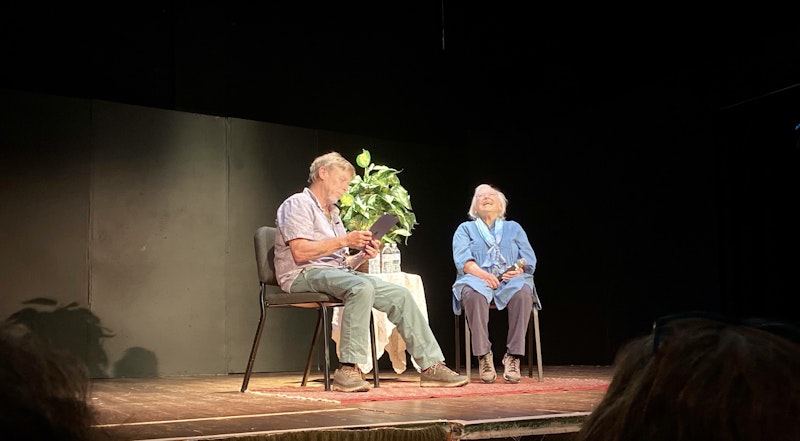

This is a text for No Ordinary Person, a program of autobiographical monologues (co-founded by my mother) performed at the theatre in Washington, Virginia (little Washington) June 16-18.

Early last winter, when my cousin Ellen (that's my step-father's sister's step-daughter; you know, my cousin) called, unexpectedly. I was at my office at Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in the last week of classes. She told me that my mother, 97-year-old Joyce Abell, still living independently in her house in deeply rural Rappahannock County, Virginia, was feeling poorly. By an hour later, Ellen's brother Howard had given Joyce a Covid test, which came back positive. Sallie and Tod Morgan took her to the doctor in Warrenton. There, she lost consciousness. She was taken by ambulance to the hospital.

The various strains of Covid were getting milder by then, but we'd lost a million people, most of them elderly. I wasn't certain my mother would be returning home. As I threw my stuff together, I included copies of her will and Power of Attorney. I spent the three-hour drive along Route 15—south through Gettysburg, Thurmont, Frederick, Leesburg in a cold rain—in pre-grieving, planning what I'd say at the memorial service, thinking about the 65-year arc of our relationship and about my mother's whole life.

Four hours or so after the call, I got to the waiting room at Fauquier hospital. Tod was there, tired but steady. "They're releasing her right now," he claimed. It seemed impossible. But a minute or two later, there they were, Sallie pushing Joyce in a wheelchair. Somehow, she was already able to find the chair intolerable, for she's a fierce walker, and kept saying she could make it on her own. I was annoyed by that, because it's the sort of thing I've heard a lot over the last few years and I think she needs more help. I was unbelievably relieved as well, to hear her talking at all, much less in that fierce Joycean vein.

We signed some forms and then wheeled out to the car. I hadn't been aware up until then that Warrenton had a rush hour, but the traffic was heavy and the rain kept pouring as clouds wrapped the mountains and the gray winter daylight wound down early. We sloshed past the Glock shop and the Child Care and Learning Center; and as we arrived at her house on Rock Mills Road, the complexities of our situation began to dawn on me. When she gasped or coughed that evening, I wondered whether she'd stop breathing. If she kept going, it seemed that, in a classic role reversal, I was going to be her long-term care person, a job for which, I thought, I had little competence and limited inclination. And though I was scheduled for a sabbatical, I still had a full-time job. But ready or not, I've been down here ever since, more or less, on sabbatical and now in retirement.

And despite the testimony of the medical authorities that "her vitals look good," Joyce was pretty sick in that weird Covid sort of way, like I was when I had it last summer. At times she breathed fine, at others she struggled. She's grown forgetful lately, but she was definitely showing the symptoms of “brain fog” for a couple of months. She spent a concerning amount of time asleep. But as we lived together in the months following that, she continued right back to the normal aging curve for nonagenarian her. “Resilient” might be the word.

•••

Ma's Covid wasn't the first time we'd been on the brink together. In 1971 I was 13, living in northwest DC with my brother Adam and mother. My father had recently declined further into alcoholism and was kicked out of the house, if I'm recalling correctly. On this particular sunny Spring morning, I didn't feel well. I didn't think I should have to go to school. This was always a hard sell with Mom, who wasn't into hearing her children's excuses. A real hard-ass. Also, sometimes I did pretend, or try to heat up the thermometer to fever pitch on the radiator. But she put the back of her hand to my forehead as opposed to reading the lies of mercury, and said "You're running a fever." So I stayed home and laid out on the couch all morning watching TV, also a rarely-permitted indulgence. When she called me for lunch I had the bizarre realization that I couldn't stand up. I was at 105, I think. Tiny fortyish Joyce somehow carried me down the stairs to the street and into her car and drove me to Doctor Coleman's office in Silver Spring. Then I was in Children's Hospital downtown, getting a spinal tap. Meningitis.

It's weird that I remember the whole thing, because I was delirious. I recall that I was embarrassed to be naked in front of the nurses because I’d just sprouted pubic hair a week or two before. It seemed an unfair time to get hospitalized. But everything about that day and night still seems vivid. All night I heard voices screaming and saw harpies swooping at me out of a fog. I didn't know whether I was awake or asleep, dreaming or delusional. I kept thinking the voices had to be real. Thrashing and sweating, I soaked the whole mattress, which I suspect they incinerated or something. But the fever "broke"; by the next morning I felt washed-out but okay. Everyone seemed surprised, but the look on my mother's face as she sat next to me that morning was something I hadn't seen before. I realize now that she’d braced herself to lose me or for my remaining life to be limited by illness or paralysis. She registered joy, relief, grief, all at once.

And maybe I didn't quite understand that look until I had it on my own face 50 years later, looking at her. Right then, in 1971, I made a resolution not to pre-decease my mother. That's been a longer, tougher job than either of us thought it would be.

•••

As a child in Chicago around 1930, Joyce almost died of... well, scarlet fever, diphtheria, or rheumatic fever (I recall her saying the first when I was little, the second in my adulthood, the third when I asked her about it this spring). In any case, it was an outbreak, and she remembers the mother of one of her friends just up the block in Ravinia, draping her child's window in black, and displaying a picture of the dead boy. Joyce emerged from her illness with a heart condition, and when her mother Hilda took her to a Group Health clinic a few years later, Joyce overheard the doctor saying that she was unlikely to make it to 20: that is, to 1945. She not only made it to victory in Europe day, but to defeat in Vietnam, and even to the indictment of Trump, which she was holding on for.

The other morning, Joyce said something she often says, in one version or another, at the breakfast table. "What is amazing to me is that I am alive today! I can't believe this! How the hell did I last this long? How did I get through things?" She says that on some days and hours the world seems gray and she’s just slogging through, but that on others, the awareness that she’s alive sneaks up and grabs her. "I can't believe I'm here!" she'll sometimes say, rather suddenly. "I love being alive! It's like the God I don't believe in pointed at me and said’ 'people will say she'll die young, but I'm not going to let that happen'." That's her atheist faith.

She often asks me things like this: "When you were young, did you ever think you'd be where you are now?" "I can't believe I ended up here in Rappahannock living on a farm. Can you believe it?" It is surprising that she ended up here. She comes from lines of Jewish writers and intellectuals. She grew up in New York and Chicago, went to college at Berkeley, settled in DC as an adult and was “teacher of the year” in the Montgomery County, Maryland public schools. An urbane sort of person. I can see why she's surprised not only to be alive but to be alive here, down on the farm.

I don't experience my life as having a shocking and unexpected outcome. I sort of hopped on to a narrative early, as a professor and writer and husband and dad and pressed forward. Many things have happened that I didn’t specifically expect: many people and jobs and homes and projects and problems. But I don’t look back at my whole life as a series of improbable events culminating in an improbable old age that I never anticipated. It seems like a fairly predictable grind to me. I should’ve let the meningitis or many other things teach me a pure joy at the simple fact of being alive; instead I sort of forgot about it and went right back to adolescence. After that, I had daily headaches for decades, rather than an irrepressible love of life.

The opposite of living in anticipatory grief, or in a routine grind, is waking up each morning surprised by the day as though it's a gift, not something you braced yourself for at all, but an unexpected joy that overtakes you. I know in many ways my mother is still braced for bad things to happen; in fact she thinks the world is going to hell and that we might not make it another 20 years. Well, she might not make it another 20 years. I might not either, though I've resolved to outlast her if it kills me. But she might make it to tomorrow morning. We all might. If we do, we should greet the day with exultation. But for Joyce, it's not a matter of “should”: the exultation sneaks up on her and surprises her afresh, every time.

It might occur to you or to me, as we edge toward or through it, to wonder whether old age is a good thing, an intrinsically worthwhile period of life, or rather a slow and relatively pointless decline into death: a time of waiting or a sort of limbo, if it’s not of pain and disintegration. But in her late-90s, intermittently, my mother has discovered and is enjoying a kind of happiness that perhaps she was incapable of earlier in her life. I don't really know, of course! And I haven't known her for her whole life. She says I'm wrong about this. But she had a difficult childhood and early adulthood, and she carved chances of happiness out from that difficult life. In the course of the 20th century, she experienced the happiness of human connections, of jobs well done, and homes well made. But I think she also experienced a continual sense of dissatisfaction. There always had to be more to push toward, more to create, more to understand, or things that weren't satisfactory: a rhythm of need, struggle, understanding, provisional resolution. Now, she's reached a different moment, at which the point is not what she can use her life to accomplish, but whether she can experience her right-now-aliveness fully. She can, as it turns out. It makes me want to grow old too, even with all the drawbacks. I'll outlive her if it kills me, I said. But if I take after her, living to an immense age might bring me back again and again to life.

Sometimes I wake up thinking, as I have woken up thinking on and off for the last 10 years or so: this round of eating, excreting, bathing, sleeping is so repetitive. Do I have to do all this again today? I've lost the sense of purpose, the oomph, the momentum. The day seems a gray slog. But then I come downstairs as my mother struggles to make herself a cup of tea, and we sit down to breakfast. Visibly, she experiences the very opposite of anticipatory loss, the grief preview that I'm still running in my head about her. Her face takes on a refreshed vivacity, her voice a fresh intensity. "I never thought I'd still be here!," she says. "Can you believe it?" Well, no, Ma, I really can't believe it.

—Follow Crispin Sartwell on Twitter: @CrispinSartwell