My American literature shelves had been in alphabetical order, but in bagging and boxing them before the guys delivering the couch arrived, I’d scrambled them as I only cleared off enough of the upper shelves and side spaces to make the cases movable. De-bagging, I pulled out some Cs, including Jacqueline Carey, Willa Cather and Kate Chopin, and encountered a narrow book of poems by Tom Clark. For at least 20 years I hadn’t looked at it. Its paperback cover reproduces a reverent painting by Clark that looks out from the first-base side stands of Fenway Park. Hand-drawn outlined letters in all caps float over the Green Monster.

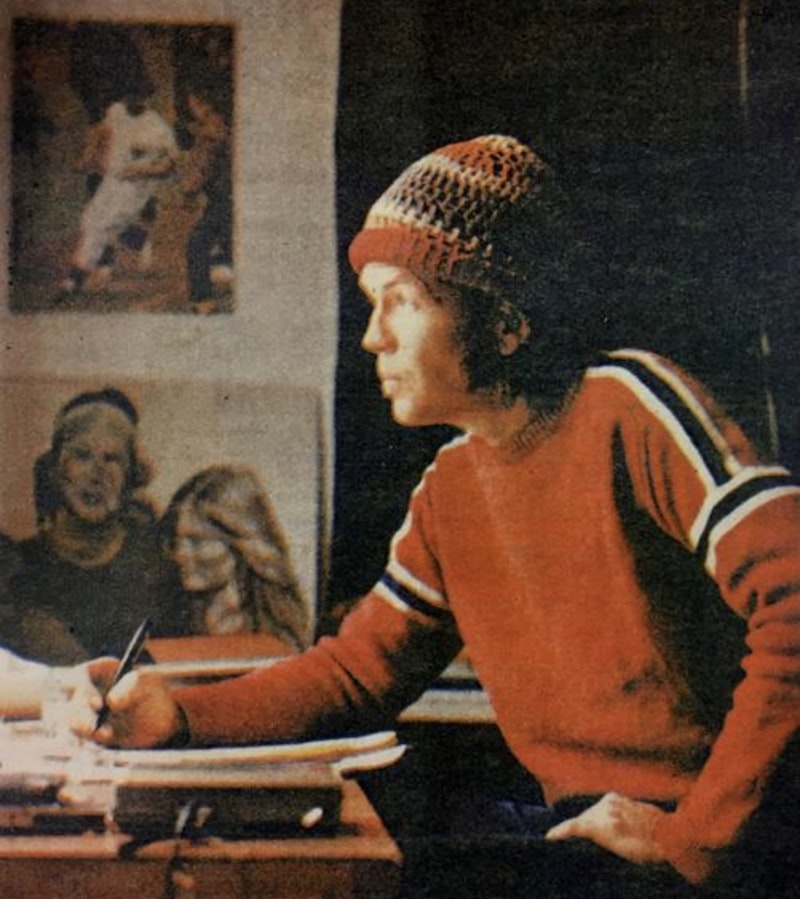

On the back cover is a photo of a smiling Tom Clark; sleeves rolled up, he wears a knit hat and is sitting next to a woman and a child in the sun in box seats at a baseball stadium. It could be in the stadium I knew best, San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. His preferred team as an adult were the Oakland A’s. Did I remember he had grown up in Chicago? I open the book. He had signed the title page of this 1976 North Atlantic Books edition. I didn’t ever meet him, so it must have been signed already when I bought it for $3 back in 1978 as a sophomore at UCSB, perhaps at the recommendation of my poetry teacher Robyn Bell. Amid the 64 pages are a dozen illustrations in pencil and charcoal, Clark’s own portraits of the ballplayers he addresses.

Maybe this has happened to you. You open a book from your formative literary years and you blink, and you realize, “I didn’t know I was copying … but this is what I was copying.” And by copying I mean completely unconsciously imitating.

The first poem, “The Baseball Connection,” is three lines long: “Baseball relates me to my own life/and to others like nothing else/ever has, not even English.”

Reading this for the first time in decades woke me up. It’s ridiculous but Clark’s introductory declaration was absolutely true for me until I was in my late-30s. I’m 62. Baseball was my childhood and writing about it was my teens, even after quitting the college team my freshman year. In my mid-20s, in grad school, I wrote a novel about a Steve Sax-like player, a Dodgers (and later Yankees) second-baseman who was very good until he was overwhelmed or cursed by an inability to throw the ball to first base. But my novel wasn’t about baseball, but a character my age who had a mysterious case of nerves and his relationship with a woman who had learning disabilities. I didn’t know then that the novel was about me.

Baseball meant so much to me. And I suppose, as Clark says, it was deeper than English. I haven’t played baseball in more than 40 years, but thanks to my older brother it was a first-language. A few weeks ago I had a dream where I’m on the field at try-outs and I realize I might be just slightly older than the other guys. I ask a coach who resembles Willie Randolph: “Is this for 18-year-olds or… can 19-year-olds play too?” As he mumbles an indecipherable answer I begin wondering how old I am—and wake up.

After piling all the displaced books back on the shelves, I went outside to a park bench to read Clark’s poems, all of which I took in as familiarly as the rooms of a childhood home. They stirred me more than Sappho’s, for whom at 24, to read in the original, I’d learned Greek; she was my patron saint of love poems. Hers I knew I was modeling my love poems on. Clark’s… I hadn’t understood until I reread Fan Poems that I was copying him, even when I wasn’t writing about baseball. Writing under the influence of others’ dazzling writing kept happening to me in undergraduate and early-graduate school years. My mentor, Professor Marvin Mudrick, would laugh at me in his office when I brought in my offerings: “Is this a parody?”

“Of what?”

“My god, it’s pure [Hemingway/Max Schott/D. H. Lawrence] through and through!”

I hadn’t noticed!

Here’s one of my favorite Clark poems:

“To Orestes Minoso”

Minnie, you collide

with Roberto Clemente

when I try to summon up

the greatest ballplayer I ever saw

I’m not talking about reputations

but what you did day in day out

was so much more than anyone had a right to expect

that no one except Bill Veeck

ever really understood it

You busted your ass every minute, like your heroic namesake

although I’m not too sure about that

since unfortunately I remember my Greek mythology

less well than I remember you

If you’d have been a white Protestant from

Maryland, you’d have been in movies and the Hall of Fame

and today instead of an obscure coach

you’d be a celebrity

drinking coffee on television

and flashing us your famous smile

in ads for athletes foot

Maybe it’s better this way.

Dazed but nostalgic by my discovery of a forgotten book that was still alive in me, I looked up “Tom+Clark, poet” on Google and discovered that he’d died in 2018 in Berkeley after getting hit by a car near his house. On Wikipedia I looked over the list of his books he’d crowed about to Kenny Holtzman. I’d read several of the ones published by 1980. I wondered if I still had his book of baseball tributes and paintings—another thin book—and in the living room I found where I’d shelved the tall volume, Baseball (Serendipity Books, Berkeley, 1976). Another treasure. He had signed this one too.

Here's my Tom Clark poem to Tom Clark:

“To Tom Clark”

You gave me back

my childhood

when I was 18

and didn’t even know

I wanted it back

then again

at 35

and (finally?) at 62

you make me not mind

not quite ever

growing up

or is it

growing beyond

baseball.