Every so often, a new movie about the life of Jesus appears. Sometimes it works, sometimes not, but ponder this pitch for a new project: Channing Tatum is a big hot Jesus. The messiah spent the years between his miraculous birth and redemptive reappearance working out at a boutique gym and drinking Muscle Milk. Our Jesus is an Adonis, and as a matter of fact we wrote the John the Baptist part with the Rock in mind. As it turned out, once we got the stars on board, money was not a problem. Unfortunately, the critics' consensus on the newly-released Crucifixion of Magic Mike is that it’s unintentionally comical in its extreme incoherence, and liable to offend anyone who identifies as a Christian.

The Italian Renaissance is usually portrayed as the height of human artistic achievement, a moment of culmination. Some people think that art's been in decline ever since. (Personally, I prefer my Renaissance northern: I'm going with Van Eyck and Dürer over Uccello and Raphael.) There are many ways to describe the basic philosophical and spiritual orientation of the Italian version, but central to any account is the revival of pagan antiquity and the attempt to reconcile it with Christianity. Obviously, that leads to impressive art: Leonardo and Botticelli, Donatello and Michelangelo. However, the value systems and mythologies are howlingly incompatible with one another, and I don’t think they’re successfully reconciled. Nowhere is this tension more extreme than in Michelangelo.

Michelangelo served the Papacy at what is perhaps its darkest and most decadent era. Even as he was decorating the Sistine ceiling and redesigning St. Peter's on the grandest of scales, Borgias and other Popes were assassinating one another, throwing orgies in the Vatican, implanting the women of the Italian peninsula with their illegitimate children, sending their armies here and there, and financing it all by selling spots in heaven to rich people. As Michelangelo painted, northern Europe went into paroxysms of revulsion at Rome, which Luther called "the whore of Babylon" and "the anti-Christ," partly because of the encrustation of decoration for which Popes had been draining the coffers of Europe and commissioning the artists of the High Renaissance.

Meantime, the revival of ancient learning in the Renaissance led to "humanist" philosophy, which struggled mightily and with mixed success to bring together Aristotle and Jesus, or Homer and the Gospels. From Aquinas and Dante to Ficino and Erasmus, the efforts were prodigious. But despite what anyone wanted to believe, nothing could be more obvious than that the belief systems are at their core irreconcilable. The ancient Greeks and Romans counted pride as a virtue; Christians made it a deadly sin. Homer celebrated the homicidal berserker rage of mighty Achilles; Jesus told you to beat your swords into ploughshares. Christianity from Augustine taught self-abnegation before God, humility, poverty; paganism deified emperors and made their gods avatars of greed or lust. Pagan antiquity was sexually frank, its practices multifarious, its gods bisexual adulterers; Christian monks took vows of chastity and taught that sex was for procreation.

Indeed, one of the motivating forces for the establishment of Christianity was a repudiation of Roman values in many or all dimensions, what Nietzsche called "a slave rebellion in morality." The gods of the Roman masters, killing and fucking their way through myth and legend, were held to be demons. Christian values were developed explicitly in opposition to all of that.

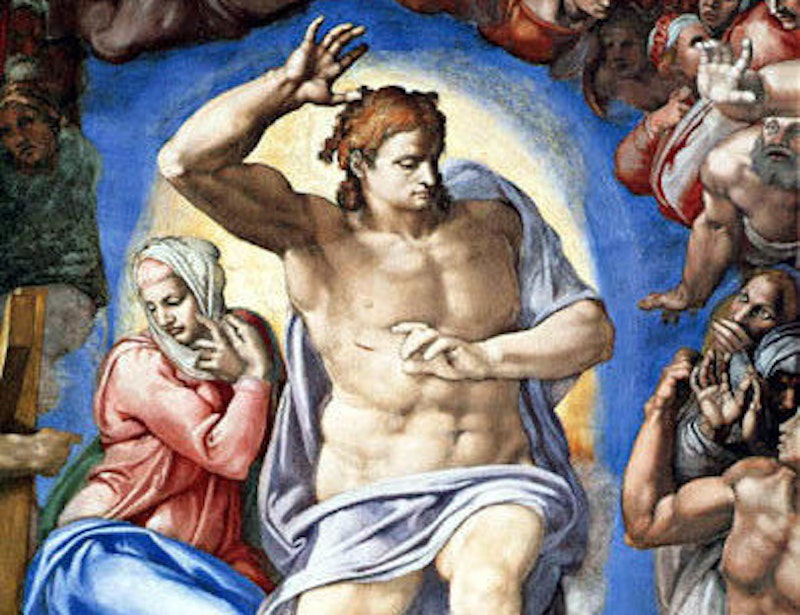

Michelangelo tried to participate in the invention of a religion that identified Jesus with Apollo. But that's just a very confused cult that worships a chimera. Sandro Botticelli—he of the Birth of Venus—was tortured by this tension, as well he should’ve been. You can't live both systems of value, or deploy both iconographies simultaneously. I'm not saying which way to go on this; I'm just saying that "both" is not one of the possibilities.

Great art can be made under the auspices of an incoherent belief system or a crackpot cult, and often has been. I don't deny the greatness of some of Michelangelo's sculptures, though the blank male-modelhood of the David leaves me indifferent. There's no denying the Pietá or the bound slaves emerging from their rock prisons. But I do object to the painting. I don't think he's a master colorist; it tends to float orange and simplistic. He famously favored big chunky bodies; even his women look like Channing Tatum. In terms of composition, he has neither the purity of Raphael nor the subtlety of Leonardo; that Last Judgment is a mess. I'm often left with an impression of blockiness, clumsiness, or mere oddness.

Those are subjective declarations, I suppose, and if you love the Sistine ceiling, go ahead and love it. Frankly, it doesn't strike me as a work that could really inspire love: Michelangelo is more impressive than inviting overall, more formidable than graceful. Whether or not they're beautiful, however, the paintings of Michelangelo represent a pagan Christianity, a sexualized asceticism, a prideful humility, and a warlike religion of peace. They show you why a Reformation was necessary, if for no other reason than to try to force Europe to make some sense.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell