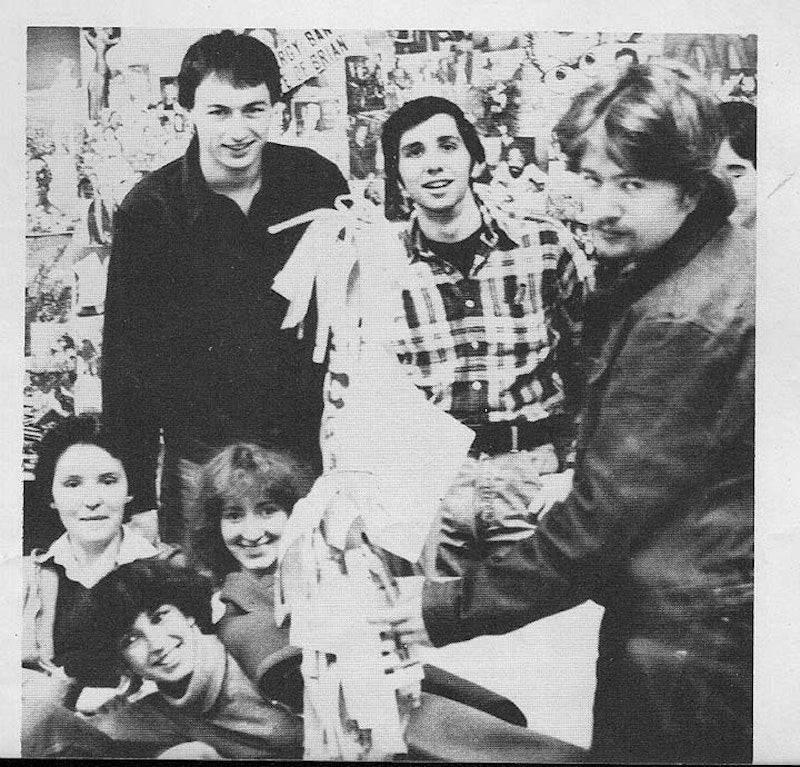

What have we got here? A photo of me (I’m on the right) with some of the staff of the St. Francis Collage newspaper, The Voice, which I edited in 1979 and 1980. I inherited the “editor’s chair” when everyone else on the editorial staff the previous year graduated. I learned newspaper editing and layout on the fly, and was sufficiently interested in points, picas and type fonts to carry me through an over 30-year career in the type business, as a proofreader, copy editor, typesetter, advertising copywriter and finally, a columnist and author. The career has effectively ended, since most of the low-end print production I was employed in had either been automated or moved overseas. Still, I scrabble around for what I can get, at my age.

In 1979, the landscape in New York City was completely different. There were rich and poor, but this had not become a “luxury city” yet and rich, poor and the “middle” mingled more readily. There were advantages and disadvantages. The city’s infrastructure was in deferred maintenance and subways were rolling, graffiti-scrawled fire hazards. The streetlamps didn’t get regular paint jobs and were routinely rusty. Entire neighborhoods had burned down because of looting and riots during and immediately following the big blackout of July 1977, the worst, socio-economically, of any of the major blackouts NYC had endured over the decades.

College was affordable then even for the lower middle class, which is where the old man and I found ourselves in 1979. I don’t think we paid over $30-35,000 for my entire tuition; I took five years to graduate because of those economics, when I went to work at various venues as my senior year(s) were wrapping up. To be frank, though, I had no business being in college in the first place.

I’m here in the center, holding my arm because it’s likely that Donna C., to my left, had just given me a rap on it to get me to smile a little. I could’ve auditioned for the Geico Caveman ads in that era; only lately have I been more diligent about shaving and haircuts, because I discovered I bear a resemblance to Steve Bannon, and don’t want to get tarred and feathered scrabbling around NYC like that.

I took the requisite courses and passed the tests, enough to graduate with a two-something index, but I was far from a dedicated student. Once I got to college, I had little interest in what was taught, or in business, medicine, law, or any other profession my classmates were sorting themselves into. I could read and write well and had a budding interest in NYC infrastructure, though only in its design elements, not its technical aspects. The very fact that college was affordable may have prevented me from entering trade school and becoming an electrician or plumber, jobs that are unionized and can’t be outsourced.

Then again, I had little interest in those jobs, either. I’ve always envied the old man, who went to work as a custodian at Stuyvesant Town and remained there, with little change in duties or standing, for 30 years (my idea of an ideal job is one where you have a stack of work in the morning inbox and they leave you alone to do it, which is far from the current office employment model of constant meetings, self-evaluations, and evaluations from superiors).

In those days I was not yet all-in on studying and writing about “forgotten” or little-known infrastructure or other aspects of New York. It’s too bad because Brooklyn Heights, where St. Francis is located, was the very first neighborhood to be landmarked by the new Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1965. I didn’t wander around much, confining myself to snooze or lunch breaks when I wasn’t in class. However, I must’ve evinced something of a spark because a girlfriend gave me a copy of Old Brooklyn Heights by Clay Lancaster on Dover Books, a compendium of all the historic buildings to be found in the neighborhood. I still have that book, which is weather-beaten and dog-eared today. Up until I moved to Queens in 1993 and, for a few years after, my chief way of getting around town was by bicycle. But as infrastructure mania kicked in, I couldn’t do it justice on a bicycle—I had to battle cars, pedestrians, dogs, and other bikes, and the safety margin was too thin to admire passing items of interest.

So, 20 years after college, I returned to Brooklyn Heights, this time shambling about the neighborhood—and many more of them—with a camera, shooting what I saw and reading and studying about what I saw after I got home.

Orange at Hicks St. is dominated by the 1849 Plymouth Church of the Pilgrims, where Henry Ward Beecher preached from the church’s opening until 1887. Beecher, a lecturer and writer as well as a pastor, attained a pre-eminence almost equal to Abraham Lincoln’s at the height of the Civil War, and even endorsed products, which well-known ministers did in the era. The pastor staged mock slave auctions to call attention to the evils of slavery; his sister, Harriet, wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Beecher is commemorated by two statues in Brooklyn Heights: one in Cadman Plaza that used to be closer to City (now Borough) Hall, and one in the garden court next to Plymouth Church, showing the preacher with Pinky, the most famous of his “auctioned slaves.” The church has been renovated in recent years and is worth a visit for services on Sundays.

Carbohydrate-conscious dieters will feel at home in Brooklyn Heights as a fruit salad of thoroughfares welcomes them. According to one story, a little old lady in tennis shoes is responsible for their names, a century and a half before little old ladies started wearing tennis shoes.

Before the IRT subway arrived in 1908, Brooklyn Heights was one of the more secluded areas in Brooklyn that only the very wealthy could afford. Jealousies and disputes arose among the moneyed gentry. The story goes, as recorded by the WPA Guide to New York, that in the decade prior to the Civil War, a local resident, whose name is given as Miss Middagh, resented her aristocratic neighbors and tore down the street signs bearing the names of the offending families and hastily installed signs bearing the names of her favorite fruit and trees, Pineapple, Orange, Cranberry and Willow. When Brooklyn city authorities restored the original street names, Miss Middagh struck again and changed them back. This tug-of-war eventually resolved itself in the lady’s favor with the streets retaining the plant names to this day.

The more likely story is that they were simply named by early-19th century landowners the Hicks Brothers, John and Jacob. Each brother bore the middle name Middagh; their mother’s maiden name. There is a Middagh St. and, of course, a Hicks St. in Brooklyn Heights. An 1816 map of Brooklyn Village compiled by Jeremiah Lott, as well as William Hooker’s Pocket Plan of 1827, show the three streets in question as Pineapple, Orange and Cranberry. It’s likely, therefore, that the amusing tale of Miss Middagh is apocryphal.

The three “fruit streets” are, for the most part, quiet and shady, with brick or brownstone town houses. Cranberry St., in particular, offers an iconic view of downtown Manhattan at its western end. Walt Whitman briefly lived on Cranberry as a child and Leaves of Grass was first printed in a now-demolished building at Fulton (now Cadman Plaza West) and Cranberry in 1855. The Cher vehicle Moonstruck also had scenes filmed at 19 Cranberry St. at the corner of Hicks.

Late at night, after drinking at O’Keefe’s on Court St. after school with friends, I’d have to negotiate the labyrinthine Borough Hall subway station, which serves both the 7th Ave. and Lexington Ave. IRT lines (2,3,4,5) as well as the BMT Broadway, which was still the RR when I was at SFC. Late in my college career I gained an appreciation for the station, with its spindly girders and terra cotta cartouches like this one, because it was undergoing a top-to-bottom restoration; the city began repairing its transit infrastructure in the early-1980s. This was originally a terminal when completed in the early 19-oughts, and then the Atlantic Ave. station served as the terminal before the IRT and BMT spread its initial flurry of construction further south in Brooklyn in the 1910s.

I came out of school knowing print techniques and with an appreciation for IRT terra cotta. I suppose that makes me more unique than I realized.

—Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens.