The inscription from Anne Rice to me in her 2006 book Christ the Lord: Out of Egypt reads as follows: “Mark, This comes with my thanks for you truly wonderful writing, for the authors you’ve recommended, and with my love for you as my fellow writer and believer. Mark, I love you! May you enjoy every blessing! Anne aka Anne Rice 2006.”

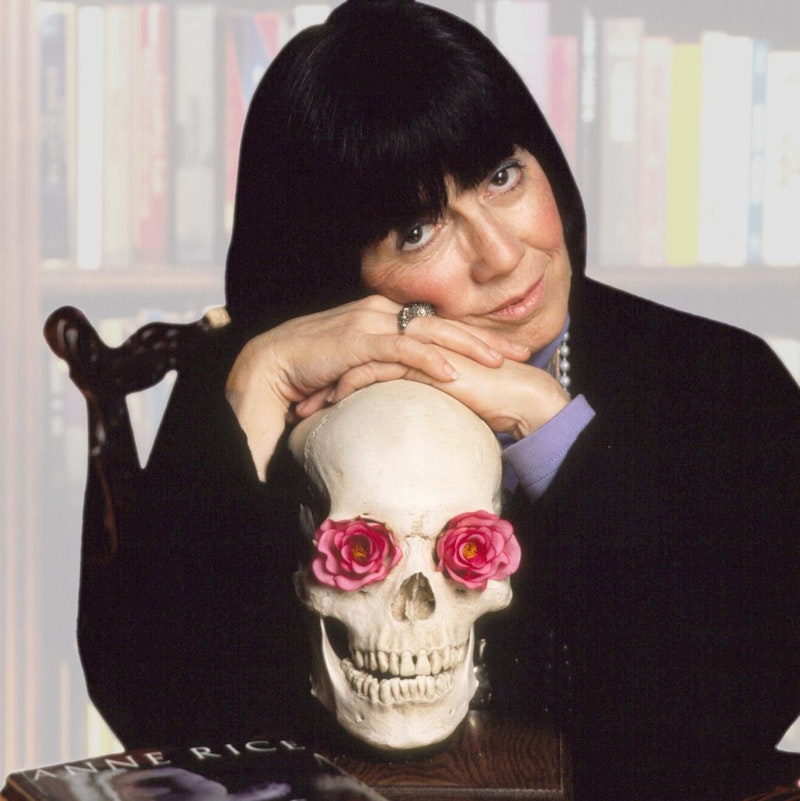

It’s a lovely message, and a reminder to me of the period, roughly 2005-2009, when I was friends with Rice, the famous author of The Vampire Chronicles.

Catholicism brought Anne Rice and me together. Rice had announced a return to the Church in 1998, an unexpected piece of news that shook the media—the vampire queen herself had turned towards Rome. I too had come Back to Catholicism. In 2005, around the time Rice published Christ the Lord, I published a book called God and Man at Georgetown Prep. We were both members of the One True Faith.

Rice and I became personally connected, through mutual friends in the faith. I’d read her first novel Interview with the Vampire at my brother’s suggestion in 1980, and like everyone else immediately recognized it as not an exercise in genre horror but a beautiful philosophical work. I’d been a fan for years.

Now it was 2005 and I was friends with the author. We emailed every day and she invited me to visit her in California—a trip I didn’t make due to illness. That illness is when I experienced Rice’s true Christian kindness, which you never really heard about much in public.

Before my illness happened, however, there were the emails and the brief phone conversations (although I recall she hated getting on the phone). We recommended Catholic authors, reminisced about the incense, holy water, candles, priests and nuns of the old-school Church. We talked about the plans to make a movie out of Christ the Lord, the book she’d written about Jesus as a young boy. I sent her a video of the Housemartins’ song “Caravan of Love” and she flipped over it, buying everything the band ever did. Anne Rice and the Housemartins is an incongruous pairing, but it’s true.

When things were at their most intense (at least on my end), my girlfriend caught me at dinner—and even in bed—gushing about Anne. “Oh my God,” she said. “You’re in love with Anne Rice.”

One of the reasons I think Rice and I hit it off so well is that we were Catholics who also had, as Carl Jung put it, integrated our shadows. Rice had written books under a different name that were highly sexual. In her 1986 novel The Vampire Lestat, she made the vampire a rock star. At the time the book came out I was working in a record store and living the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle. Lestat’s passion and nocturnal hunts were like clubbing. Anne and I weren’t the kind of Catholics who got invited to speak at Mass.

It was during the planning stages of that Christ the Lord film that trouble started. Because Rice was so famous and wealthy, I knew that the grifters of Official Christianity would storm her like the Irish at an open bar. She got in with a guy named David Kirkpatrick, a former bigtime Hollywood executive. Kirkpatrick announced plans to construct a massively expensive new faith-based film studio in Massachusetts. He had his hooks into Anne, but the grift collapsed when it was revealed that he had no money backing his talk. Rice, furious, cut off all ties with Kirkpatrick—and shortly after renounced organized Christianity; it wasn’t just the grifters but the fact that Anne was very liberal. Leftism is also a religion and it was bound to clash with the Church.

Anne soon stopped corresponding with me. Yet her final act of kindness towards me still makes me a fan—and believe that right now she’s resting in the arms of the Lord. In 2007 I started not feeling well. One autumn afternoon I emailed Anne about that, but was going to take the dog for a long walk through the lovely fall woods in Maryland. ”I am with you on the walk,” she replied.

Shortly after, I wound up in the hospital. It was cancer. I told Anne. I went to my local priest to get the sacramental Anointing of the Sick. The priest had me raise my arms up like Jesus, then began praying over me and administering holy oil, I felt an electricity pulse charge through me. I returned home and confidentially announced to my family that while I’d die someday, it wouldn’t be now and it wouldn’t be from this. God had told me. Also, Anne Rice was praying for me. They thought I was goofy.

The next day, a FedEx truck pulled up in front of my house. It was a brand new computer from Anne—along with a check for $10,000.

Rice would leave organized religion in 2009, although she still called herself a follower of Christ. She left with a bang: “For those who care,” she wrote, “and I understand if you don't: Today I quit being a Christian. I'm out. I remain committed to Christ as always but not to being 'Christian' or to being part of Christianity. It's simply impossible for me to 'belong' to this quarrelsome, hostile, disputatious, and deservedly infamous group. For ten years, I've tried. I've failed. I'm an outsider. My conscience will allow nothing else."

A lot of Official Christians said told-you-so, that Rice was at heart a liberal and eccentric who wrote about the occult. Yet seeing Anne’s words to me in my book and thinking about the incredible generosity she showed to me, I know she was probably one of the most Christian people I’ve ever known. Her final, vituperative rejection of the craziness and grift that can be part of high-profile Christianity reminded me of Jesus bouncing the money changers out of the temple.