By July 1776, demonstrations and riots had torn New York City for over a year. The Royal government had fled and nearly 75 percent of the population with it. Committees of public safety dominated by the Sons of Liberty and other radicals ruled the streets. An army of 23,000 insurgents held Manhattan.

On the morning of July 9, messengers from Congress in Philadelphia crossed the Hudson with dispatches and other papers for the army’s commander-in-chief, General George Washington. One of the documents was a copy of the Declaration of Independence, a policy statement that incidentally clarified Washington’s personal status. Until July 4, he’d been a rebel. Now he was a traitor.

He ordered six longhand copies made and distributed to his brigade commanders. Then he ordered Retreat—the ceremony that ends the military day—at six p.m., a half-hour earlier than usual. Most of his troops were bivouacked in the rolling wooded hills of what is now midtown. There ceremonies would be held wherever their commanders could find sufficiently large, flat, open spaces.

The two brigades encamped in lower Manhattan, in what was then the City proper, were ordered to form on the Common, which extended roughly from what is now the south end of City Hall Park to the south side of the intersection of Broadway and Park Row. By 5:30 p.m., the Commons was a chaos of dust, marching regiments, bellowed orders, rolling drums, and piercing fifes. Civilians drawn by the stir jammed the adjoining streets.

Up at headquarters, near today’s intersection of Varick and Charlton Sts., Washington mounted shortly before six p.m. for a brief ride to the Common. Now, at 44, he was six feet, two inches tall and weighed about 210 pounds. His face was ruddy, the clear, pale skin that burns rather than tans. He was remarkably strong and, save for his teeth, in fine health. He was so broad-shouldered that his uniform coats needed no padding. He sat easily and gracefully in the saddle: he was, as a fellow Virginian, Thomas Jefferson, said, “the finest horseman on the continent.”

He rode into the hollow square of soldiers amidst a cacophony of shouting men as company officers reported to regimental commanders, regimental commanders to brigade commanders, and brigade commanders to the commander-in-chief that all men were present or accounted for. “Then the formation was ordered to stand at ease,” Brice Bliven Jr. wrote in Under the Guns, “and it was quiet.”

Washington habitually wore an assumed expression of good-humored reserve. This was partially due to constant physical discomfort: his teeth hurt. More important was Washington’s belief that among the duties of a leader was projecting a serene image to his followers. He was naturally passionate and hot-tempered. Hence, he’d struggled from youth to conceal his emotions and generally succeeded. He occasionally showed irritation by withdrawal into an icy formality.

Only a few, such as General Charles Lee, whom Washington personally relieved of command on the battlefield after Lee bungled the opening of the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778, would taste the extraordinary, almost terrifying rage coiled within the Virginian: the sudden flush, the blue eyes narrowing to slate, the calm features contorting with contempt and anger, the voice so rarely raised above a conversational tone exploding in a grating roar, the savage words striking like the butt end of a bullwhip, the wrath that seemed, as one aide observed, to make the very leaves of the trees to shake.

But this wasn’t such a day. Retreat opened with routine announcements. The commander-in-chief approved sentences of flogging passed by courts-martial against deserters. The form of the passes for the Hudson River ferries had changed. Congress had authorized each regiment to have its own chaplain and pay him $33.33 a month.

Then, “in a very loud voice,” an aide-de-camp declaimed the document from Philadelphia. Thus New Yorkers first heard the words we live by: When in the Course of human Events…We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness…that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it…it is their Right, it is their Duty, to throw off such Government…A Prince whose Character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free people…And for the support of this declaration, with a firm Reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.

Then a chaplain read from the 80th Psalm (“Thou has brought a vine out of Egypt, Thou has cast out the heathen, and planted it”); the brigades gave three cheers; and the troops were dismissed.

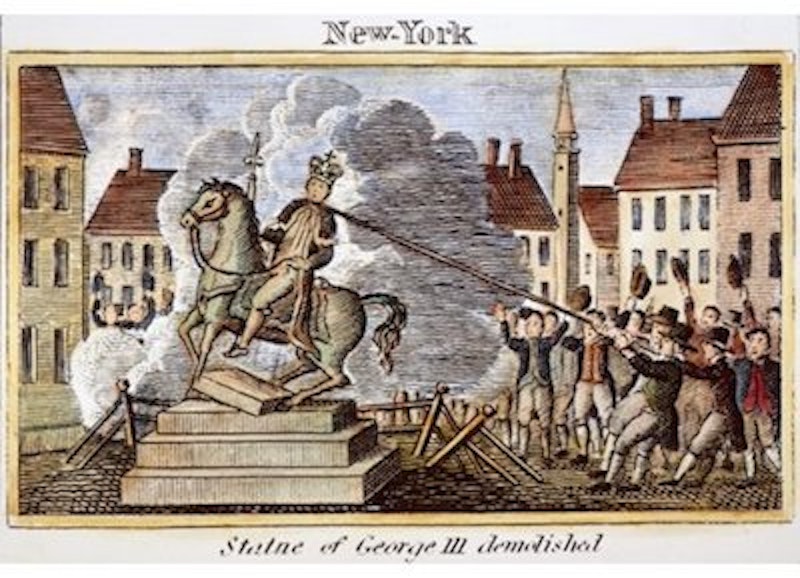

At twilight, a mob led by the Sons of Liberty quietly toppled the gilt-lead equestrian statue of King George III at Bowling Green. The Sons even sawed the royal crowns off the fence surrounding the Green: the fence is still there and the saw marks still visible.

Then they broke the statue into sections small enough to cart off to Litchfield, Connecticut where a foundry melted them into 42,088 bullets. As Ebenezer Hazard, the city’s first postmaster appointed by Congress, wrote: “[The King’s] troops will probably have melted Majesty fired at them.”