Yukio Mishima wrote near the end that his life was divided into four rivers: writing, theater, body, and action. He memorialized as much as possible of it through photographs. Some were conventional. When he came to New York with his wife for a belated honeymoon in 1960, they were photographed on the Staten Island ferry, like any tourists. A few years later, the elegantly dressed, smiling man of letters posed for news photographers before the Manhattan skyline.

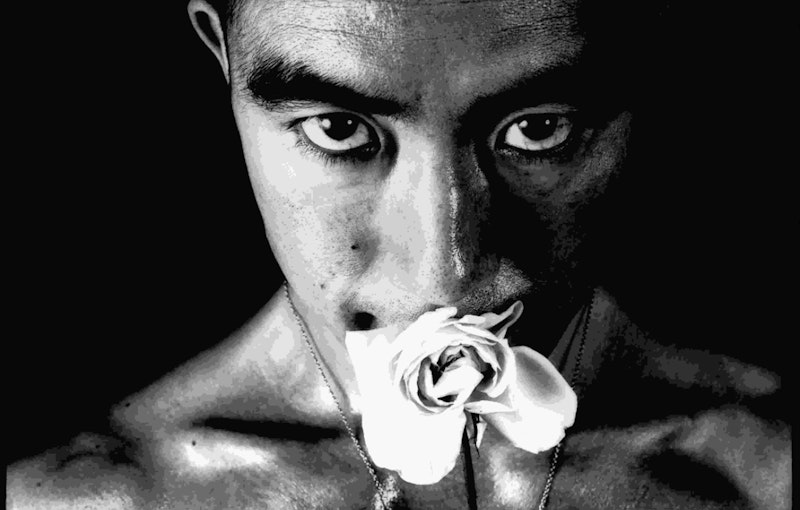

A body-builder for the last two decades of his life, his love of self-display crossed into exhibitionism. Thus, the beautiful, homoerotic photographs: Mishima in a fundoshi, a loincloth, kneeling in new-fallen snow with a dai katana, the great sword of a samurai, or posing as Guido Reni’s St. Sebastian (complete with arrows). He even posed for Barakei (roughly, Death by Roses), a magnificently produced luxury book of extraordinary nude photographs. Surprisingly, he was disturbed by the consequent letters received from various admirers requesting still bolder portraits. After all, he was a family man.

Perhaps the four rivers joined in his most famous photograph: Mishima, stripped to the waist, his chest bulging with muscle and gleaming with sweat, his brows knotted and eyes glaring, wielding a massive, two-handed, three-foot-long dai katana. This was an elegant weapon, made by the legendary 17th-century swordsmith Seki no Magoruku, and kept razor sharp. About his head is a hachimaki, a white headband bearing the Rising Sun and a medieval samurai slogan, “Serve the Nation for Seven Lives,” a paraphrase of the 14th-century samurai Kusunoki Masashige’s response to the question of how he would like to reincarnated in his next life: “As a man, as a man for each of seven lives, and in each of them to serve the Emperor unto death.”

Yukio Mishima first came to New York in 1951 when he was 26. Within the previous two years, he had published two outstanding novels, Confessions of a Mask and Forbidden Colors. The critics hailed him as a genius. He spent 10 days in the city, going to the top of the Empire State Building, seeing the Radio City Music Hall and the Museum of Modern Art, and catching Call Me Madam and South Pacific. New York didn’t appeal to him: he found it “like Tokyo five hundred years from now.”

Mishima was born Kimitake Hiraoka, the eldest son of a middle class family. Before he was two months old, his paternal grandmother took him from his parents and kept him until he was 12. Her ancestors had been samurai, related by marriage to the Tokugawa, the Shoguns. She was chronically ill and unstable. Yet she loved theater and took him to the great classics, such as The 47 Ronin, perhaps the most stirring Kabuki play, a magnificent celebration of loyalty and honor even unto death.

Through her family connections, he entered the elite Peers’ School. By 14, he was publishing in serious literary magazines. He took the pen name Yukio Mishima to escape parental persecution for his father, as a Confucian, considered fiction mendacity and destroyed his son's manuscripts whenever possible.

In 1944, he graduated as valedictorian. He received a silver watch from the hands of the Emperor. His luck held: he failed an Army induction physical. Thus, he survived the Second World War.

From the beginning, Mishima’s productivity was stunning. In 1947, he published 13 stories, a first novel, a collection of novellas, two short plays, and two critical essays. On November 25, 1947, after retiring from a career of nine months at the Finance Ministry, he began his first major novel, Confessions of a Mask. Mishima brilliantly evokes his closeted protagonist’s awareness of being different and sense of unique shame. Within two years, Mishima revisited this theme in Forbidden Colors, now noting homosexuality’s ubiquity. He closely observed gay life, writing of it with a candor and sensitivity then matched in the West only by Gore Vidal’s contemporaneous novel The City and the Pillar.

Besides, he wrote in a society that responded to homosexuality far differently from the West. During the last two centuries before Japan reopened to the West, some of its most flamboyant heroes were bisexual picaros whose panache and courage on the battlefield were equaled by delicacy and endurance in a diversity of intimate situations.

In July 1957, after Alfred A. Knopf published his Five Modern Noh Plays, Mishima returned to New York on a publicity tour. He thought Knopf, who affected clothing in an orgy of clashing colors, “dressed like the King on a whiskey bottle.” He was interviewed by The New York Times, saw Christopher Isherwood, Tennessee Williams, and their friends, saw eight Broadway shows, and went several times to the City Ballet.

He returned to Japan to find a wife. This wasn’t as easy as one might think. Marriages were and still are often arranged. He was one of Japan’s most distinguished men of letters. But Mishima’s affect was apparently unattractive. A weekly magazine had polled Japan’s young women on the question, “If the Crown Prince and Yukio Mishima were the only men remaining on earth, which would you marry?” Half the respondents preferred suicide.

Nevertheless, his marriage to Yoko Sugiyama proved successful. They stopped in New York on their belated honeymoon, where he saw two of his “modern Noh plays” performed in English at the Theatre de Lys. They had two children: he proved an attentive, devoted father.

They lived in a house he had ordered built in a style some called Victorian Colonial, perhaps because the English language lacks words to better describe it. John Nathan wrote, “For Mishima, the essence of the West was late baroque, clashing colors, garishness… As he explained to his horrified architect, ‘I want to sit on rococo furniture wearing Levis and an aloha shirt, drinking Coca-Cola; that’s my ideal of a lifestyle'.”

From 1965 to 1970, he worked on his four-volume epic, The Sea of Fertility (Spring Snow, Runaway Horses, The Temple of Dawn, and The Decay of the Angel). “The title,” he said, “is intended to suggest the arid sea of the moon that belies its name.” It’s his masterpiece: he knew it would be.

At a first glance, in taking the theme of the transformation of Japanese society over the past 150 years, Mishima is revisiting the tired, even trite conflict between traditional values and the spiritual sterility of modern life. One might better define the epic as a lyric expression of longing, which he apparently believed the central force in life. To Mishima, longing led one to beauty, whose essence is ecstasy, which results in death. His fascination with death is erotic: he was drawn to it as most of us are drawn to the company and the touch of the beloved.

In his essay "Sun and Steel," he wrote of “a single, healthy apple… at the heart of the apple, shut up within the flesh of the fruit, lurks the core in its wan darkness, tremblingly anxious to find some way to reassure itself that it is a perfect apple. The apple certainly exists, but to the core this existence as yet seems inadequate... Indeed, for the core, the only sure mode of existence is to exist and to see at the same time. There is only one method of solving this contradiction. It is for a knife to be plunged deep into the apple so that it is split open and the core is exposed to the light… Yet then the existence of the cut apple falls to pieces; the core of the apple sacrifices existence for the sake of seeing.”

Mishima stood about 5’2”. He glowed with charisma and an undeniable, disturbing sexuality. Every memoir testifies to his extraordinary energy. He was brilliant, witty, and playful. He had self-knowledge and a keen irony, and his own absurdities were often their target.

Both Japanese and Westerners testified to his extraordinary empathy: his ability to understand and respond to others. Thus his genius for conversation: the man who loved discussing the Japanese classics, Oscar Wilde, or the dozen shades of red differentiated in the Chinese spectrum could also discuss weightlifting or kendo or a thousand other subjects, each gauged to his listener. He could make his companion feel that he or she was the most important person in the world to him. It was a useful gift for a man who understood that he lived behind many masks, or in a series of compartments, and that no one knew him whole.

From the mid-1960s, he became politically active on the extreme right. Eventually, he organized an elegantly uniformed 50-man private army, the Shield Society.

On November 25, 1970, 23 years to the day from beginning Confessions of a Mask, Yukio Mishima was 45. He had published 30 novels, 18 plays, 20 volumes of verse, and 20 volumes of essays; he was an actor and director, a swordsman and body-builder, a husband and father. He spoke three languages fluently; he had gone around the world seven times, modeled in the nude, flown in a fighter jet, and conducted a symphony orchestra. During the evening before, he told his mother that he’d done nothing in his life that he’d wanted to do.

On November 25, he led a party of four members of the Shield Society to a meeting with the commanding general of the Eastern Army of the Japanese Defense Force. He had finished revising the manuscript of The Decay of the Angel only that day: it was on a table in the front hall of his house, ready for his publisher’s messenger.

At army headquarters, armed only with swords and daggers, Mishima and his men took the general hostage. They demanded that the troops be assembled outside the building to hear Mishima speak.

A little before noon, with a thousand soldiers milling about, Mishima leapt to the parapet of the building. He was dressed in the Shield Society’s uniform. About his head was the hachimaki.

He began speaking, but the police and television helicopters drowned out many of his words. He spoke of the national honor; condemned the rich, the greedy, and the powerful; and demanded the army join him in restoring the nation’s spiritual foundations by returning the Emperor to supreme power.

He had once said, “I come out on stage determined to make the audience weep and instead they burst out laughing.” It held true now: the soldiers shouted that he was a bakayaro, an asshole. After a few minutes, he gave up. He cried out three times, “Heiko Tenno Banzai”—“Long Live the Emperor”—and stepped back.

He loved Josho Yamamoto’s classic Hagakure, an 18th-century work of moral guidance for the warrior. Its opening line is “The way of the samurai is to be found in death.” The Hagakure argues that shinjo, a true heart, is achievable only by facing up to one’s mortality and detaching oneself from fear of death, to die before you die. Having done this, the threat of death has no power to coerce behavior. Only then can one act purely, by principles of justice and righteousness.

Mishima had fantasized about kirigini—to go down fighting against overwhelming odds, sword in hand. That wouldn’t happen now. He kicked off his boots and stripped to his fundoshi. He sat on the carpet. Mishima took a yorodoishi, a foot-long, straight dagger, in his right hand. He took a deep breath. Then his shoulders hunched as he drove the blade into his abdomen with great force. As his body attempted to force out the weapon, he grasped his right hand with his left and continued cutting. The blood soaked the fundoshi. The agony must have been unimaginable. Yet, he completed the cut. His head collapsed to the carpet as his entrails spilled from his body.

He had instructed Morita, his most trusted follower, “Do not leave me in agony too long.”

Now, Morita struck down with Mishima’s dai katana. He was inept: the beheading required three strokes.

Then Morita took his own life.

Mishima’s motives remain the subject of speculation: madness, burnout, or fatal illness. Some whispered he might have enjoyed the pain. Others suggested he and Morita had committed shinju, a double love-suicide. Some argued aesthetics. A reading of "Sun and Steel" indicates suicide was the logical completion of his search for beauty.

Others take him seriously. Japanese culture long accepted this agonizing form of suicide as funshi, the most sincere protest one could muster against wrong by backing up one’s words with one’s life. It was a matter of honor.

Every year, thousands observe the anniversary of his death.