It is customary, I have noticed, in publishing an autobiography to preface it with some sort of apology. But there are times, and surely the present is one of them, when to do so is manifestly unnecessary. In an age when every standard of decent conduct has either been torn down or is threatened with destruction; when every newspaper is daily reporting scenes of violence, divorce, and arson; when quite young girls smoke cigarettes and even, I am assured, sometimes cigars; when mature women, the mothers of unhappy children, enter the sea in one-piece bathing-costumes; and when married men, the heads of households, prefer the flicker of the cinematograph to the Athanasian Creed—then it is obviously a task, not to be justifiably avoided, to place some higher example before the world.

So begins the autobiography of Augustus Carp, a man of lofty ideals (often honored in inventive ways), compelling figure (of a rounder, scabbier sort), and boundless charm (in that his charm exceeds the modest bounds described by a small container, perhaps a thimble). Carp invites these parenthetical cavils because his opinion of himself in no way corresponds with reality. Carp judges himself to be quite splendid; his contemporaries find him loathsome on both a moral and physical level. The reader must object to Carp’s delusions, though he will doubtless enjoy reading them.

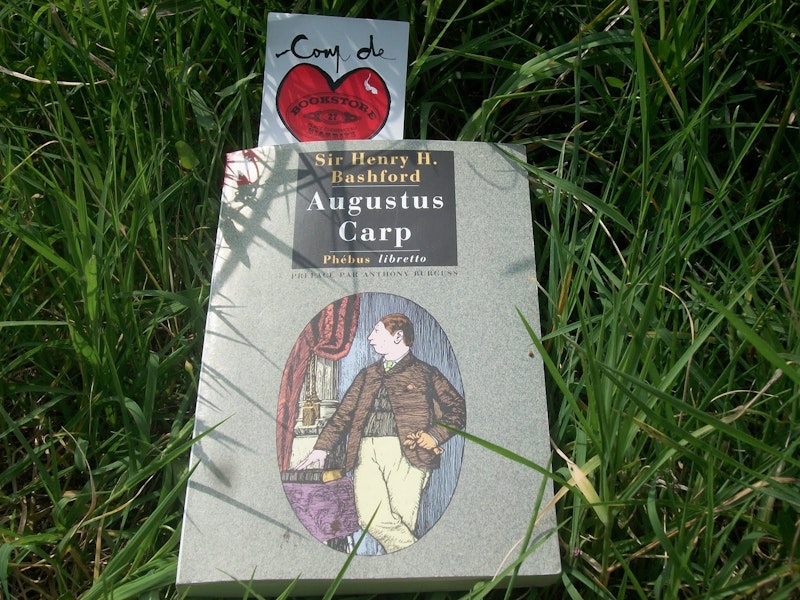

Carp’s autobiography, a satire written anonymously by Sir Henry Bashford (a physician to George V), details a middle class family in interwar London, and in a way it’s a lovely portrait of a particular place and time. The story charts Carp’s childhood (enlivened by an astonishingly verbose description of stone-skipping), his fervent embrace of religion (of a particularly sour sort), his education (a series of forced apologies from teachers), and his meteoric rise to mediocrity in the field of religious tract publishing. The plot has a classic simplicity and it never gets in Carp’s way.

Carp, the repulsive narrator, is the star of the show, and he is timeless. He is a literary character who embraces caricature and deadpan realism equally, like Bertie Wooster or Holden Caulfield. Carp is an oaf, an oaf who doesn’t understand his own oafishness; this is an old and reliable recipe for comedy.

Carp’s roots go back at least to Chaucer’s Pardoner, who presents an attractive show of religion to cover his inner putrescence, but Carp, unlike his forbearer, isn’t in on the joke. He has more in common with the blissful dullards of American sitcoms and cartoons—his closest contemporary analogue is Stan Smith, the endlessly thwarted ultra-conservative of Seth MacFarlane’s American Dad.

Carp, unlike the Pardoner, remains painfully sincere throughout his narrative, never admitting even a transient impulse to evil, insisting, in his grim pedantic way, that Providence ordained his every action, no matter how repugnant. We watch him rationalize his banality, venality, and concupiscence, as we would watch a contortionist at the circus; he retains an ecclesiastical solemnity throughout, whether he’s describing a game of Red Rover (Nuts in May, in the British context) or how his father dispensed with his aunts, and he never cracks a smile.

His hypocrisy becomes jewel-like, as intricately faceted as a cut diamond, and as durable—as a child Carp’s conscience set into a mold of Christian rectitude (understood in rather convoluted terms), and there it will stay, impervious to contrary information, legal setbacks, or the buffets of fortune. Carp and father are right, everyone else is wrong—mother Carp, by the way, haunts the margins of the narrative like a pale shade, floating in to deliver tea and nourishing meals and then blowing away like smoke on the breeze; her fate is deeply satisfying.

I have always found biography and autobiography rather boring, but Carp’s foray into the genre sparkles because he gets everything wrong—he has set out to examine his career and to explain the course of his life but he’s not up to task; he understands nothing. Carp finds a one-piece bathing suit morally repugnant but imagines that he has reached the heights of indulgent compassion when he offers to employ his mother as a cook after her husband’s death. He deplores the religious hypocrisy of his employer, Chrysostom Lorton, who publishes temperance tracts but drinks port—in fact Carp got the job by blackmailing Lorton’s wife, who he saw kissing her brother in law in the park.

Carp finds this public embrace, a central moment in the plot, deeply shocking. “For though I had been aware, of course, from my studies of Holy Scripture, that such things had occurred in the Middle East,” Carp tells us, “and had even deduced from contemporary newspapers their occasional survival in the British Islands, I had never dreamed it possible that here, in a public park in the Xtian London of my own experience, a married man could thus openly sit with his arm round a female who was not his wife.”

An uncharitable reader might think that Carp was spying on the pair, since he watches them while crouched behind a tree; oddly enough this notion does not occur to Carp, or to his father. Carp claims that the incident traumatized him, since his Christian (or “Xtian,” in Carp’s orthography) upbringing had shielded him from the horror of extramarital make-outs. Despite this carnal display Carp manages to choke back his tears and transcribe the pair’s conversation into a convenient notebook. When he confronts Mrs. Lorton with this oddly specific information she treats him like a scrofulous but essentially sweet puppy (Carp’s father has warned him that she might attempt to seduce him, a scenario that Mrs. Lorton finds unlikely). Carp demands that Mrs. Lorton must persuade Mr. Lorton to offer him a job:

“’You mean if he doesn't,'” she said, “`you'll tell him about me and Septimus.'”

“`As a Xtian gentleman,'” I said, “`it would become my duty.'”

Despite vast evidence to the contrary Carp retains an extremely high opinion of himself (to reveal the nature of this evidence would spoil the plot). In the same conversation with Mrs. Lorton Carp admits, “In my own circle […] I am not considered, I believe, to be unintelligent.” He cannot resist displaying his erudition and refinement through the constant inversion and re-arrangement of his subjects and objects, and by correcting everyone around him on both grammar and morality. A particularly tangled argument with his friend Ezekiel Stool about whether U counts as a vowel—is it “an union” or “a union”?—has the brio of a vaudeville act.

Carp speaks in the same voice for the entire novel, and Bashford shows a singular skill in keeping his creation’s tortured diction comprehensible and entertaining. We can tell that Bashford is in on the joke, even if poor Carp isn’t; after a while you learn to savor Mr. Carp’s peculiarly convoluted idiom. This is Bashford’s trick—he presents a boring and repulsive man who loves himself so completely that we become devoted to him. We never like Mr. Carp, and we applaud the misfortune that comes to him, but we also want to keep reading.

In the pantheon of memorable funny-talking literary characters Carp falls somewhere between Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster and Russell Hoban’s Riddley Walker (a post-apocalyptic narrator who uses phrases like “arga-warga”). Carp resembles Riddley more than Wooster; Wooster after all confines his weird talk to the occasional misunderstood literary allusion and “eggs and B.” In his introduction to the text Robert Robinson remarks that Carp emerges through his use of language, which is definitely spectacular but certainly not to be imitated. Carp’s morality and his diction intertwine—he is as needlessly and excessively correct in his writing as he is in his life, and in both fields he misses the point. For Carp, events don’t follow one another, tripping on each other’s heels with excessive familiarity; he separates them neatly with definite conclusions:

“This took place, according to our usual custom, immediately after the conclusion of our evening meal, and consisted of the singing by my father and myself of two or three hymns or sacred choruses, followed by the reading on the part of my father of a chapter of Holy Scripture, the whole being concluded by one of those extemporary prayers in the composition of which my father was so skilled.”

Anthony Burgess popularized Augustus Carp, though not too successfully, since it remains famous mostly for being unknown. Burgess also invented the Nadsat slang of A Clockwork Orange, another story that benefits from being told in a peculiar dialect. A Clockwork Orange’s Alex and Carp would find conversation difficult, since Carp’s appreciation of physical activity is confined to skipping stones (he thinks it should be Britain’s national sport) and Alex’s knowledge of the Bible is slight; neither one approves of alcohol, of course.

Perhaps we might imagine Alex’s unusual outfit augmented by Carp’s twin temperance badges, one reading N.S.L. (Non-Smoker’s League), the other S.P.S.D.T. (Society for the Prevention of the Strong Drink Trade; we may assume that Milk Plus would escape their attention). I like to think that Alex would refuse membership in Carp’s other solemn group of do-gooders, the Anti-Dramatic and Saltatory Union (Carp helpfully asterisks “Saltatory”—it means pertaining to dancing). Even in his mean way Alex knows how to have fun; Carp has eradicated the concept from his life, unless we count singing hymns with his father.

(Thanks to MAB for the recommendation. The book is easy to find used, but since the copyright expired long ago the complete text, with illustrations, is available online.)