Since Robert Bolano’s death in 2003 at the age of 50, Farrar, Straus and Giroux and New Directions Press have been scrambling to get their hands on any publishable material by the great Chilean author. He’s proven to be a cash cow for those two publishers, especially since the English translation of The Savage Detectives was released in 2007.

FSG published 2666 and The Savage Detectives, both of which made The New York Times' Top 10 books of the year. Anything by Bolano is the best stuff coming out of New Directions at the moment and probably will be for a long time to come (they claim to have five more titles forthcoming). A bunch of unpublished stuff was just unearthed among Bolano’s papers last year, including what might be a sixth book of 2666. New Directions, noticing an emerging market for these new Latin American novels, has also opened the watershed for some lesser Bolano contemporaries, including Cesar Aira.

Twelve of Bolano’s books have been published in English so far; New Directions responsible for 10, which are smaller, at an average of 200 pages (2666 is almost 1,000) with more singular thrusts. (The larger novels are sprawling webs.)

The Return, translated by Chris Andrews (New Directions Press, $23.95) is the 12th book, released on July 6. It’s his second collection of short stories (the first is called Last Evenings on Earth), many of which, like “Prefigurations of Lalo Cura” and “William Burns” and “Clara” appeared in The New Yorker over the last year.

The Return, like Antwerp before it, reads in some places like a book hastily put together in the interest of holding an already rapt audience’s attention. It doesn’t have the same emphasis on unity and arc and symmetry that Last Evenings does, but for Bolano’s fans it will be just as thrilling.

The trouble with posthumous work, and especially with someone as popular as Bolano, is that you never know what was intended to be published and what’s just private notes, or character sketches (one novella, Amulet, is included almost entirely in The Savage Detectives) and I get the feeling that the editor’s scalpel touched upon these stories more than on previous works. (Each story is roughly the same number of pages and end with similar short, terse flourishes.) I’m certain that were Bolano still alive he would not have wanted this book published—his literary estate, publisher and academia, however, are another matter.

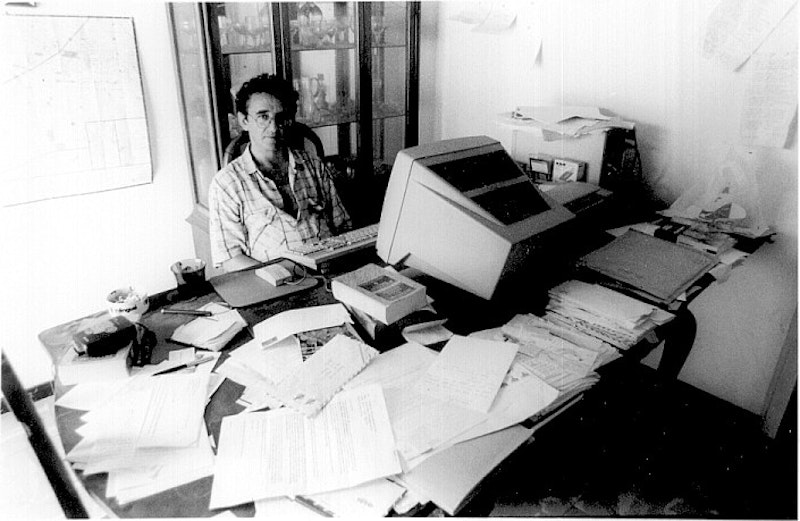

It is worth the $23.95 for one story in particular, though, that showcases Bolano’s sheer stamina when it comes to writing his characters (purportedly, Bolano used to write for 20, 40 hours at a time before passing out and then waking up and doing it all over again) and his breadth of reference, both in content and cosmopolitanism is staggering. The story is called “Joanna Silvestri” and is in the voice of an aging Italian porn starlet, telling the story of returning to Los Angeles to shoot a few movies and to visit a porn star named Jack Holmes, who is presumably dying of AIDS. There is not a single paragraph break in the entirety of the story. Although filled with graphic sex scenes, the story itself is profoundly unsexy and sad. Notice how he takes on Joan Didion and Brett Easton Ellis’s Los Angeles tone of ennui here:

Jack lived near Monrovia, in a shabby old bungalow that was practically falling down, and I told them I wanted to go see Jack however hard it might be, and Robbie said, Take my Porsche, you can have it as long you turn up on time tomorrow, and I kissed Ronnie and Robbie and got into the Porsche and started driving through the streets of Los Angeles, which had just begun to succumb to the night, the cloak of night falling, like in a song by Nicola Di Bari, or the wheels of the night rolling on, and I didn’t want to put on any music, though I have to admit I was tempted by Robbie’s sound system--CD or laser-disc or ultrasound or something—but I didn’t need music, it was enough to step on the accelerator feel the hum of the engine; I must have got lost at least a dozen times, and the hours went by and every time I asked someone the best way to get to Monrovia I felt freer, like I didn’t care if I spent the whole night driving around in the Porsche, and twice I even caught myself singing, and finally I got to Pasadena, and from there I took Highway 210 to Monrovia, where I spent another hour looking for Jack’s place, and when I found his bungalow, after midnight, I sat in the car for a while, unable and unwilling to get out, looking at myself in the mirror, with my hair in a mess and my face as well, my eyeliner had run and my lipstick was smudged and there was dust from the road on my cheeks, as if I’d run all the way and not come in Robbie Pantoliano’s Porsche, or as if I’d been crying, but in fact my eyes were dry (a little bit red maybe, but dry), and my hands were steady and I felt like laughing, as if my food at the beachside restaurant had been spiked with some kind of drug, and I’d only just realized and accepted that I was high or extremely happy.

When I read Bolano and passages like the one above, I imagine him like Philip Nolan, the protagonist of the Edward Everett Hale short story “The Man Without a Country” adrift between the continents, never able to return home, gazing at a dark and cold and glittering sea of prose.