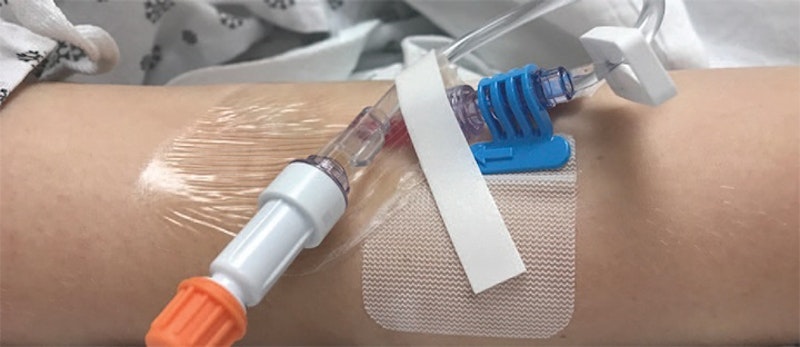

Once, in my early-20s, while working on a small construction site, I stepped on a nail. It went through the ball of my foot, stopping just before exiting. The four-inch nail had been driven through a small, two-by-one inch square piece of wood which was meant to serve as shimmy to level out a drywall ceiling we were putting up. There was a box full of them, and one made its way to the cluttered work floor so I didn’t see it. It didn’t hurt that much. I looked at it with clinical distance, braced myself, and then pulled it out. I was surprised that it didn’t bleed very much. I didn’t do anything but wash the wound. That night my foot began to swell up and by nine was about twice its normal size. I went to the emergency room. They looked at it with what I felt was unreasonable alarm—it didn’t hurt—and I was immediately admitted.. Within half an hour I was in a bed with inter-veinous transfusion drips, a host of antibiotics, and a staff of doctors and nurses seeing to my recovery.

I’d never stayed in a hospital before and enjoyed it. It was a “leave the driving to us” situation; a patient is a passive creature. It felt a bit like a vacation. I had a private room. I didn’t have to finish the drywall ceiling, the doctors and nurses were friendly, I was waited on constantly, friends and family visited, bringing me books, sympathy and conversation. The days passed pleasantly. I read, ate, occasionally watched the TV news and anticipated the regular visits from the nurses and doctors.

After a week I finally asked one of the doctors why I was still in the hospital. I told him I felt fine and didn’t understand why I hadn’t been discharged. He said that I wasn’t responding well to the antibiotics and was under surveillance. He added that if the infection started spreading up my leg, there was a danger of amputation. Then he left the room.

My feelings about the hospital stay changed immediately. I was lulled by comfort and the abandonment of personal responsibility while not realizing the seriousness of the situation. Constructing a drywall ceiling was nothing in comparison to what I imagined as my possible Ahab-like future. I thought about the smiling doctors and nurses and everything turned upside-down. I had two thoughts, “Get better and get out!” Happily, a week later I walked out on my own two feet. This led to my conviction that the relation between our minds and the health of our bodies is directly linked.

Sickness can be comforting. I know a few people who make a virtue out of illness. These illnesses may be physical or mental. There must be something called “Patient Syndrome” where a person gets used to being cared for, coddled, looked after.

This is the subject of Thomas Mann’s book The Magic Mountain. Its hero, Hans Castorp, a bland upper-bourgeois German, visits his cousin in a tuberculosis sanatorium high in the Swiss Alps. Though he goes with the intention of staying three weeks, he remains for seven years. He gets caught up in the atmosphere, he’s distracted, there’s the feeling of being part of a select society of the “tainted” as he calls them, he’s comfortable and surrenders up his personal will. His state of suspended animation continues until, at the end of the book, World War I breaks out and he finds himself on the battlefield running over corpses in the mud.

People want to feel good about themselves, comfortable and at ease. One learns in physics class that any given system seeks the level of the lowest possible tension: entropy. Could there be emotional entropy? If so, it would consist of the renunciation of personal responsibility and the desire not to look directly at facts. It’d be the moral equivalent of aligning oneself with lies and moral sickness. This is how I felt laying in the hospital for that first week.

Comfort’s attained only through falsity, self-willed blindness and, above all, hypocrisy. Westerners live in a diseased world where cities are becoming unhabitable, people increasingly unhealthy, poorly-educated, violence is excused, filth is everywhere, personal responsibility is minimalized, and there’s little social cohesion. But for the sake of comfort, we’ve decided not to notice.