The one who’d attain the full light of consciousness (so as to perceive his person in all clarity without losing a sense of self) doesn’t generally go through life keeping the particular “compulsion at the ready”—namely, the one of always having an eye to record and polish a narrative solely in order that he may “feel his jollies,” or stoke his own ego. While in some situations, in the interest of survival, or, at least in wanting to live as trouble-free a life as possible, one must practice maintaining a hard countenance, or “play the tough guy,” though some people might be thought too dumb to be as calculatedly clever as they come off.

I had a college art instructor tell me that there was a “spiritual gas” which inflated the Buddha, and that this was why the enlightened one looked rotund in artwork. At roughly the same time I overheard a malicious young lady telling her unofficial boyfriend to not expend his gas—that it was “precious energy that you could use!” Ostensibly she was being helpful to the excessively introspective young man, though it’s doubtful this was really the case, as it seemed to serve primarily of amusing her peers. With the fusion of these memories I entered into my first job as an electrician: construction culture is a place where you can be insulted without knowing it happened, a place where, if one had ears to hear, esoteric truths are more palpable and plentiful in the passing than in the main fare of the most costly college offering, and a place where calculation and impulsiveness coexist and interweave in the most intricate ways, and at times in the most fecund spirit of spontaneity.

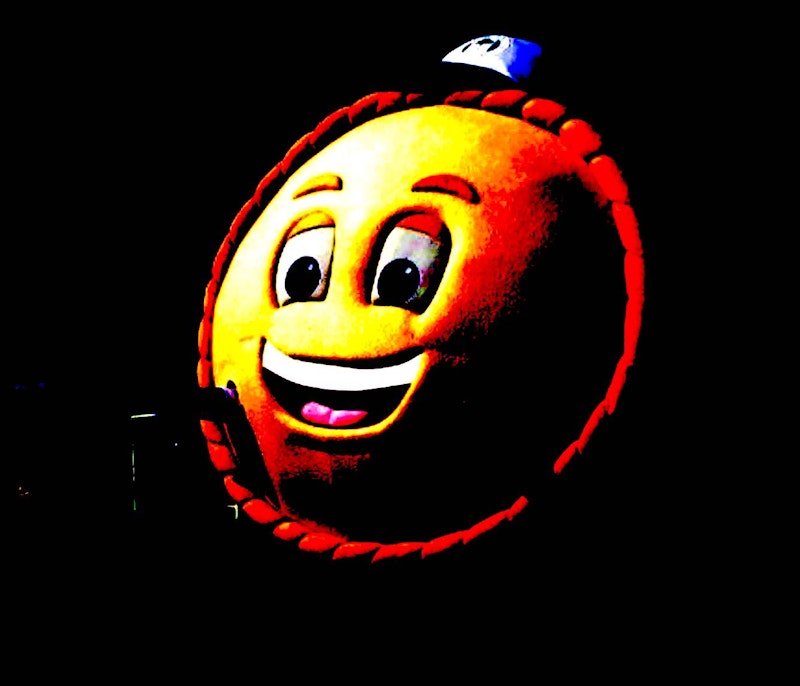

One day on the job I found myself in tight confines, completing the wiring of a high-voltage apparatus, and I ended up having to share this cramped workspace with a man who had the nickname “Pie.” There was a point when Pie had to traverse the space immediately beneath my back nether region as I was standing there, and not lacking circumspection, he plucked up the fortitude to do what had to be done, but with a reasonable request:

“Doan shit on meh,” he said.

“Aw, Pie, I wouldn’t shit on you.”

“Well, alright then,” he responded as he began his trek.

“…not on purpose anyway.”

Pie lit up, shouting, “Like I said, Doan shit on meh!”

I was older than him, and knew he was a reasonable guy, despite the zeal that’s common to youth. After a few silent looks with furrowed brows and some chuckling, he knew I wasn’t as virulent or plotting as all that. It was the scene of the forging of a special trust, because “having one at the ready,” in the chamber, was for most of the other guys in the shop the common state of being, regardless of whether he happened to be cretinous or malicious in disposition or inclination; and on the construction site either of these propensities was allowed opportunity for free expression during the day’s tasks, much more so than was the case in academia. The Buddha would’ve taught that it alleviated suffering, and helped the day pass after all.

Pie was a slice above his colleagues in this respect—a fellow who was really in the moment, though he paid no mind to mindfulness. It was this quality which enabled him one particular day to run up to the paramedic’s office, and to great comic/ghastly effect, extend his arm which had his hand at a lateral right angle to it, seemingly at a joint which just shouldn’t have been there, saying with an exaggerated dumb-guy voice, “Hey, duz thith look broken?” Wide-eyed, the ambulance driver said, “C’mon, we’re going!” before tearing out of the parking lot for the hospital. Just previously, Pie tried to catch a 400-pound spool of wire as it fell off the shelf, with one hand, and close to the concrete floor. The pace of Pie’s moment-to-moment consideration was a wellspring of material for introspection.

Good can come from mindfulness, fad though it may be. There was no teaching Pie. And yet it may be said with equal veracity of him, as it may be said of many a master: that he was and wasn’t mindful.