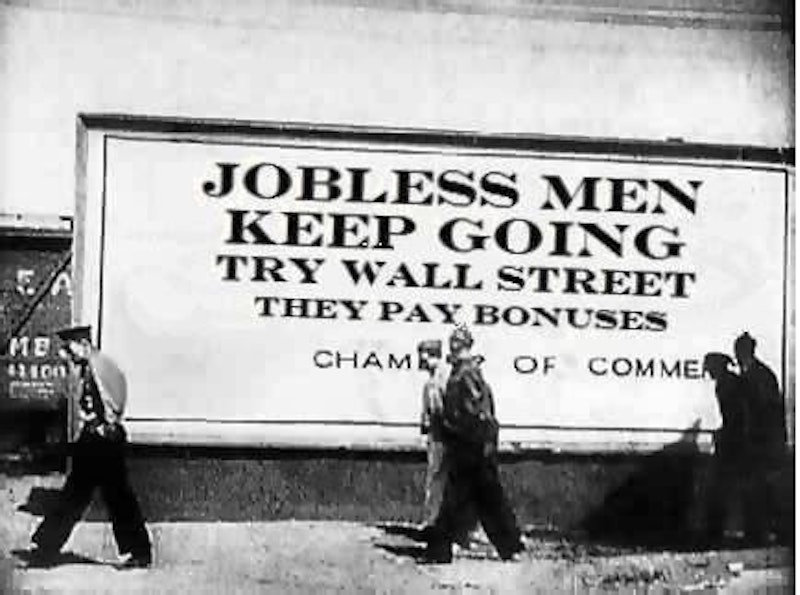

The Ask (Farrar, Straus and Giroux; $25.00) by Sam Lipsyte is ripe for this historical moment, the current mood and economic climate. Lipsyte is hilarious while also technically brilliant (he teaches creative writing at Columbia) so reading his book gives you a sense of accomplishing something while also being self-indulgent and unproductive at the same time. In short, it should make a great summer read, especially if you’re stuck in some steaming metropolis and out of work.

The first lines of The Ask read,

America, said Horace, the office temp, was a run-down and demented pimp. Whither that frost-nerved, diamond-fanged hustler who'd stormed Normandy, dick-smacked the Soviets, turned out such firm emerging market flesh? Now our nation slumped in the pool hall, some gummy coot with a pint of Mad Dog and soggy yellow eyes, just another mark for the juvenile wolves.

Our man Milo is a Development Officer at a third-tier liberal arts college in New York. He’s just been fired for pissing off the daughter of a wealthy benefactor and also being dead weight on the money-raising train that is the development world. “The ask,” in the parlance of the development world, is the numerical figure one hopes to acquire from a donor and Milo is offered his job back on the condition that he can engineer a gift of considerable size. The rub? The donor is a friend of Milo’s from college, Purdy, a blueblood and independently wealthy; Purdy has requested that Milo specifically handle the gift. Milo soon finds out, however, that Purdy has ulterior motives in enlisting his help. What follows is a disturbing and hilarious ride into the underground world of obscene NYC wealth of the hedge fund variety (à la Eyes Wide Shut, but not nearly as sinister) as well as the bathed-in-daylight world of the borough-dwelling unemployed (a contractor with high hopes for a death-row last meal cooking show and irritable Montessori school/cheese co-op founders abound).

Milo finds out that Purdy has an illegitimate child, Don, who’s trying to blackmail Purdy for something a lot more valuable than money, at least in New York City: face. Don threatens to ruin Purdy’s slick veneer. An Iraq veteran, Don is Lipsyte’s searing indictment of American foreign policy of the last eight years; if Don is the bastard child of a wealthy socialite, swept under the carpet for the sake of social graces, then Iraq is the bastard child of American greed, marginalized to keep the whole ugly machine going. Don is an amputee and extremely bitter about the way his country (and father) has neglected him. He’s also a heroin addict. He’s the type of character that causes you to wince:

“Purdy doesn’t know a thing about the world I come from. The world his fucking son comes from.”

“This is really about his wife.”

“Melinda? She’s okay. Just another rich bitch. Maybe I should take them all out. I’ve got PTSD. Got papers on it. Maybe I could do that. Live rent-free in a psych ward the rest of my life.”

“Don’t do that.”

“No?”

“Would Nathalie want that?”

“Would she want me to take the money?”

“I don’t know.”

“No, you don’t. You don’t know at all. Tell them I’ll sleep on it. Which means I’ll get high on it. Maybe the dragon will whisper the answer to me.”

The most attractive thing about Lipsyte is his humor. I first came to him in 2004 when a friend recommended his novel Homeland. Homeland is a really good read and is also about unemployment and a specific type of American male loserism—the book is written in epistles which the main character sends to his high school alumni newsletter, from his parent’s basement, that go unpublished; some critics might call them “irreverent,” but since it’s hard to be shocking today in any form, I’ll just say that Homeland is “poignant” and leave it at that, especially if you’re a recent to not-so-recent college graduate (living in your parents’ basement).

But this book is for an older crowd. It’s not just about privilege, the world of private wealth management and the fallout of the Iraq war. Milo’s son Bernie is a strong character in the novel, alight with childish perceptions in a world beyond his reach. It’s also about marriage and fatherhood. Take this passage about a failed foursome,

Constance, I’d just turned abruptly away from her, seeing something better in whatever Lena’s adulterous hunger could deliver. I’d almost let Maura drift off a few times, too, before Bernie reversed the inertia. We’d been off and on for ten years, Maura and I, had tried very hard not to be the love of each other’s life. It was like the stupid movie, without the cute bits.

Not one of the cute bits, for instance, was the night we had a foursome with a lascivious couple whose Greenpoint loft, perhaps because of the hillocks of cocaine on the coffee table, we found ourselves the last to leave. After some preliminary dialogue that wanted so much to parody the clunky verbal vamping of vintage porn, but had veered into grim, jaw-grinding consequentiality, Maura and the other woman had stripped and entangled themselves on the bed, all pinches and strokes and theatrical licks. Even through the fog of powders and booze, the sight of them aroused me and I turned to grin at the other guy. He smiled back, held up a palm for a louche, almost Wonderlandish high five. I shoved my tongue in his mouth. Really, I just meant to be friendly, to compliment the writhings beneath us, complete servicing circuit, but suddenly it seemed I’d broken the sacred swinger’s code.

“What the fuck,” the guy said. He pulled away, wiped his lips. Then he stuck himself in my wife, glared as he pumped.

“I’m not into that,” he said. “You had no right.”

And this passage, after Milo loses Bernie in a park,

I found Bernie, or he found me, his wrist in the grip of a stout woman in a business suit.

“Yours?”

“Bernie,” I said. “You’re in big trouble. Thanks.”

“No worries,” said the woman. “He was just chasing a pigeon.”

“Thanks again. I really appreciate it.”

“I’ve got three at home.”

“Pigeons?”

“No, kids. Here”

She handed me Bernie’s wrist.

“He’s a fast one. But I know how to sneak up on them.”

“I owe you,” I said, dragging Bernie away.

We behind a tree at the edge of the park.

“What are you doing, Daddy?”

“I think I’m going to cry,” I said.

“Don’t do that,” said Bernie.

“Okay,” I said, picked him up, laid my cheek on his shoulder.

“Bernie,” I said. “I love you so much.”

“That’s nice, Daddy.”

“Yes,” I said. “It is nice.”

“You want to know something else nice?”

“I sure do, Bernie.”

“I love Mommy’s friend Paul. Do you think Paul loves me, Daddy?”

They weren’t like dolls, because dolls had no feelings. Kids had feelings, just not any remotely related to yours.

Milo is a typical Caucasian pudgy and impotent American male, always fearful of his inability to please his wife and consumed by mommy issues. If Tony Soprano and Dilbert had a child, Milo would be it.

For some writers it can be difficult not to capitulate to the wealth that is their subject. John Cheever is one example; Clair Messud is another—writers for whom the bite-the-hand-that-feeds-you lesson has won out. Most of them want to exist in the liminal space of being tolerated by the people they write about (wealthy, vapid people) and the people they write for (also, wealthy, vapid people) and end up being the ideological bitch of a system that is ultimately exploitative and evil. I had an English teacher who criticized both F. Scott Fitzgerald and the narrator of The Great Gatsby, Nick Conway, for being the type of person that goes to a party and spends the whole time sneering at and criticizing everyone without realizing that they themselves are at the party. Sam Lipsyte, though, is not one such writer.

If you do find yourself with a lot of free times on your hands, this book could get a little uncanny—being unemployed while reading a book about what its like to be unemployed. The postmodern loop here is in danger of becoming a tautology that never ends; a wealthy New Yorker writing about the lives of wealthy New Yorkers.