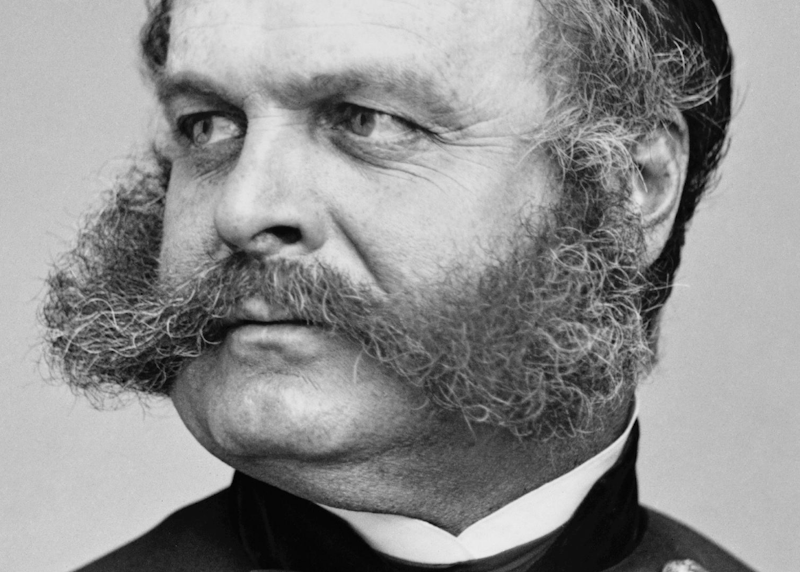

On January 25, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln replaced General Ambrose E. Burnside as commander of the Union Army of the Potomac with General Joseph Hooker. Burnside, from whose elaborate facial hair configuration the term “sideburns” is derived, had his fate sealed when Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army crushed his own forces at the Battle of Fredericksburg in Virginia the previous December, which the President had been desperate to win.

The Union Army’s technical victory at the Battle of Antietam in Maryland in September, while not tactically significant, had given Lincoln enough confidence to go ahead with the Emancipation Proclamation, signed on the upcoming New Year's Day, 1863. This, he thought, could keep the French and British from recognizing the Confederacy and entering the war. Since the bloody battle in Maryland, however, the Union Army had lost momentum. Lincoln felt he needed a win in Fredericksburg to bolster public confidence in a war many feared had stalled, but he got just the opposite.

Burnside, once a railroad executive, was new to his position when he reached Fredericksburg. Lincoln appointed him after he'd lost confidence in his predecessor, General George McClellan, who'd failed to pursue and destroy Lee's army during its retreat to Richmond in the aftermath of Antietam, the deadliest one-day battle in all of American military history. McClellan, who’d earned the sobriquet “Little Napoleon” after winning a series of small battles in western Virginia, was a meticulous planner, but too cautious for the anxious president. Even when he enjoyed a numerical advantage, the general was often loath to attack the Confederate Army, having received faulty intelligence that overestimated the enemy's strength. McClellan, throughout the tenure of his command, was always fighting an enemy that was much weaker than he reckoned it was.

Back in June, Confederate President Jefferson Davis tapped Lee to replace Joseph E. Johnston, who’d just been badly wounded in the Battle of Seven Pines, to be commander of the Confederate Army defending Richmond. Lee kept his command until the end of the Civil War, but his appointment was greeted with much skepticism at the outset. As the general from Virginia took the reins of the Rebel army, McClellan and his 100,000-soldier army was planning to lay siege to the Confederate capital. Lee silenced his critics in late June with his brilliance in winning The Seven Days Battles and sending McClellan’s forces into a retreat down the Virginia Peninsula.

McClellan had given Burnside command of the Ninth Corps at The Battle of Antietam, where he received criticism for his slow pace in crossing what is now called "Burnside Bridge" over Antietam Creek, a task that was critical for strategic reasons. While some feel McClellan tried to make Burnside a scapegoat out of bitterness, there was also speculation that Burnside's inability to quickly take the bridge from outnumbered Confederate forces allowed Lieutenant Gen. A.P. Hill's speedy Light Division to come up from Harpers Ferry and counter the Union advance. Hill, who ranked with James Longstreet and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson as Lee’s most trusted generals, was to die in battle at age 39 outside of Petersburg, Virginia in April of 1865.

Five days after Burnside replaced McClellan, Lincoln approved the general’s plan to take Richmond, unaware he was paving the way for one of the Confederacy's greatest victories. The plan involved Burnside taking his army 40 miles to Fredericksburg, located on the Rappahannock River. Subsequently, the troops were to advance south to Richmond before Lee's Confederate Army, which was in Culpeper blocking Union advances, could stop him.

Burnside, however, found himself flummoxed when he arrived at the Rappahannock, as a bureaucratic snafu had caused a two-week delay in the arrival of the necessary pontoon bridges. By the time they got there, snow began falling, creating further complications. While these setbacks allowed Lee to ready his troops, that didn't deter Burnside from his plan to cross the river. Lincoln was applying so much pressure that more than purely military considerations were dictating his decisions at this point. The Confederates were able to find advantageous defensive positions where they mounted artillery pieces and waited. Burnside ordered multiple attacks against those entrenched Confederate positions on the high ground of Marye’s Heights, generating more than twice (12,700) the number of casualties among his own troops than the Confederates sustained.

On January 20, 1863, with the two armies still facing each other across the Rappahannock River, Burnside decided to mount another attack. As it got underway, heavy rain and strong winds kicked in. “The whole country was a river of mud,” wrote one soldier. “The roads were rivers of deep mire, and the heavy rain had made the ground a vast mortar bed.” What was soon to be known as “Burnside's "Mud March" was abandoned the next day. On the other side of the river, Confederate soldiers taunted the Federals by erecting signs saying “Burnside’s Army Stuck in the Mud” and “This way to Richmond.” Burnside attempted to boost morale by issuing liquor to the soldiers after the fiasco, which led to entire regiments fighting each other.

Five days later, Lincoln accepted Burnside's resignation. Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker took his job, and held onto it until his surprising defeat in the Battle of Chancellorsville in June, 1963 prompted his resignation. George Meade, who succeeded him, was successful in crippling the Confederate Army at Gettysburg, but he was widely criticized, like McClellan after Antietam, for allowing Lee’s weakened troops to escape into Virginia.

Richmond wouldn't fall until April, 1965 after a long siege led by Meade's successor as general-in-chief, Ulysses S. Grant. Jefferson Davis evacuated Richmond with his cabinet and headed to Danville, Virginia on the Danville train, where they attempted to set up a temporary government. That's the same train Virgil Caine, the narrator of The Band’s masterpiece, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down” worked on. Old Dixie’s days were numbered by the time that train pulled into the Danville station on April 2, 1865. In one week, Lee would surrender in the parlor of Wilmer McLean's home near Appomattox Court House.