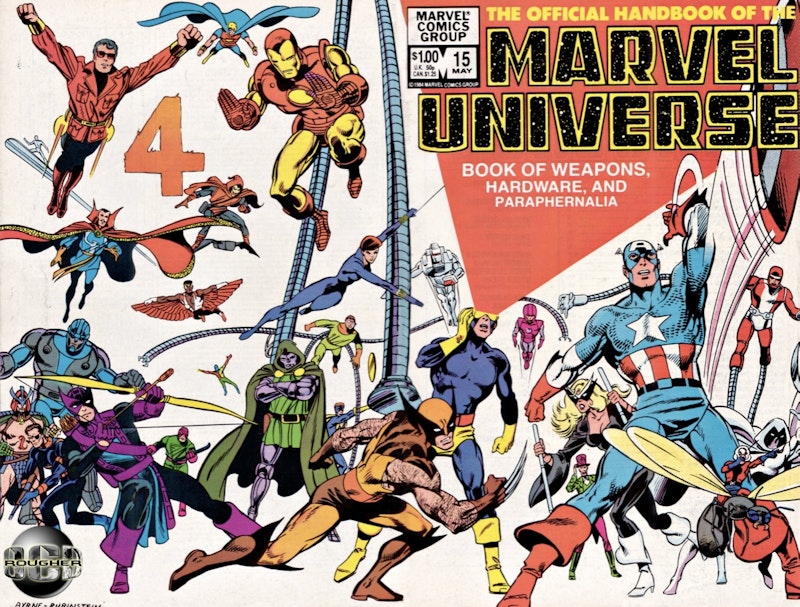

The Official Handbook of the Marvel Universe was a magnificent tool for learning the chronology behind your favorite Marvel characters. Aside from that, it also enabled comic book fans to arm themselves with just enough analytical data to believe they could accurately predict the outcome of virtually any potential altercation between comic book characters, and under nearly any imaginable set of circumstances.

To the writing team, this may also have had a stifling influence, as the granular detail with which the late Marvel Comics executive editor Mark Gruenwald defined each character’s strengths, weaknesses and abilities had the potential to smother creativity with respect to just how much power, explosiveness, brilliance, innovation or precision our favorite enhanced beings were capable of showcasing from one moment to the next.

From my own perspective as a comic book fan, this could be quite vexing at times for many reasons. The fitness enthusiast in me would become irate when characters touted as representations of real human beings exhibited feats of strength that were unintentionally, yet still categorically, superhuman. When all 6’2” and 240 pounds of Captain America is effortlessly bench pressing weights more than 300 pounds heavier than professional (and likely steroidal) powerlifters weighing 450 pounds have even approached, there’s no other descriptive word to assign to the feat other than “superhuman.” Similarly, when characters in the most popular books—like Cyclops of the X-Men—went from slightly above average physical combatants to masters of multiple martial arts with alarming and all-too-convenient speed, it seemed to be a gross violation of the very rules that Marvel had informed us they were playing by.

Then again, if I was frustrated, I couldn’t even imagine what it was like to actually play within the four walls of the Marvel sandbox with the rules lying within arm’s reach, and with millions of comic book readers ready to snatch me up by the throat—or at least write me a strongly worded letter—for every potential misstep I may have taken while guiding the steps of their favorite characters. Thankfully, Marvel Comics current executive editor and senior vice president of publishing Tom Brevoort told me exactly what that environment felt like.

Splice Today: Were the handbooks a helpful tool for the Marvel writing team to use when they planned out each issue, or do you think the writers felt restricted by them in some respects?

Tom Brevoort: I don’t think they were restrictive at all. If anything was restrictive, it was the predilections of individual editors. They were definitely a useful reference tool. Every office had one and they got used on a daily basis. Nobody wrote their stories based on the handbook entries. Nobody sat down and said, “I’m gonna have the Wrecker fight Iron Man, so let me look up all the stats first, and then I’ll know who wins.” That’s not how we do storytelling. Iron Man is going to win that bout because Iron Man has the logo on the cover. That’s true if it’s Iron Man, Captain America, Daredevil or the Hulk. They have an unfair advantage because they are the title character. It’s not necessarily about who is going to be able to beat up whom; it’s how. It’s the adventure. How do the characters deal with conflict and tension? How do they problem solve? How do they deal with the difficulties in their own lives?

Again, nobody used the handbook that specifically. To be honest, people didn’t even really use it to check the heights of characters. You can see that particularly in the 1990s with depictions of Wolverine—who theoretically is a short little guy because wolverines are small animals—but he was constantly being drawn like he was 6’2” or 6’3” because people liked big, heroic-looking superheroes.

ST: Do you get annoyed by the fact that so much of the discussion around the abilities of made-up characters or the debates about their capabilities gets grounded within what has essentially become a rule book?

TB: That was the one thing about the handbook that was a little bit unforeseen. I think over time going from the original handbook to the deluxe handbook to the master edition—which was about 10 to 15 years—Marvel and Mark spent a lot of time communicating to the audience that thinking about stuff this precisely and scientifically was important. Coming out of that, there are generations of fans for whom this nonsense is important. I don’t want to belittle or undermine that. It’s just that today no one thinks of it to that degree anymore. We still do handbooks, but they’re not that minutiae-driven, and we’re not as intimately worried about all of those details to the infinitesimal degree that Mark was, and that he instilled in the audience.

Mark was the mastermind behind those handbooks, and he did more work on them and was more heavily involved in them at every stage all throughout their existence than anyone else. They ate up a big chunk of his time editorially, and were consequently of greater importance to him than most others. But the handbooks did change how the real, hardcore, go-to-the-store-every-week-and-buy-comics audience viewed a lot of this stuff, so it had an impact. Once there were concrete numbers associated with characters, we’d get letters that said, “How can Spider-Man be having a hard time with the Tarantula, who’s just a guy! Spider-Man can lift 10 tons, man! It says so in the handbook!” By quantifying things so concretely, it changed the audience’s perception of what the characters could do.

ST: To that point, I loved the Thing. I would look at the handbook and see that the Hulk was clearly stronger than the Thing, but I’d also read that the Thing was trained in hand-to-hand combat, and strength isn’t necessarily everything in a fight, so that would get me thinking that the Thing might be able to get a win one of these days simply by using attributes outside of his raw strength. However, when I read debates online, the strength entry in the Marvel handbook is usually treated as an automatic, debate-ending argument to absolutely every potential conflict. That doesn’t strike me as what the handbooks were intended to do.

TB: You can’t control how the audience is going to respond to something that you do. What you said there is exactly right: There are plenty of places where people will quote the stats and say, “So and so couldn’t beat such and such.” The reality is, particularly if you think about it in terms of sports, which I think is the closest analogy, let’s say boxing. We’re going to have a fight tonight between two boxers. We can measure how much they can lift, and how fast they can run, and how many punches they can throw in an hour. If you put those two guys in the ring 10 times, you’re going to get 10 different fights with 10 different outcomes.

It’s true that one guy is probably going to win more than the other, but the other guy is going to win a couple of times because in each particular fight, there are all sorts of X factors: How fresh or how tired are they? Who scores a lucky punch? Who wants it more in that moment? Whose girlfriend just broke up with them the night before? If all you needed were the stats, we wouldn’t bother to have football games. We’d trudge the players out, they’d all stand there holding up their stat cards, and we’d count them up and say, “Yeah, that team has a higher overall number; they win!” That’s not the reality of this.

ST: Is there an ideal way to control story elements other than the handbooks? Is there some method for keeping these critical elements reined in so that some of the supposed unbreakable rules of the Marvel Universe aren’t broken during the telling of stories?

TB: I don’t think the handbooks presented a problem per se, and I think it was always valuable and handy to have all that information and reference material available, not just with respect to what people could lift, but also the histories of the characters. Here’s who this person is, what they do, here’s why they do it, and here’s what they’ve done up to this point. As somebody trying to write or edit stories with these characters, having all of that information in one easily accessible place is valuable. If a certain percentage of the audience applies that information in a way that wasn’t the way we did, it doesn’t matter. We still make the stories the way we make them.

When you get down to it, there will be some people who’ll be upset that their favorite character got beaten by their second favorite character, and before there was a handbook, there was still that sort of thing going on. I think there’s still value in the handbook as a reference source. Now that we live in the world of the internet where so much of this stuff is available online—and you always have the problem of bad data that you can pick up on—there’s less of a need to have a set of bound books in your office to do this on. If I need a reference on something, I can look for it online and then pull it out of the old book it was in. So there’s not as much of a need editorially for that sort of reference-based publication anymore. The in-house portion has gone away, and the out-of-house portion has also gone away to a large degree. We’ve seen the sales of handbook-like books taper down from the heyday of the 1980s and 90s. It’s not like they don’t sell, but the audience is more concentrated and specific, especially because part of that information they can just get online.