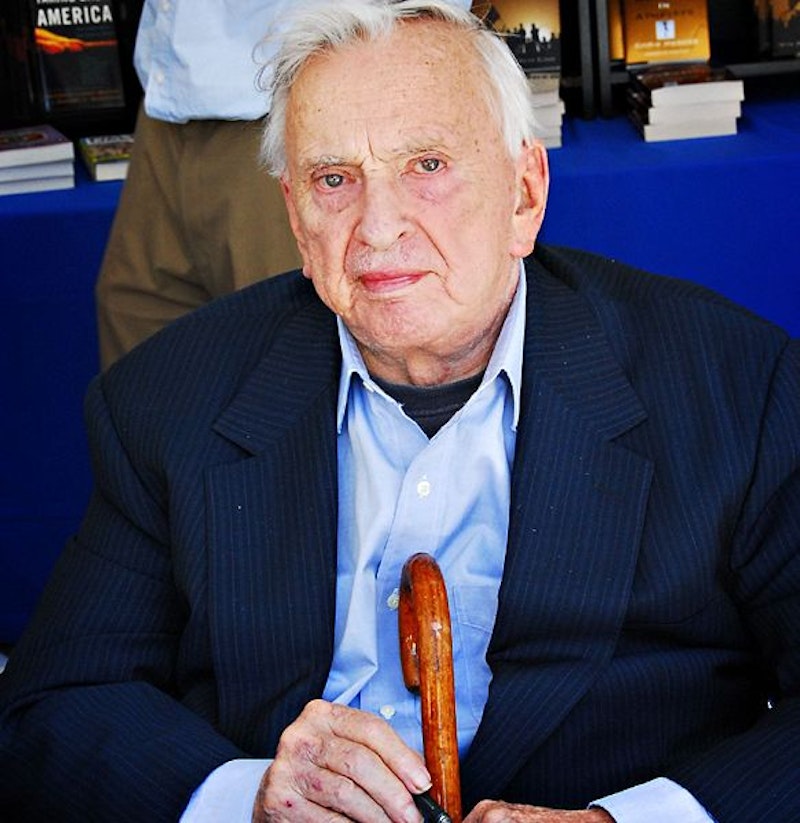

Gore Vidal, author and raconteur, is wheeled on stage at McGill University in Montreal. At age 85, he has settled into an existence as a head and a sack. The sack, which mainly takes the form of a white swell of shirtfront, is planted in a cherry-red wheel chair that has an attendant alongside it. Along the edges of the sack you catch sight of Vidal’s black suit jacket; beneath the sack you see his black-shoed feet and black suit pants, and a pair of white socks that travel a shocking distance in plain sight, climbing toward his knees.

The Vidal head is at the far other end of the sack, up on top. Peach and bronze in complexion, it’s capped by a silver wedge of hair with the same part seen in the hair of the young and middle-aged Vidal. The wedge has been shrunk down to make room for scalp and rides near the crown of the Vidal head. It provides a reassuring sign of continuity. In fact, it represents the peak of the entire Vidal apparatus. But it also looks stranded: the peach-bronze of Vidal’s brow travels quite a distance on its way to a hairline, just as the white socks had so far to go before reaching trouser cuffs.

Below the wedge, not immediately below but down a level, is the Vidal face. It is still a living thing, and for the next 75 minutes the eyes and mouth will be at work. Some people, no matter what kind of shape they’re in, belong in front of an audience. That’s Vidal, even now. He runs the evening, meaning that he does whatever he likes. “I don’t want to get too serious,” says his interviewer, a McGill professor of communications. “I don’t think you’ll be allowed to,” Vidal says. In effect, the monumental head and sack turn into a runaway goose, one that somehow also manages to be monumental.

Vidal hams away; in fact he clowns away. He brings up the royal wedding and pretends to be breathless: “Every time I look at the TV, there’s that boy, there’s that girl… and they’re adorable!” The interviewer says they’ll be Canada’s king and queen one day. “I know,” Vidal says. Then, hoarse: “… and how lucky you are.” A bit later, receiving a compliment from the professor, Vidal answers with a plummy “We do our best to give satisfaction.” When that gets a laugh, he spreads his arms wide. “What a nice audience,” he says.

But he sounds indulgent, not grateful. He’s doing what he likes, and he assumes it will result in the audience being entertained. Which is what makes him worth watching, this sense of the king who feels free to wallow in all the attention dumped on him, to splash about in it like Scrooge McDuck pelting himself with gold coins and thousand-dollar bills. That’s a monstre sacré for you, and the effect is the same when, as in this case, the monster appears to be zonked from medication, alcohol, or old age.

During their evening with Gore Vidal, the audience at McGill will hear him honk like a goose (in derision of H.G. Wells as historian), hear him refer to a mysterious “Miss Devlin who goes around the country saying ‘Gotcha,’” hear him forget the phrase “Don’t ask, don’t tell,” hear him brag twice about the same luncheon at the Kremlin alongside Pierre Trudeau and reveal twice that John Hays called Canada “Our Lady of the Snows” (the second time after an embarrassing build-up: “He had a nickname for your country. Would you like to know …?”). They will also hear him affirm that Barack Obama is a citizen, which is reasonable enough, but Vidal expands on this position by reminding us that Obama’s grandfather was “probably working as a Pullman car man. They had wonderful service in those days. His family was probably busy doing that.”

Vidal’s brain still has its moments. The American Revolution, Vidal says, was really just “an explosion of tax offenders.” Later, a plaintive European man in the audience says, “United States save the world from Nazzy people” (hisses from audience). Vidal: “That was an accident.” Vidal recalls boyhood skiing in Quebec’s mountains and says he’ll never be able to do it again. “The Laurentian Mountains are still there,” the interviewer tells him. Vidal (roaring): “Well, I’m not!” So his quip-making and phrase-making circuits can still fire. But the higher functions are shutting down, and the audience knows it.

People look at each other with the second “Our Lady of the Snows,” and they sag when the Kremlin story pops up again. But their mood revives. Vidal hasn’t noticed anything, and that’s all the fans need to climb back on board. Some of them have been waiting for an hour and a half, and it’s a relief for them that the evening’s show will stay intact, that Vidal is still laying down the law. And, after all, he says—or blurts or pronounces—things Canadians don’t mind hearing. These things all have to do with America.

To a young man who had asked something entirely different: “Ours is a country of the worst thieves who ever got together outside the Arabian Nights. I hate being American. Otherwise your question was wonderful.” A question or two later: “We have nothing to offer the world except lousy services, lousy goods and awful movies.” Later: “We have the most corrupt press on earth. You’re not doing so badly either.” And: “Americans are cut off from all information that might be useful to them.” At different times in the evening he tells the crowd that Harry S. Truman and George W. Bush was “our dumbest president.”

Nobody seems to notice that one. Maybe it’s too satisfying to hear the crunch of “dumbest” landing atop a famous American name. Vidal himself appears to like “dumbest” (“Giving advice is the dumbest thing you can do,” he says to an earnest boy student who wants guidance), and he’s grand about deciding who is and isn’t smart (Alexander Hamilton was “the only intelligent person in the country”). Monstres sacrés intellectual division, talk like ninth-graders in a competitive-admittance school program, especially ill-natured monstres sacrés at the end of a long day or the end of a life. So the audience at McGill gets its show, but it has to put up with a good deal of ill grace.

Admittedly, to judge by the people asking questions from the audience, most of the members are too muddled and self-involved to be worth anyone’s time. But Vidal also swats aside the few sensible questions. Someone asks him to grade the performance of the current American president. Vidal: “Oh, I don’t care. For God’s sake, he’s a minor figure in history, about as minor as you can get.” The goose is not pleasant, and its greatest interest appears to be making noise. “Honk honk honk,” to quote from his thoughts on H.G. Wells.

Above all, Vidal is bleak. Of the “Jewish-Arab situation,” to use Vidal’s term, he says, “Just ignore it, it will go away. And if it doesn’t, we will.” At another point he becomes reflective. “My people are the dumbest people on earth,” he says. “I only want them to get better. And I wait and wait and wait, and one day I shall die.”

He has one moment of quiet and sadness. The professor asks him if he’s covered fairly by the media, and Vidal says he takes no guff, then adds, “I don’t bite as well as I did, but I can still do it.” Saying this last bit, his voice drops and he sounds like he’s talking to himself. The impression, to be exact, is that of a man comforting an old and beloved beast that’s about to die. So there let us leave him.