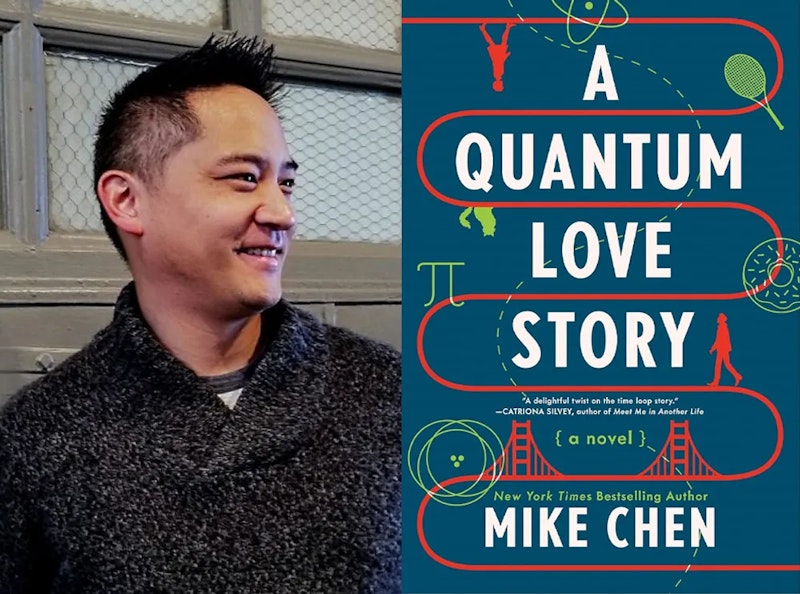

A Quantum Love Story, by Mike Chen, an entertaining novel about two people stuck in a time loop, inspired me to contemplate recurrent events, fading memories and long-ago connections. In the story, the Hawke Accelerator, “both a modern marvel of technology circa 2094 and also some sort of weird top-secret project that no one really understood,” explodes and resets the timeline to a few days before the explosion, again and again. Carter Cho, an accelerator technician and failed quantum physicist, is at first the only person who realizes the recurrence, but manages to convince Mariana Pineda, a neuroscientist who’s touring the facility with a delegation from ReLive, a biotech company that makes a product that enables vivid memories (and which Mariana has illicitly taken, to aid her mourning of Shay, friend-turned-stepsister, who disappeared on a wilderness trip and has been officially declared dead).

Carter and Mariana undertake repeated efforts to figure out the factors underlying the explosion, along with anomalies that develop, such as a live mammoth showing up in a park near the accelerator. A romance kindles between the two, but the loops erode his memories of who she is, requiring Mariana to undertake world-saving efforts increasingly alone. It emerges that a solution to the cycle may involve time travel a couple of decades back so as to fix a construction error in the accelerator; but appearing in the past—in a world where you don’t belong, one with a younger version of yourself—raises dangers of temporal paradoxes that could have dire consequences unpredictable even by Bowie, an AI patterned after a long-ago rock star, and a valuable interlocutor if one has to undertake extended self-isolation.

Before I finished Chen’s novel, I read an op-ed by Francis Fukuyama lamenting the state of American politics, including that “an astonishing number of Americans have bought into bizarre conspiracy theories and alternative realities,” an assessment in line with my own. I remembered that I interviewed Fukuyama twice, decades ago. The first time, in 1995, was for the conservative magazine Insight on the News, to discuss Fukuyama’s book Trust, which argued that societies with high levels of trust (the U.S. was one, he thought then; I presume he no longer does) have a big advantage over low-trust societies (he considered China an example, arguing it wouldn’t be as important as widely thought, an evaluation he may or may not still hold). I’d read Trust dutifully, but somehow gave Fukuyama the impression I hadn’t, as he said something like “When you read the book.” Disconcerted, I didn’t correct him.

I interviewed Fukuyama again in 2002, for Book, a magazine backed by Barnes & Noble; I’d almost entirely forgotten this interview or that there was such a magazine. (Like Insight on the News, Book is long gone, and my writings for either are hard or impossible to access online.) This time, the subject was Fukuyama’s book Our Posthuman Future, which warned about dangers of human genetic engineering. Fukuyama had become famous for his argument that the Cold War’s conclusion marked an “End of History,” in which ideological conflict would diminish. He didn’t believe that Al Qaeda’s 9/11 attack changed that picture, as its ideology, he thought, had no future. But he worried biotech could restart “History,” by creating genetically distinct populations that would view each other with fear. That strikes me as plausible, given America’s current divisions even without genetic engineering.

The 2024 election has a time-loop quality, not just in the expected repetition of the 2020 nominees, but in the sense that laws and norms are breaking down, much as if an out-of-control particle accelerator were ripping the fabric of time and allowing absurd anomalies to take hold, whether that’s a mammoth on the National Mall or the possibility that Donald Trump will become president again after trying to steal the last presidential election through transparently-false claims of fraud and recorded-on-tape efforts to corrupt public officials to “find” phony votes and not count real ones. Memories of these crimes shouldn’t fade. In A Quantum Love Story, getting thrust into the past has a sickening quality, like “little bits of electricity that tickle you and smash your skull in.” To me, Trumpism is no less repulsive.

—Follow Kenneth Silber on Threads: @kennethsilber