In 1979, after finishing college in New Jersey, Peter Honig moved to New York City. Not knowing what to do for money, he saw an ad in the New York Times looking for a taxi driver. With no experience and little knowledge of local streets, he contacted the Ann Service Corporation, one of the largest taxi companies in the city. The company did a background check on Honig and agreed to help him obtain a Hack License.

A Hack License allows a driver to operate a Yellow Medallion Taxi in the five boroughs of New York. A Medallion identifies a cab as part of the Taxi & Limousine Commission, the governing body of New York taxis. In those days, a Medallion cost $62,000. Today, the cost is over $800,000.

Honig passed the TLC written test, paid $30 and received his HACK license. He joined the ranks of 30,000 fellow cab drivers in the city. Most were American born men aged 40-50. There were a few Caribbean drivers and a large number of immigrant Russians who’d been doctors and lawyers in the old country. Honig, who played in a punk rock band, was among the small percentage of young musicians who drove cabs.

Drivers worked a 12-hour shift starting at 6am or 6pm. On Honig’s first day, he arrived in the morning to find a long line outside the Chelsea taxi station. He waited two hours only to be told there were no remaining cabs. The next day, he arrived a half-hour early but again failed to secure a cab. On his third day, a fellow driver told him to “grease” the dispatcher a five-dollar bill. This worked and Honig had his first cab.

Drivers were given two options regarding the lease payment. They could work for 40% of the meter total and the cab company paid for the gas, or they could pay $62 per day ($82 for a night shift) and pay for their own gas. Most rookies opted for the 40% option and the day shift since it was less intimidating.

“No one tells you what to do,” Honig says. “You’re given a cab and you just start driving.” In his first year, Honig stuck to picking up businessmen. Though they tipped poorly, they were safe and reliable. They also gave the driver specific directions helping Honig quickly learn the Manhattan streets.

Honig averaged between $50-$75 a shift his first year. (Today, New York taxi drivers average about $250 a day.) Though the work was relatively easy, Honig found it depressing and stressful. He couldn’t believe he’d spent four years in college to become a cab driver.

Honig settled into a routine. He picked up his cab at 6:00 am and headed uptown looking for fares. On a good day, he’d find a businessman on the Upper West Side needing a ride to Wall Street. From there, he’d take a fare to midtown then another passenger downtown. A typical 12-hour shift yielded 40-50 fairs and covered 200-250 miles.

Some passengers only traveled a few blocks. To Honig, these short rides were great. Since the meter started at $1.25 and ticked ten cents every 1/8 mile, the total added up quickly. A common misnomer is that cab drivers choose busy streets to jack up the meter, which is not true. Traffic is an enemy to taxi drivers and passengers alike. Time spent in traffic means less fares per day. Smooth sailing streets equate to more money and better tips.

Honig drove a Checker Cab. The Checker line was the most famous cab in America. The hulking sedans fit six people in the back and had a bulletproof partition between driver and passenger. Most of the cars were beat to hell and had no air conditioning, unreliable radios and inadequate shock absorbers. “I remember one car was so trashed, there was a hole in the floorboard,” Honig recounts. “Every time I hit the brakes, I saw asphalt flying by.”

On slow days, Honig and his fellow Checker cabbies often played demolition derby. “If we saw a driver taking a quick nap, we’d ram the back of his cab to give him a courtesy wake up call. We’d also make sure to knock off any passenger-side mirrors since the missing mirror was considered a badge of honor.”

After a year, Honig opted for night shifts realizing he could make more money and encounter less traffic. “It was scary at first. There were certain areas you avoided like Harlem, parts of Brooklyn and the Lower East Side. But nights were easier and more exciting.”

Honig perused high-end restaurants, nightclubs and bars. He found a niche among Japanese businessmen frequenting mahjong gambling parlors in Midtown. Many of the businessmen lived in Westchester County, a coup since once you left the city you could charge double what the meter read. These men also gave great tips.

“One time I was driving two Japanese guys on the Hudson River Parkway when I fell asleep behind the wheel. I was woken by the sound of a loud megaphone screaming, ‘WAKE UP!’ A police car had pulled beside me and noticed I was sleeping while driving 70mph down the highway. They must have had somewhere really important to go because they didn’t pull me over. I didn’t get much of a tip that night.”

Intoxicated passengers were a mixed bag. Sometimes they gave larger tips, sometimes they puked and soiled themselves. “Friday and Saturday nights were crazy. I had couples that had backseat sex, prostitutes who gave blow jobs to customers and junkies who shot up while I was driving. One time I picked up Billy Idol and his posse and we all smoked weed together.

“The first time I was robbed was halfway through my second year of driving. It was about 5:00 am and I’d had a great shift. I was at a red light at 44th and 8th Avenue near Times Square. I had a wad of cash between my legs and I was counting the night’s take. My window was open and there was a transvestite prostitute standing nearby. She asked, ‘Hey you. Can you tell me what time it is?’ As she talked, she walked toward the cab.

“As I looked at my watch she reached into the cab, grabbed all my cash and started running. I got out and ran after her but she had too big a head start. So I got back in the cab and drove after her. Unfortunately I didn’t close my door all the way. I chased her up 44th Street and hit the gas to make it through a red light. As I took a tight turn, the door opened and the momentum propelled me out of the cab tumbling into the street. I looked up to see my cab smash into the wall of a XXX Theater. The transvestite disappeared into a nearby alley. I limped back to my cab. The bumper was trashed but the engine was still running so I was able to drive to the station. I had to pay back the $250 out of my own pocket.”

Honig was robbed several more times in the next few years. One night, he made the mistake of driving a guy to score drugs on the Lower East Side. As he waited for his passenger to return, two Puerto Ricans approached him. They stuck a knife in his face and made him get out of the cab. “Take it easy,” they said. “We just want your money. Don’t fuck around and you won’t get stabbed.”

Honig hid his money in a hole in the sun visor. He told the men he had no cash since he was just starting his shift. They didn’t believe him. They searched the car, looking in the glove box, under the seats, beneath the floor mats. At the last moment, one of the guys slammed the visor and a wad of cash spilled out.

The guy with the knife yelled, “You motherfucker” and stabbed Honig in the stomach. Fortunately the wound was not deep. Honig returned his cab to the station then had a friend drop him at the Emergency Hospital. He received several stitches and still has a scar to this day.

Honig’s worst cabbie experience came in 1981. It was early morning and he was coasting down 7th Avenue when he heard a loud thud on the right side of his car. He stopped the cab and got out. He saw a pile of garbage in the street and figured he’d hit a trashcan. As he approached the garbage, he realized it had eyes. He’d hit a bag lady. The woman was short and appeared to be in her seventies. She was completely motionless and silent.

Honig found a payphone and called the police. By the time they arrived, the bag lady was dead. A witness came forth and told police the woman had tried to jump in front of a trash truck and another taxi earlier that same night. The cops told Honig the woman likely committed suicide and he was not to blame. Regardless, Honig was despondent. He took several weeks off before he was ready to drive again.

By 1983, Honig tired of the grind of the continual 12-hour night shifts. “The things that once seemed exciting--the grime, the edge, the seediness—had become depressing. I’d become a vampire and had developed some very unhealthy habits. Plus, the city started harassing drivers, making sure we kept proper trip sheets and had up to date paperwork. It took the fun out of the job. And once the fun was gone, being a cabbie was kind of a drag.”

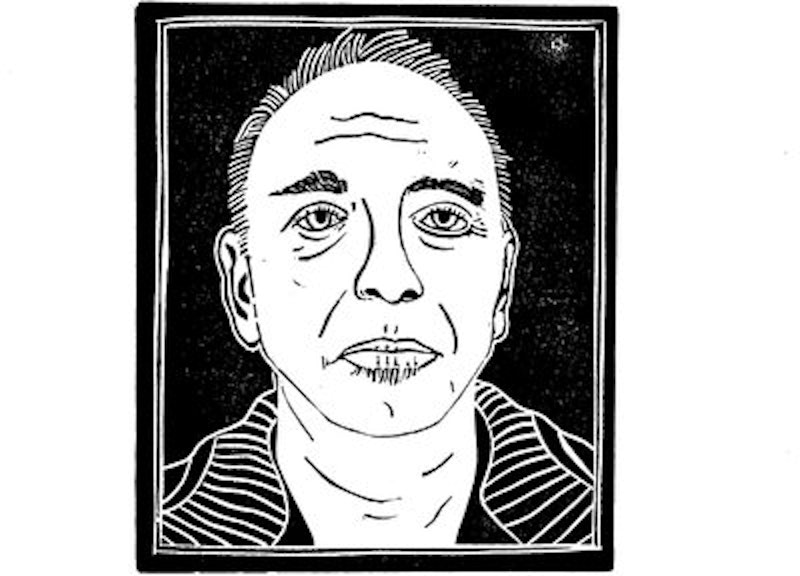

—See more Loren Kantor at his blog.