"I'm going to put myself to sleep now for a bit longer than usual. Call it Eternity." So wrote novelist Jerzy Kosinski in 1991 just before consuming drugs and alcohol and tying a plastic bag over his head in his bathtub. With his suicide at age 58, the Polish-born Kosinski joined Tadeusz Borowski, Jean Amery, Paul Celan and Primo Levi in the tragic club of Holocaust writers who couldn’t wait for death to come and take them.

One can only speculate on why Holocaust survivors fight against all odds to escape death while eventually succumbing to the urge to induce it themselves. When one has achieved so much after scrapping to put the ugly past in the rearview mirror—as Kosinski did—the question becomes all the more puzzling. Sometimes, though, when you scratch the glossy surface of success, what you find underneath is less shiny. Such is the case with Kosinski, whose once incandescent literary career had dimmed for years before he slipped that bag over his head.

Kosinski's immigrant success story in the U.S is one for the ages. A Polish Jew who survived the Holocaust by being sheltered by villagers, the Communism-hating Kosinski emigrated from Poland to this country in 1957 with little more than his prodigious talent and work ethic. He started off working odd jobs—among them, truck driver and movie projectionist—and by 1968 he’d won the National Book award for his novel Steps, a collection of vaguely related vignettes. His hit 1965 novel The Painted Bird, which made Kosinski's name as a literary figure, is a savage tale of a young Jewish boy wandering from village to village in Eastern Europe during WW2, witnessing various atrocities, which are committed by Polish peasants rather than Nazis. The only sympathetic character in the book is a Nazi SS officer. Kosinski's successful 1970 novel, the cult classic Being There, was made into a hit movie starring Peter Sellers.

Kosinski's work was often dark and explicit in its depiction of violence and sex, and its tone was of removed detachment, as if allowing any emotion might interfere with an objective chronicling of the human spirit’s underbelly. Despite the bleakness of the terrain, Kosinski's novels traversed, they caught on with readers. With three successful novels in rapid succession, Kosinski became a literary star.

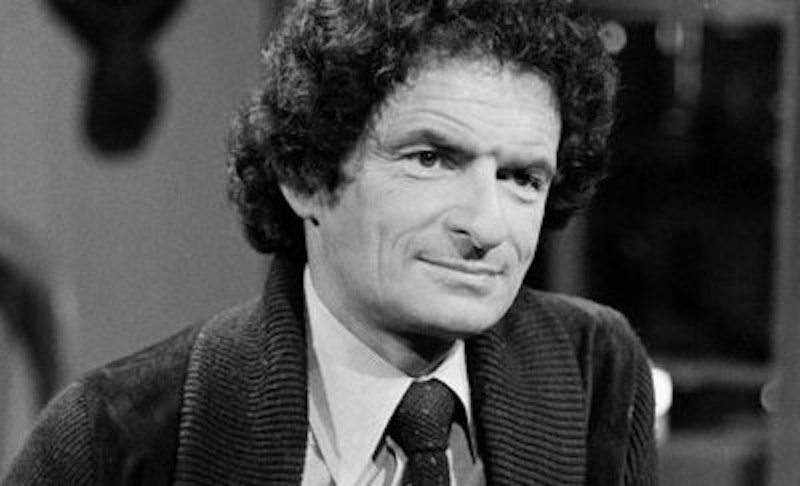

Far from the brooding recluse that his existential despair-filled novels might suggest, Kosinski was a warm, engaging and charismatic presence in public. He became a highly sought-after guest at all the best parties in Manhattan, and ended up appearing on Johnny Carson's Tonight Show 12 times. But even as his star was ascending, the seeds of Kosinski's demise were planted. Though noted Holocaust activist Elie Wiesel praised The Painted Bird in a New York Times book review, some witnesses to Kosinski's WW2 experiences in Poland were disputing the author's depiction of events. The dissenters said that, far from being persecuted by Polish peasants while wandering the countryside, Kosinski had been saved from the Nazis by them in the stability of their homes. The author's credibility problems had begun.

Then the Village Voice went after Kosinski in a piece headlined, "Jerzy Kosinski's Tainted Words." Kosinski was accused of hiring freelance editors to help him write his novels. The article's authors, Geoffrey Stokes and Elliot Fremont-Smith, also suggested Kosinski had written The Painted Bird in Polish and had it translated into English, though they offered no supporting evidence. A report came in from Warsaw claiming Kosinski had plagiarized a Polish book to write Being There. His literary reputation began to crumble, and Kosinski's politics didn't help him. As a strong individualist, he naturally recoiled against the ideology of Communism. This put him at odds with the substantial portion of the cultural elite in New York who were avowed leftists, sympathetic to the Stalinism of the Soviet Union. The inevitable rumors that Kosinski was working for the CIA also emerged. It was open season on Kosinski at that point.

As a perceived right-winger operating within a largely leftist culture, Kosinski probably wasn’t destined for fair treatment if a chink in his armor was detected. Unlike most American leftists, however, Kosinski actually had first-hand experience with Stalinism (in post-war Poland), and had legitimate reasons for despising it. His work declined after Being There, and, although he would publish six more novels, the quality of his work never regained its previous form.

Kosinski's art suffered after his reputation was called into question, but in a sense, his art was his life. Starting off with any job he could get after his arrival in the U.S., he eventually received a degree from Columbia and went on to lecture at Wesleyan, Princeton and Yale. Kosinski served two accomplished terms as chairman of P.E.N., the international writers organization, and even acted in the Warren Beatty film Reds, where he somehow received billing over Jack Nicholson. The polo-playing Kosinski prowled the sex clubs of post-midnight New York regularly, was on a first name basis with Henry Kissinger and a regular TV talk show guest. He achieved the sort of flamboyant profile that made certain jealous or pompously judgmental members of the literary establishment want to tear him down. Real writers were supposed to eschew the limelight for the solitary life of the writer if they were to achieve artistic purity.

Kosinski addressed some of the issues that hounded him in the introduction to the 1966 reissue of The Painted Bird. In it, he stated that well-intentioned people were claiming the novel was autobiographical and that they sought facts to back that up. Kosinski felt—like Bob Dylan—that people wanted him be a spokesman for his generation (of Holocaust survivors), but he rejected this. As an artist, he wanted to be free to interpret events as he saw them, not as others wished him to, and felt he’d earned that right. Facts, he argued, should not be used to determine the validity of his own personal interpretation of his wartime experiences.

Kosinski's health had been in decline, just as his reputation had been, by the time he took his life. He’d attended a party at writer Gay Talese's residence the night he did it, but gave no indication of what was to come. One of the most polarizing and electric literary figures of the 20th century had slipped out the back door without telling anyone, and he wasn't coming back.

—Follow Chris Beck on Twitter: @SubBeck