In May 1939, Erich Silber, my future father, then 14, his eight-year-old brother Robert and their parents left behind what had been a charmed life in Vienna, Austria, fleeing with virtually no money and possessions to an impoverished, faraway country, the Dominican Republic. It was a narrow path out; had things gone slightly differently, they’d have been Jews trapped in the Third Reich.

My grandfather and grandmother were born in the 1890s in the Galicia region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; following shifts in borders, their hometowns are now in Ukraine. They each went to Vienna to study medicine (and in her case, later dentistry; credentials unusual for a woman). They treated wounded soldiers in World War I, my grandfather serving as a lieutenant in the army’s medical corps. Around that time, they changed their names to fit the Austrian mainstream. She went from Miriam or Myriam to Maria. He switched from Abraham to a name he’d later regret: Adolf.

“Until 1938, ours was not a Jewish world,” my uncle Bob wrote decades later in an unpublished memoir. The family read German poets, listened to Italian opera and socialized with non-Jews and Jews alike. They lived in a large apartment that included areas for my grandfather’s office as a general practitioner and my grandmother’s dental practice. My grandfather worked long hours, made house calls and was known to turn down payment from the cash-strapped. The majority of his patients were non-Jewish, and he joked that they “complained less.”

Such assimilation provided no protection after the Anschluss, Nazi Germany’s annexation of Austria in March 1938. Erich and Bob were spat upon in school. A young doctor showed up to take over the medical practice, and the family was ordered to leave its apartment and move to a Vienna neighborhood designated for Jews. They shared an apartment there with relatives.

Shortly before Kristallnacht, the November destruction of synagogues and Jewish properties across the Reich, my grandfather was arrested and jailed, along with other Jewish doctors. My grandmother collected signatures from patients avowing his good character. She also engaged a sympathetic lawyer named Schartel, who was an officer in the Schutzstaffel, the paramilitary organization that would be central to the Holocaust. “How he was an SS lieutenant and a nice guy, I don’t know,” my father said long after, in an interview with my brother.

My grandfather’s jailers were not so nice. He later told the family that he once overheard what was happening a few cells down, where another imprisoned doctor’s son had been brought in and beaten to extract the doctor’s confession. Fearing that his own sons would be subjected to similar treatment, my grandfather tried to hang himself with his belt.

With Schartel’s help, my grandmother appealed at Gestapo headquarters for her husband’s release. The answer was that he’d be released only if the family obtained a foreign visa to leave the Reich. They insisted it had to be for an overseas country, not somewhere in Europe.

Getting such a visa was difficult, as few countries anywhere were receptive to Jewish refugees. The U.S. was holding to a system of low immigration quotas amid the lingering Great Depression and the isolationist “America First” movement. In July 1938, at President Franklin Roosevelt’s request, 32 nations convened in France for the Évian Conference on the refugee issue, but the discussion there was noncommittal or worse. “As we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one,” said the delegate from Australia.

There was one exception. The Dominican Republic’s delegate announced that the small Caribbean nation would accept up to 100,000 Jewish refugees. This humanitarian gesture had grim motivations. An influx of Europeans could help the Dominican dictator, Rafael Trujillo, toward his goal of making the population lighter-skinned. It also would divert attention from his recent massacres of Haitian migrants. Plus, the refugees would be charged a hefty entry fee.

The latter point meant that the family’s departure would require a foreign sponsor to send the required funds, in U.S. dollars, to the Dominican Republic. As it happened, a telegram was received at the Jewish committee in Vienna from its counterpart in New York, saying that the relatives there were worried about the family and wanted to know how they could help. The committee asked if they should reply, but my grandmother said she would do that herself.

She and my father composed a grateful telegram to Franz Goldenberg, a wealthy concert pianist who was a distant relative. They opened with the word “Lebensrette” (Lifesaver) and explained how they were trying to secure an exit visa. Goldenberg got this note and provided the needed funds. After the war, the family discovered a fortuitous mix-up: the initial message hadn’t come from Goldenberg but from other relatives, ones much less able to send money.

And so, my grandfather was released, and the family was able to leave, taking a train from Vienna to Hamburg, where in early May they joined a small group of passengers on a cargo ship named the Frida Horn that was headed to the Caribbean. The crew was mostly unfriendly. As the ship crossed the Atlantic, the captain announced that, if war broke out, his orders were to scuttle the ship rather than let it be captured. The Jews worried they wouldn’t be let onto the lifeboats. As it happened, the outbreak of World War II was still over three months away.

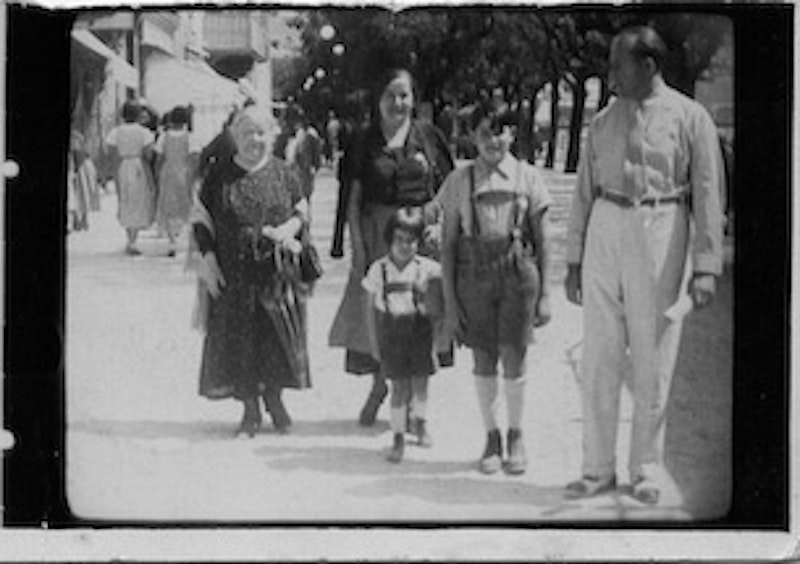

The family disembarked on May 25, 1939 in Santo Domingo, the Dominican Republican’s capital, renamed Ciudad Trujillo. When they opened a crate of their few un-confiscated possessions, there was an expensive Persian rug at the bottom. Some relatives, before their own departure, had stashed it in the family’s crate; had this smuggled valuable been discovered by the Nazis, the consequences would’ve been disastrous. Instead, our family sold the rug to a dealer, who resold it to Trujillo, and the heirloom ended up in the presidential palace.

The number of Jewish refugees who made it to the Dominican Republic was at most in the low thousands. The four of our family lived there until 1946, coming to the U.S. after the war. They were allowed in under the Austrian quota, ironic considering the history. My grandfather died in 1950 and my grandmother in 1963: I never met them. Erich, my father, was a businessman with wide connections in Latin America. He passed away in 1990. Uncle Bob, whom Erich helped put through medical school, became a noted figure in hematology, living until 1998.

Family money from before the war long sat in a Swiss bank account, forgotten. Swiss banks made it difficult for displaced people to retrieve their funds after the war. At the turn of the 21st century, a tribunal was set up to adjudicate claims to such accounts. One set of cousins found our grandfather’s name on a list and quietly collected all the money. This only came to light after my sister began researching whether there was any such account, with the intention that anything found would be divided among all the descendants.

That is but an unfortunate coda to this refugee story, though. The bigger picture is that our ancestors survived, through resilience and resourcefulness and some notable good luck: a benevolent SS officer, a misconstrued telegram, an undetected rug. My sister Denise, brother Mark and I are grateful that we’re here.

The extended family was far less fortunate. My grandmother’s seven siblings and their children lived in Poland, and all 37 of them were shot after the Nazi invasion. My grandfather’s sister, her husband and their son Erwin were deported from occupied Belgium and perished in the Auschwitz gas chambers. My uncle never forgot attending the opera in Vienna with Erwin, who was so sensitive that he covered his ears at the fake gunfire of an execution on stage.

—Kenneth Silber is author of In DeWitt’s Footsteps: Seeing History on the Erie Canal and is on Twitter: @kennethsilber