Dressed in tattered clothes, the gaunt faces had a dazed look that said it all. Crammed shoulder-to-shoulder in the railcar, they appeared practically dead. Plucked off the impoverished city streets, confused expressions proved how oblivious they were to the gravity of the situation. The impoverished children of the notorious “Orphan Trains” were ready for transport, off to a remote Midwest destination.

Problem was, despite the terms agreed on, some kids never made it to foster homes. Most ended up working indentured servitude on farms and in fields, as several states permitted. Some slept in sheds. Even babies were transported on Mercy Trains. Their names will never be remembered.

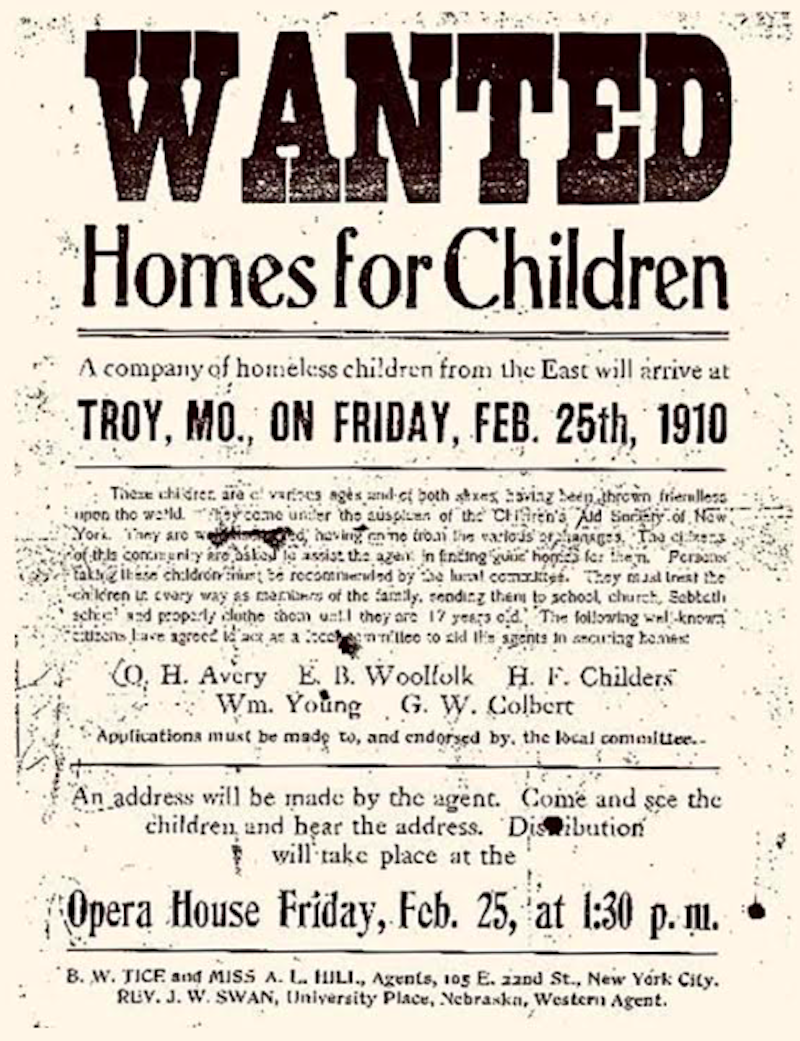

The 1910 poster hanging in the small town of Troy, Montana hawked the arrival of children arriving like a herd of new cattle. “These children are of various ages and of both sexes have been thrown friendless to the world.” Between 1854-1929 originating in New York under the auspices of The Children’s Aid Society, minister Charles Loring Brace organized a welfare program that marshaled vagrant street kids.

There was little control or vetting in the Orphan Train movement. From the 19th to the early-20th century, thousands of stolen lives were forced into labor with no legal standing. Public outcries for change went ignored until child welfare and legislation passed to combat the trains. It’s difficult to believe these Little Rascals were our Nation’s forefathers in a chapter of history that’s hardly discussed.

By the early-1900s, most Americans wanted to see child labor end and sought changes to adoption laws. The Keating-Owen Child Labor Act of 1916 was one of the first attempts to protect working children by prohibiting the sale of products made by firms employing children under the age of 14. It wasn’t until 1938, when Congress established the Fair Labor Standards Act, which made child labor illegal.

For some, being homeless was their only fault. With no role models, the hardened boys and girls led difficult lives on the streets of city slums. When their world closed in, they became victims of verbal abuse and denigration. Many were prone to reckless activity which resulted in crime, injury, and bloodshed.

The pointed finger of scorn set out to correct one thing: bad behavior. Another controversial way supposed to provide guidance to wayward youth appeared: Reform Schools (now known as boarding schools.) These were incarceration operations built so “incorrigible boys are committed at the request of their parents. Others are committed for misdemeanors and sundry offenses.” The thinking was separate facilities would prevent truants and illiterates from learning how to become a career criminal in adult prisons.

That didn’t happen. The reform school system provided the perfect opportunity to sweep the problem under the rug with devastating results. The shocking part was the widespread abuse and attacks by school custodians and the older kids. A growing number of problems festered in industrialized societies. On the cobblestone streets of England, beggars shined shoes surrounded by angry drunk adults. An underworld culture of homeless youth thrived; at times, they liked to wreak havoc. Consider the (1837-39) stories of Charles Dickens.

His name was Oliver Twist. He met the Artful Dodger Fagin, who in turn educated Twist and other homeless boys on the fine art of becoming swindlers and pickpockets. They pilfered apples and onions from market stalls, slipping them into their coat pockets. No one could expect this kind of farming could produce a such an extraordinary crop. To the cries of “Stop, Thief” the boys ran helter-skelter through London streets while dogs barked.

The US juvenile delinquency problem in the early-1800s drew the attention of fundamentalist social reformists. The Second Great Awakening involved religious revivals. These preacher-led social gatherings contributed to non-secular notions about our laws and institutions. The Bible events sounded like “the roar of Niagara Falls.” If teens were regulated, a fearful society’s nerves would settle down.

The first publicly-funded US reformatory (1846-1884) opened in Westborough, Massachusetts. There were 614 inmates by the 1850s. In 1859, the troubled boys burned half the school down. Despite all the institution’s problems, other states quickly followed suit. Charities and ministries opened their own private schools.

Treatment of teenagers was horrible. Inside the overcrowded institutions found filthy, squalid conditions, as well as poor food, resulting in a slew of health issues. Youth asylums punished teenagers using restrain and retrain methods. Because of the natural temptation to resist, runaway attempts and successful escapes were commonplace. Escapees who were recaptured were subjected to harsh corporal punishment from hanging kids by their thumbs to beatings and lashings. According to some, holes were drilled in wooden paddles for a better rear end slap. For years, the stigma of reform school’s painful past left an indelible mark, stoking fear in the hearts and minds of our country’s youth.

In Maryland, juvenile detention became a reality early on. The state adopted a statute in 1830 separating juveniles from adult criminals. Baltimore had a growing population of unruly youngsters. In order to give communities a sense of peace, The first House of Refuge opened on December 5th, 1855. The original Baltimore jail-like structure stood on a 55-acre hilltop near Gwynns Falls on Frederick Ave. It was renamed Maryland School for Boys and closed in 1911. Race and gender were separated in the reform facilities. In 1866, a female counterpart of the House of Refuge opened on Baker and Carey St., sheltering 583 women.

Even so, issues persisted, and efforts failed. During the Progressive Era (1890-1913) people began to see things differently. A call for change was promoted by activists, muckrakers, and reformers alike. Local initiatives were followed by national endeavors. The emphasis shifted to educational reform and instruction. Maryland and other progressive states gained control of their adolescent affairs through of juvenile service departments. Now a variety of facilities fulfill the requirements of young people, including professional counseling, medical services, and residential treatment center operations.

There’s a caveat, if you’re seeking rehab help online nowadays, it’s a frustrating experience. One finds a plethora of drug recovery services promoting mixed messages: “It is the right decision. We offer a gold standard for a brighter tomorrow.” Scroll down for a slideshow of saltwater tropical fish and a photo of a steak claiming “culinary dining experience. Call now!” There are other disadvantages too: what sort of PTSD situation are you going to create by imprisoning a child for 10 months in a Montana mountain detention facility.

It’s a problem with no clear answers. A variety of elements influence success based on one’s precise needs. When time is of the essence, the road to recovery is only the first step. The eventual outcome will hopefully be more positive than the Orphan Trains’ forgotten youngsters. That is a story worth telling.