumbled upon a more sinister situation.

With the case seemingly solved, Harry shuts down his agency and patches things up with Ellen. Nevertheless, the entire sordid affair continues to make Harry uneasy, and the closing act becomes an overwhelming series of events that force him to return to Florida. Hackman, in the middle of an impeccable run of roles during the decade, gives one of his most nuanced performances here. As Harry’s romantic and professional struggles mount, it begins to show in Hackman’s body language and worn, aging face, particularly by the very end, way out at sea. The disparate threads that hang throughout the film finally tie together into a larger, complicated conspiracy that steer Harry to an illegal smuggling operation. He may have pieced the mystery together, but the outcome leaves him feeling bewildered: as he takes a boat to meet with Tom’s smuggling contact, he scornfully remarks to Paula, “I didn’t solve anything. This fell in on top of me.” In these final moments, the full weight of the case collapses onto Harry: after weeks of detective work, the convoluted results are unsatisfying.

Night Moves ends with Harry gravely wounded, unable to drive the boat out of its circular path on the open sea. It’s a powerful image, though not subtle. That the central mystery of Night Moves isn’t solved by the detective’s sharp logic or intuition, but mostly through coincidence and happenstance, is its most enduring image. Further, As with Richard Nixon and Watergate, in the face of overwhelming evidence of criminal wrongdoing, the end results are rarely satisfying.

The politics of both decades take center stage in Jeremy Kagan’s The Big Fix. This 1978 comedy-thriller coincides with the end of an era as a generation ages into the settled, suburban lifestyles they once disdained. For Moses Wine (Richard Dreyfuss), that move has proven difficult. Once an activist at UC Berkeley in the mid-1960s, he’s now a divorced father of two working as a private investigator to pay child support. Moses feels like a sellout and still holds onto his past; even his car, an older Volkswagen convertible, is symbolic of the bygone era he cherishes. When he’s approached for a job by a former flame from his Berkeley days, Moses is yanked from the haze of his daily life and reminded of the times he remembers most fondly.

The wistful memories quickly fade when Lila (Susan Anspach) reveals she’s there on behalf of Miles Hawthorne, a banal Democratic candidate running for governor of California. Their concern is a series of flyers that suggest a former radical leader supports Hawthorne—a bad look to the wealthy, conservative voters in Orange County the campaign is courting. Both characters have lost their youthful activism, and it directly informs their current positions: in an early scene, Lila tries to convince Moses to help investigate the source of these flyers, and she calls him cynical. His pithy retort, “the Sixties are over, Lila,” might be true, but it’s obvious that Moses remains unconvinced of his own words.

Eventually, Moses takes the job and looks for the source of the flyers. His investigation brings him into contact with characters across the ideological spectrum, representative of the staid and toothless political landscape of the late-1970s. Many members of the so-called “Underground” he meets are either imprisoned, missing, or severely marginalized in their political impact. This wasn’t far off from reality—in the post-Vietnam War era, protests on campuses atrophied.

Even Howard Eppis (F. Murray Abraham), the elusive radical Moses has been tracking, has settled down in the Hollywood Hills with a family, a cushy advertising job, and a pool. It’s telling that Eppis is a paper-thin analog to real-life activist Abbie Hoffman, who likewise went into hiding in the mid-1970s, exchanging his political influence for individual peace and safety (he’d later serve prison time and return to activism after the film’s release). Eppis, content with trading in his radical ideas for suburban life, explains to Moses that their sensibilities are simply not in vogue with the younger generation: “People got bored, style changed, hair got shorter... it was no longer chic to be radical.”

These films aren’t that similar in tone or plot, but all three convey the depressed, transitional dynamics of the 1970s through their respective leading men’s willingness (or lack thereof) to change with the times. For Cisco, this provides the constant tension he faces throughout the film—his resolve to move towards a brighter future is perpetually tied down to his drug dealing past in a stagnant city. Harry finds conviction in his work as a private eye—but, in the face of a declining marriage and fading influence, a seedy cross-country case wears him down into a cynical and demoralized man. For Moses, his unwillingness to let go of the past is holding him back for most of The Big Fix. His ex-wife Suzanne (Bonnie Bedelia) calls him a “would-be Marxist gumshoe” in a heated argument, and bluntly frames their differences: “I’m letting go of all my past bullshit, obviously you’re still stuck in it.” Solving this case becomes as much about uncovering the truth behind Howard Eppis as finding the means to overcome the nagging nostalgia that prevents Moses’s own personal progress.

In an emotional scene in Night Moves, as Harry confronts Ellen’s lover, he goads the detective to “Take a swing at me Harry, the way Sam Spade would!” Harry, along with Cisco and Moses, are far afield from the Sam Spades and Philip Marlowes of old Hollywood. These films aren’t only representative of how people can fall behind the ebb and flow of rapid societal shifts, but places and industries as well. Los Angeles, the setting for all three films, changes little from 1971 through 1978. They paint a melancholic portrait of a city hungover from the optimism of the 1960s, before its decadent resurrection in the 1980s.

Similarly, Hollywood struggled to find its footing in the wake of the counterculture, only to find massive success with the inauguration of the blockbuster era at the close of the decade. Even with the star power of their leads in Kristofferson, Hackman, and Dreyfuss, none of these three films were financially successful or critically praised upon release. Today, they’re insightful glimpses into the cultural landscape of the 1970s and emblematic of the mood of the times—conflicted, frustrated, and ultimately reconciled with the inevitable.