In the early-1960s, when seven-year-olds like me were asked—almost every week—by mostly condescending adults what they wanted to be when they grew up, the answers were common. Boys ticked off fireman, cop, astronaut, teacher, baseball player, president, lifeguard, or whatever their fathers did. Given the era, girls were less forthcoming, but typical responses were stewardess, ballerina, actress, teacher, anything involved with horses, librarian, singer or restaurant cook. The more precocious opted for lawyer, scientist or symphony conductor. I would’ve killed, in retrospect, if a little girl said, unapologetically, high-priced escort, but c’mon, I’m just tickling my ribs here.

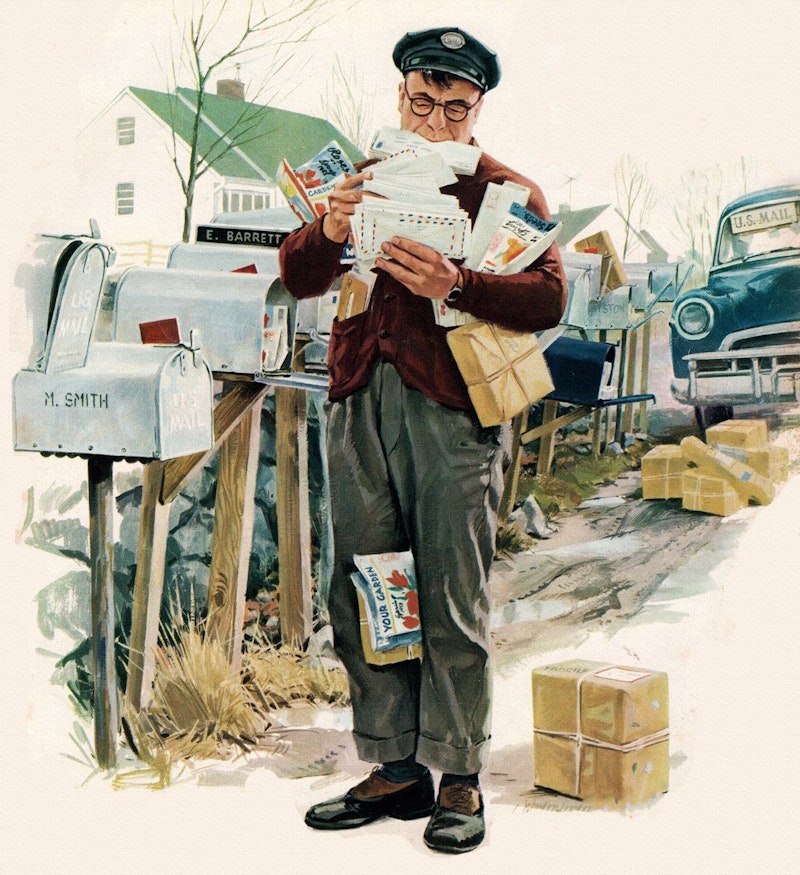

My own ambition in 1962, when I was seven, was unambiguous: I wanted to be a mailman. My parents, like so many Depression/WWII adults who desired a more prosperous life for their offspring, were mildly aghast at what they perceived as a modest goal, not out of snobbery but bewilderment. Pride and upward mobility permeated the thoughts of mom and dad: their five boys would go to the best colleges (with scholarships) and become lawyers, diplomats, authors or affluent businessmen. Anything prestigious and above their station, although the clergy was emphatically never promoted.

I loved everything associated with the United States Post Office. The bright mailboxes—seldom the object of graffiti or vandalism—emanated a whiff of patriotism on every corner in our Long Island town of Huntington. I went to the post office with my mom, as she sent off packages and purchased the latest sheets of commemorative stamps—at that time, a first-class letter cost four cents—and watched raptly as she attended to her small collection. Twice-a-day delivery was mostly phased out by then, except in certain areas, designated for special service for reasons unknown to me, and I can vaguely remember our house included in that (dare I say the word) privileged class.

Our mailman was a genial middle-aged fellow named John, and he walked his route without aid of a small truck. During the summer, I’d often wait at the bottom of our hill for him, and tag along on his rounds in our immediate neighborhood. I don’t think he minded, and was glad for the brief company, even if I was just a talkative kid wearing hand-me-downs that that were kind of ratty, since my mom wasn’t exactly a seamstress. Mom was very fond of John, and was generous with a tip at Christmas—which was unusual, since she was pretty tight-fisted and on a limited budget—mostly because he was weighed down with the prizes that she won from all the contests she entered. (From 1948-1967—sweepstakes took over then—she claimed over 1100 prizes, as I’ve noted before in this space.)

Zip Codes were introduced in 1963, and the USPS entered a new, exciting phase, although as I look back on the innovation—I couldn’t articulate it back then—some purity was lost, maybe an offshoot of the government’s space program and a preview of the 1964 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens, the same year Shea Stadium opened for the Mets. And a year older, I’d begun to read lots of daily newspapers, rudimentary biographies of presidents and athletes, and my plans of becoming a mailman were dashed in favor of a defense attorney or politician. (In 1965, reading the Village Voice, I was set on a journalism career, and that’s mostly panned out.) But receiving the mail every day was still a very big event, not only for Mom’s prizes, but the hundreds of Christmas cards, letters from my two oldest brothers, away at college—both took the time to correspond with the “little guys” at home, with really funny postcards and quips that cracked me up.

A few years later, around ’67, I was 12 and had a political button collection. Not satisfied with that, one summer I undertook the time-consuming task of writing to over 200 Senators, former Senators, members of Congress, mayors, even local councilmen—just totally whoring myself out—asking for campaign paraphernalia or autographs. Some never responded, but most had their staff forward pictures, maybe a bumper sticker or two, along with a standard note of “appreciation for your interest in democracy!” I remember that Jerry Ford, then a Michigan U.S. Representative, went above and beyond, and composed a fairly lengthy hand-written note, starting with “Dear Rusty, I was so excited to receive your letter”… and went on with some hocus-pocus (which was likely sincere) that wasn’t from an intern. Too much time on his hands? Maybe, but I appreciated it: and who’d have thought in 1967 that this modest man would one day become president.

A few years later, I had magazine subscriptions to Rolling Stone, National Lampoon, Sports Illustrated, The Sporting News, and Fusion, and if two of them appeared on the same day, man, my afternoon was made. It’s difficult for my kids to understand how important mail was to the country a long time ago, just as I can’t imagine the introduction of radio, mass-produced automobiles, or when chicken was more expensive than beef. Anyway, during my freshman year at college mail call at the dorm was a ritual; sometimes you’d strike out, other days brought three or four letters from high school friends (who’d spill the dirt on this or that person that we both knew) or relatives. It’s important to understand, too, that using the telephone was expensive for an out-of-town call. My friend Elena, who was off in France during junior year—while I was in Denver, working for College Press Service, and on the receiving end of books, records, obscure newspapers and letters from friends in Baltimore—wrote long, and richly-detailed letters about her experiences in Paris. That can’t be replicated in a text.

This continued at my weekly newspaper in Baltimore, City Paper, where it was just incredible the amount of freebies we received. On Saturdays, my partner at the paper, Alan Hirsch, and I would arrive at nine or so, and go to the Waverly post office for our bag of mail. The best part was seeing how much loot could be pilfered from the people who sent in personal ads to the paper: often we’d haul in $35, pocket the bills and leave the letters for our receptionist. It was an under-the-table perk.

In my mind, several events undermined the USPS: a number of work-related shootings at post offices in the mid-1980s and beyond led to the phrase, first coined in 1993, of “going postal.” It was a sour note. When the short-lived fax machine became a necessity at any business in the late-1980s, that had an effect on letters, although obviously the killer blow was email. It was an opportune time, in the 1990s, with the economy humming, for privatization of the USPS, but it never happened and now only a penny-foolish, pound-foolish billionaire would take it on.

The other day, my wife and I were in the car and I pointed out a USPS vehicle to her, and said, “An antique!” I haven’t the desire to delve into all current political folderol about election fraud, mail-in-ballots, and the feasibility of voting in person this November. I don’t trust any news outlet; don’t believe Trump and his acolytes or Nancy Pelosi and her own confederates. Like most Americans, I’d assume, I hope the upcoming election isn’t drawn out until Christmas or beyond. But just as I don’t count on mail arriving at my house Monday through Saturday, I take nothing for granted.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955