As the oldest surviving male relative, my father bore the duty of burying his Uncle Koppel. Koppel had survived three years in Nazi concentration camps and the misery of post-war Vienna. He came to America where he found success as a dentist. He never married, had no children and lived with his sister, also a survivor. In his 90s, after years of ill health, he finally succumbed.

My father made funeral arrangements with Koppel’s neighbor, a Hassidic rabbi. The rabbi assigned a Shomer, a “watchman,” to stay with the body until burial. Koppel had already paid for a plot and casket so the major details seemed to be handled.

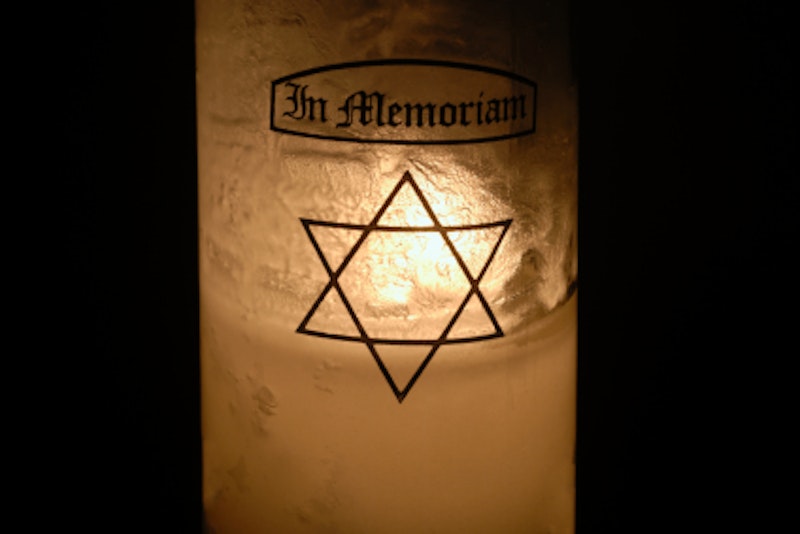

On the day of the funeral, my father and I drove to an Orthodox Jewish graveyard in East Los Angeles. The place had been around since the 1800s and the myriad headstones were carved with Hebrew letters and gilded Star of David’s. Graffiti covered the surrounding walls and the asphalt roads were crumbling.

We walked to the burial site and found a large mound of dirt beside an open grave. We watched as two Latino cemetery workers wheeled a pine wood coffin toward us. The coffin was thin and small without paint or adornment. The workers lifted the coffin onto the steel girders over the grave.

A white van wobbled over the battered road and stopped 20 feet away. The van door opened and an aging rabbi appeared followed by his well-dressed wife and young son. The rabbi had a white beard, black cloak, a yarmulke and a white tallit (prayer shawl). He also had what appeared to be scrambled egg remnants in his beard. The rabbi greeted my father while his wife and son stood nearby. He perused the surroundings. A sour look filled his face.

“Where are the mourners? We have no minyan.” He was referring to the quorum of 10 Jewish men required for an Orthodox funeral to be official. “I thought you took care of that,” my father said. “No, no, no.” The rabbi pointed to himself, his son, my father and me. “We need six more.”

“Can you call someone,” my father asked. “I have an appointment in 30 minutes. There’s no time.” My father began scratching his ear. He always did this when nervous. “Any ideas,” he asked me.

“Give me a minute,” I said. I walked to the cemetery office and found a Latino worker loading a pallet with sod. I reached into my wallet and pulled out 50 bucks. Five minutes later, six Latino gravediggers approached the gravesite. They all wore yarmulkes. The rabbi grimaced. “It’s the best we can do,” I said. The rabbi reluctantly opened his prayer book and began reading Kaddish (the mourner’s prayer). He directed one of the gravediggers to lower the coffin into the hole. He then told my father to toss a shovel full of dirt into the grave. I followed with a second shovel and the rabbi’s son added a third. The Latino gravediggers then took over. As the grave was being filled, the rabbi’s wife stepped forward and spoke to my father in German. The only words I understood were zweitausend dollar. My father scratched his ear and looked at the rabbi. The rabbi nodded in confirmation.

“What’s going on,” I asked.

“It’s nothing,” my father said.

“I heard something about $2000.”

“They’re asking me to contribute funds. So they can utter the daily prayers for Shiva.”

“You have to pay for them to pray?” The rabbi’s wife stepped forward. “It’s very important,” she said. “Prayers must be invoked three times a day for the next month so the soul can move toward Olam Ha-Ba.”

“That’s insane,” I said.

“It’s what’s required.”

“I’ll do it for 50 bucks, dad. Don’t you dare pay them $2000.”

“You’re not sanctified,” the rabbi’s wife said.

“How the hell do you know?”

The Latino gravediggers watched as we bickered. The grave was nearly filled. The rabbi reminded us he had another appointment. My father and the rabbi’s wife walked under a nearby tree. They conversed for a moment then returned to the grave.

“What happened,” I whispered to my dad. “I’ll tell you later.”

The rabbi said the El Malei Rachamim (the final prayer) and the burial was complete. My father and the rabbi shook hands then the rabbi and his family drove away. I thanked the Latino gravediggers and my father and I walked to our car.

“So how much they ding you for,” I asked.

“$500.”

“Unbelievable. Doesn’t that piss you off?”

“It’s how he makes his living. He has six kids, bills to pay, a mortgage. Every religion pays clergy for burial services. It’s normal.”

“Why do they have to do it at the gravesite?”

“It’s not considered proper for a rabbi to ask for money.”

“So his wife does it? That’s absurd.”

“Let it go,” my father said. “You sound petty.”

As we reached our car, I noticed a procession of mourners walking toward another gravesite. I counted 16 men. They had their minyan. I wondered if they’d already negotiated the prayer fee.