Edward I. Jacks, the once-famous 1950s “prose poet” sometimes lumped in with the Beats, with whom he shared some aesthetic characteristics, but also sometimes thought of as a forerunner to the later “trash verse”/”plundercore” scene of the Midwest, is little known to most readers—even those who might consider themselves to be enthusiasts of fairly obscure poetry—these days, but to those to whom he is known, the writer of the collection Pieces of a Broken Dream is a lodestar.

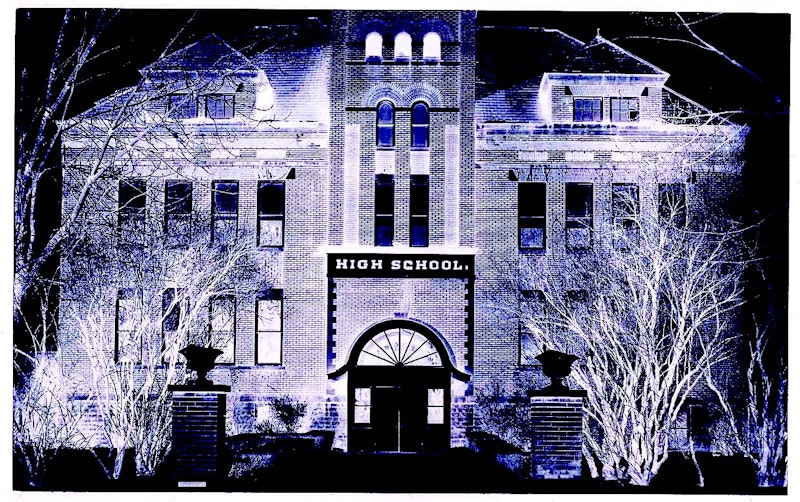

More specifically, a passage from the piece “I See Your Air Burning” became a rallying cry for aficionados of the upper Midwest’s music and arts scene of the late-1950s: “School’s cool if yr a tool or a fool.” Ironically, many who took to this phrase most energetically were themselves college or even high school students, perhaps finding a sort of resonance in the words as they seemed to pertain to these young people’s frustrations or disillusionment with their educational experiences. To the degree that Mr. Jacks retains any popularity in the present, it seems as if it’s due to the “School’s cool…” aphorism having been revived by a new generation of young Americans, saddled with seemingly insurmountable student loan debts taken on in pursuit of what have too often turned out to be useless degrees.

“Well… what do you think?” Emily Twiggs asked, wringing her thin hands behind her back. “I know, it’s not much, but is it, you know, a start?”

Harry Leeds barely glanced up from the Sega GameGear in his hands, in mid-mutter about something like, “Fuckin’ hedgehog won’t grab the goddamn wrings.” He exhaled sharply through clenched teeth and set the GameGear down roughly on his desk. After stewing silently for a moment he forced a smile and regarded Emily with polite indifference. “Uh, yeah, it’s not bad. I’ll run it on the front page of the ‘Arts’ section, ‘kay? How’s that?”

Emily was both confused and a little giddy—torn, you might say. “That’s… great, Mr. Leeds, but it’s… not done. And I thought this was a magazine?”

“Harry,” he said, now looking her over and really seeing her for the first time, a reptilian smile creeping across his face.

“I’m… sorry, sir?” Emily asked awkwardly.

He stood, tucked his shirt in, adjusted his belt and made his way round to the front of the desk, sized the new writer up more closely. “Call me Harry, toots. Everyone does,” putting his arm around her and giving her a little squeeze that elicited a nervous laugh. “And you let me worry about just what it is that Moustache Publishing produces, alright? I am the Manager or whatever, after all, right?”

Emily pulled away to the degree she could without making a fuss and agreed with an “Mm-hmm, yep” that Leeds was in fact the Manager, or whatever.

“Good,” he said, taking what he believed to be a discreet whiff of the young woman after what he’d thought was a warmly supportive squeeze. “Drop it off with that blockheaded fellow—what’s his name—Berkman. Drop it off with Berkman and tell him to do one of his ‘special edits’ so it’s ready to run, okay?”

Though Emily was more than a little uncomfortable on top of her mounting confusion, she was excited about her first story making it to print, and before she’d even finished writing it! “Berkman,” she repeated. “‘Special edit.’”

Leeds smiled and walked to the door, opening it and gesticulating ostentatiously as he did. As Emily approached, he stepped in front, put his hand on the frame so his arm blocked her way. His snakelike slime gave way to a wolfish grin. “And howzabout we get some chow to celebrate your big break?” he “asked,” wiggling his eyebrows.

Emily crossed her arms over her chest, her Jacks “story” clutched close. She smiled hesitantly as she tried to buy time to come up with some excuse to decline. “I… my… mother…”

“Well, if you’ve got other plans, I suppose the story could…” his smile began to fade as his voice trailed off.

“No!” Emily interjected. “No, I… would… love to… go… eat… with you,” she said like a malfunctioning automaton.

Leeds’ smile returned. He withdrew his arm and primped his slicked-back hair a little. “Terrific. Meet you in the lobby at 5.”

Emily, feeling a bit lightheaded, gave a thin smile as her reply, and then stepped out quickly. Leeds checked out her figure, giving himself a little “Eh, not bad” and straightened his tie. “Oh, Em?” he called after her. She turned stiffly. “Congrats, babe,” he said, winking afterward.

Brian Powell finished pumping the measley $4.73 into his shitty Ford Focus and climbed in. The car reeked of stale cigarettes and cheap, chain-store pizza. He looked over at the stacked boxes of Papa John’s garlic butter sauce cups, wanting nothing more than to hurl them into oncoming traffic—no, to hurl them into the very heart of the Earth’s yellow sun. Instead, he moaned in anguish and counted what remained of the week’s pizza tip earnings after the $500 he had set aside and put into an envelope bearing the Papa John’s logo and the words “For Mistress M. McCleary” in his handwriting: $21.43. The $0.43 had been courtesy of a University of Knowledge student who’d cuffed him on the shoulder, called him “bud” and “man” and assured him that he “really appreciated it.” “This is bullshit!” Powell hissed impotently. Then he drove over to Maggie McCleary’s fortified compound and handed over his earnings and the garlic butter supply like a good little boy. As a parting shot, one of the guards at the gate detained him briefly to inquire: “Say boss man, you got any extra pizzas in there? Rather have one with pepperoni but if alls you got is a supreme or summ’in’ that’s okay too, I guess.” $21.43 after a week of this shit. This was no way to live.

“Are you Oliver Berkman?” Emily asked the broad back that faced her after knocking lightly on the desk.

“Oscar,” the figure corrected her as he turned to face her. “Oscar Berkman,” the burly, bespectacled, recently disgraced reporter added. Realizing by her expression (and botching his name) that the thin, attractive brunette before him was somehow unfamiliar with the story of his rescinded Pultizer and his branding as a “literal misogynist” for wondering if Pop idol Jayla Ba-Bing!’s bodyguards had gone too far by beating to death a cabbie who had heard “#RegularKween” Ms. Ba-Bing! say “regular guys” were welcome to ask her out “as long as they [were] nice” and decided to greet her from a distance of 25 feet or so, Berkman’s hard expression and harsh tone softened. He extended a meaty hand. “Oh, you’re the new writer. Nice to meet you.”

Emily shook his hand. “Yes, I am. I was, um, told to,” she passed him the paper she held suddenly. He glanced at it, then at her, then took it with a chuckle. She sort of tisked and put her palm to her forehead, “Gosh, I’m such an airhead. I’m Emily. Emily Twiggs.”

Berkman smiled and looked the paper over quickly. “This is a pretty good start—I’ve heard people talking about Jacks. The kids and all.”

He made to hand the paper back but stopped upon noticing her frown. “Was there, uh, something else?”

“Just that… I thought,” she rubbed her neck absently before her eyes widened and she said sharply, “Oh! It’s—I’m supposed to tell you ‘do a special.’” She touched a thin forefinger to her chin, then pointed, nodded and smiled: “‘Your special edit,’ that’s it, that’s what Mr. Leeds said,” she smiled and laughed a little. “Sorry, I just --”

Berkman’s manner became brusque. “Oh. Got it.” He put the paper on his crowded desk. “I’ll get right on it. Good meeting you, Emily.”

“You too,” she replied, her smile running away. As she started to leave she asked, “Is… everything okay? Did I…?”

“It’s…” he stopped abruptly, shook his head and smiled, something sad in his face. His demeanor again eased and relaxed, “No, no, I’m just busy. Busy and tired.”

“Try not to work too hard,” Emily said, giving him a friendly look and a wave as she left.

Berkman watched her exit the bullpen area. He was still standing in front of his desk, lost in thought when The Chief came sauntering up.

“Who’s the new skirt?” The Chief asked—barked, really—as he nibbled on an unfiltered Camel.

The Chief looked somewhat like an older, squatter, significantly heavier Berkman; he wore khaki slacks and a short-sleeved button-up, both of which seemed a size or more too small for him and further accentuated the roundness of his physique. Like Berkman, The Chief had recently suffered a setback in his professional life; he’d been the face of Moustache Publishing for as long as anyone could remember, but had announced suddenly some weeks ago that “corporate”—heretofore completely unmentioned by and unknown to anyone at the tiny shoebox operation where the small staff pounded out ream after ream of “content,” with The Chief their version of O’Neill’s “Yank” from The Hairy Ape, urging his team of “content generators” to “bang it out” and “punch those keys, ya sissies!”—demoted him after decades to the position of mere Editor.

No one was actually sure if this was, in fact, a demotion or not since The Chief had always simply been known as “The Chief” and continued to be referred to as such despite now having a desk in the back corner of the bullpen with an “Editor” plate rather than an office, now taken up by the newly arrived Leeds, who it was thought was now “Manager,” although this was unconfirmed and based purely on office scuttlebutt. At any rate, everyone was relieved that The Chief was facing his existential crisis more calmly than did O’Neill’s famous stoker character, because The Chief would likely have met just as bad if not worse an end in a bout with an ape, given his age and obesity. Berkman had noticed he’d picked up at least one bad habit again, though.

“I thought you quit, Chief,” Berkman gestured vaguely toward the cigarette the older man was gnoshing.

“What’re you, my mother?” The Chief jabbed, swallowing what remained of the Camel. It was rumored that he’d started eating cigarettes the first time back when the rash of indoor smoking bans had begun, but as far as Berkman remembered he’d always eaten them. Snorted them occasionally, too. The Chief nudged Berkman with a knobby elbow. “I said who’s the skirt?”

Berkman seemed lost in thought. “Hmm? Oh, uh, Emily something. Twiggs, I think.”

The Chief’s mug stretched into a wry grin. “You ‘think,’ huh? Sure,” he dragged out this last syllable and then laughed raspily. “You got the hots on for her, don’t’cha?” he slid another Camel out of the crumpled pack and took a hearty bite, stalking after Berkman like a cat after prey.

“I don’t even know her, Chief,” Berkman protested unconvincingly, taking a seat and picking up the paper Twiggs had given him.

The Chief pointed his stubby ring and little fingers at Berkman as he pinched the remains of his half-eaten cig between his thumb and index. “I know you!” he said boisterously, but his demeanor quickly became businesslike in the immediate aftermath of this uncharacteristic joviality. “Just don’t let it interfere wit’cher content! We’re draggin’ ass enough as it is since that knucklehead loused up the deal with that McCleary broad.” The Chief muttered angrily for a moment before asking, “Whaddaya got there anyways?”

Berkman laid the paper on his desk and cracked his knuckles. “Just some paragraph I’m supposed to ‘edit’ into 2000 words,” he said, a little annoyed.

The Chief scoffed. “2000 words? You can do that in an iron lung! Hell, and standin’ on yer head to boot!”

Berkman agreed but sighed. “I know, it’s just… there’s just something that’s not setting right with me about it. It’s about…”

Another scoff. “‘About’ nothin’! Content is content. Bang it out and get back to work on yer pages! I need another 1400 by the weekend, sonny, come on,” he said pleadingly.

“It’s a ‘special edit,’” Berkman countered.

The Chief sighed, popped the rest of his smoke in his maw, swallowed and rolled his eyes. “Alright, so what’s it about, then?” he asked wearily and warily both.

“Oh, that guy Jacks—the ‘school’s for fools and tools’ guy,” Berkman said dismissively.

The Chief stood up from his perch on the corner of Berkman’s desk, fished with a pudgy, hairy-knuckled finger for a cigarette in his pack, then crushed the wrapped upon finding it empty and winged it in the nearby wastebasket. “Sounds like a waste’a paper to me,” he said tersely. “Buncha faggy poetry crap.”

“I don’t know, Chief, people seem…”

“Bah! People just need words on a page—don’t matter what the hell any of ‘em say,” the old man snarled as he stomped away. “Put yer backs into it, ya buncha nancies!” he shouted as he made his way out of the bullpen, the sound of the keys and typewriter bells intensifying thereafter.