Teenagers who discover J.D. Salinger's 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye, usually do so around age 15, when they often share the confusion and despair experienced by the story's anti-hero/narrator, Holden Caulfield, a 17-year-old angry young man who's just been expelled from "Pency Prep" in Pennsylvania for bad grades. This book's often a gift from a parent hoping to assure their child that they're not alone in their adolescent struggles, or it's assigned by an English teacher. The fact that the novel's frequently been banned in high schools has added to its allure among young people. The fact that Mark David Chapman was found with a copy of it on the night that he murdered John Lennon muddies its mystique.

I've read countless novels, but none ever mesmerized me like that one. I read it in one sitting, which kept me awake until four a.m. on a weeknight. Everything about the sullen, anti-establishment protagonist fascinated me, in particular his proximity to New York and the ability that gave him to walk the city's streets at all hours by himself. By contrast, I could walk down my hometown's main street in under 10 minutes, and that was about all there was to see there.

Salinger's novel was the first book I'd read that had a narrator close to my own age, which made it feel like he was talking directly to me in an anxiety-driven stream of consciousness aimed at achieving some sort of catharsis. That gave the story an immediacy that an adult novelist trying to convey the teenage experience using a third-person narrative voice would’ve had a hard time replicating.

For the past several years, I've been re-reading some novels I enjoyed years ago, which is why I just read this one again. The results of this endeavor have been mixed. Hemingway, for example, disappointed me the second time around. I found his prose, except for selected passages, repetitive and monotonous in both The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms. And while I've long been a major fan of James Ellroy, rereading L.A. Confidential a couple of months ago was an aggravating experience due a labyrinthine plot that I found exhausting.

One of the lines that stands out in The Catcher in the Rye is when Holden says, "What really knocks me out is a book that, when you're all done reading it, you wish the author that wrote it was a terrific friend of yours and you could call him up on the phone whenever you felt like it. That doesn't happen much, though." That definitely didn't happen with L.A. Confidential.

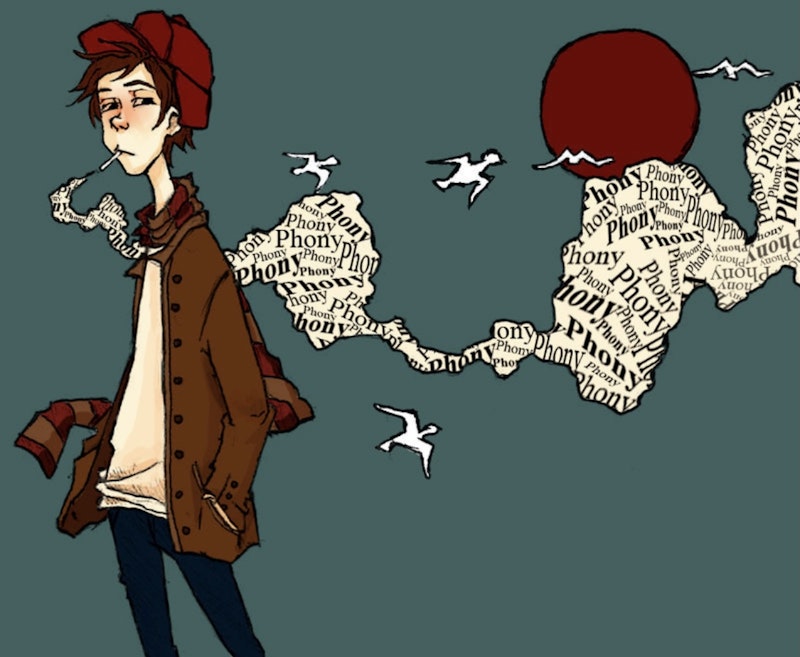

Given the impact it once had on me, re-reading Salinger's novel set me up for automatic disappointment. But that's okay, as you only get to experience some adolescent thrills once. In the revisionism, a common complaint has been that Holden Caulfield whines too much. I didn't notice that at 15, but I did this time around. I wanted him to do something, instead of using his obsession with "phonies" as an excuse to do nothing.

Readers have long revered Caulfield as a rebel, but he doesn't rebel very much. The sulky teen didn't get kicked out of yet another prep school because he stood up to some "phony" teacher, but rather because he was too lazy to pick up a book. Compare Holden to another teenage literary hero who was searching for a path to adulthood—Huck Finn—and he pales in comparison. Finn made the moral journey from initially believing that it was wrong to help a slave—his black friend, Jim—escape to freedom to feeling an obligation to help effect Jim's freedom. By contrast, the most altruistic thing Holden does is write an essay for his lady-killer roommate so the guy can go on a date. Holden's not a bad guy; he just doesn't do much of anything.

I don't mean to give the impression that re-reading The Catcher in the Rye was a mistake. The book's many naysayers love to point out that Holden is totally unlikeable, but I disagree, even though I don't need to be enamored with a novel's main character to appreciate him. Holden's got enough spunk as a teenager to wander around the streets of New York for days while experiencing the city's seedier side. There's something to be said for a kid with such an independent spirit, especially given the fact that today's teens are more prone to pile up activities to pad their college applications.

Caulfield remains a fascinating study in paradoxes. He hates phonies, yet admits to being one himself; he's both cynical and overly sentimental, especially in how he idealizes children, a subset of the human race capable of great cruelty. Some critics say that Caulfield is bereft of insights, but they're wrong. He shows his powers of perception early on in the book when he captures the personalities of both his suave roommate and his dorky next-door neighbor in the dorm. Holden can also be funny as hell, a trait that makes the pervasive sadness of his story more palatable.

While I'm glad I re-read The Catcher in the Rye, I wonder if J.D. Salinger is overrated. This is his only novel. He wrote three novellas and some fine short stories, but the output is scant for a writer with his heavyweight reputation. His novel's success turned out to be a pyrrhic victory, in that its acclaim pushed him down the path to becoming a recluse. Salinger became a writer who never stopped writing, but rarely published. He was like a golfer suffering from the "yips." This enhanced his myth, but the author didn't produce enough work to be up there with the likes of Mark Twain, Saul Bellow, and—more recently—Cormac McCarthy.

Publishing The Catcher in the Rye ruined Salinger as a writer, but perhaps the seed of his destruction was planted years before from his traumatic experiences as a soldier in WWII, which left him contemplating suicide. Writing this novel, which he labored over for years, might’ve temporarily kept the author's struggles at bay, but afterwards it seems that they returned and brought him down.